China’s Latest Cynical Buzzword Is a Cry for Help

If you’re young, highly educated, and unable to find a satisfying job, China has the buzzword — or buzzwords — for you. Perhaps you’re quiet quitting by “lying flat” or adopting a “Buddhist-like” attitude to life’s tribulations. Or maybe you’re catching the latest fad and adding your story to the stack of “Kong Yiji literature” that has swept across Chinese social media in recent weeks.

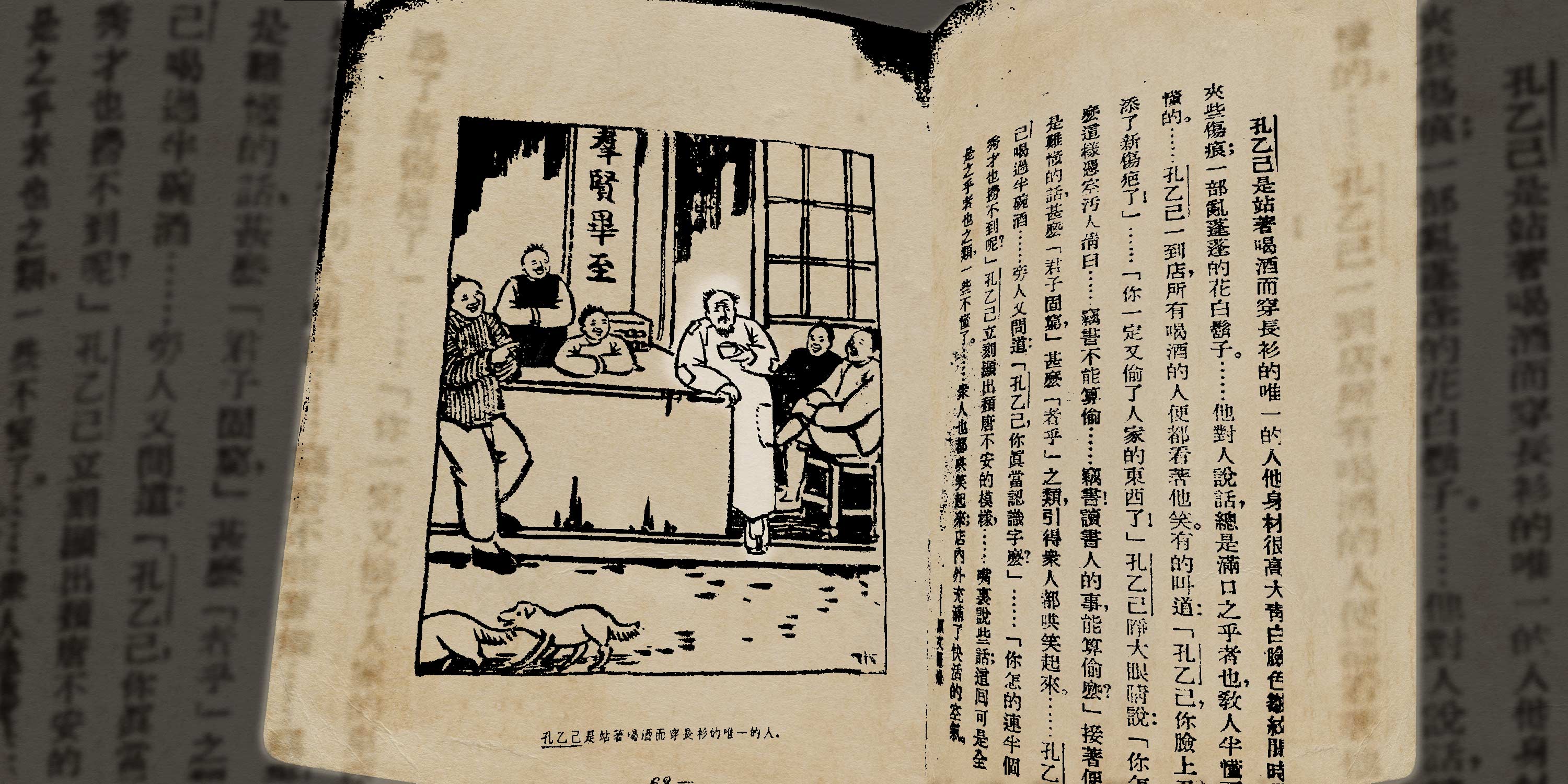

A character created by the author and cultural critic Lu Xun in 1919, Chinese schoolchildren learn that Kong Yiji was a pedantic man of letters who stubbornly clung to tradition and failed to adapt to the times. Now, many young Chinese, struggling to find a good job despite their degrees, have come to feel a certain kinship with him. Contrary to what they’d been led to believe, not only has higher education not translated into professional success, but it’s even become a burden — much like the battered scholar’s robes that make Kong Yiji the subject of derision in Lu Xun’s story.

They’re hardly the first generation to feel this way. “Kong Yiji literature” is the latest iteration of a 40-year-old debate over the value of an education in China. Even in the years after the Cultural Revolution came to an end and the gaokao college entrance exam was restored — typically considered a cultural “golden age” — the emergence of a market economy disillusioned many intellectuals, leading to popular sayings like, “You’d be better off selling tea eggs than designing atomic bombs.” Though somewhat hyperbolic, the phrase nevertheless captures the era’s widespread dissatisfaction at the disjuncture between wealth and social status on the one hand and academic pedigree on the other.

During my own university studies in the early 2000s, it was common to see people on campus reading inspirational self-help books about the “road to success.” We gradually realized that, after the expansion of higher education in the 1990s, passing the gaokao might no longer be a guarantee of a bright future, and that we’d have to work harder than those before us to realize our goals. Nevertheless, there was a stubborn optimism about the future: We believed in our capacity to change our fate.

At the time, China was in the middle of a sustained period of rapid growth. It had just joined the World Trade Organization, and new employment and business opportunities eventually helped the job market accommodate the growing number of university graduates. An extreme example of this trajectory is the Peking University student Lu Buxuan. After graduating from one of China’s best universities in the early 2000s, Lu decided to sell pork to make ends meet, a decision that earned him widespread media coverage as a cautionary tale — proof of the declining value of a college degree. A decade later, however, he’d become an executive at his own foodstuff company.

The buzzword-industrial complex picked up steam after the advent of social media, as digital natives created new online slang to express their feelings of anxiety and loss of control. In the early 2010s, diaosi, originally a vulgar term for pubic hair, took social media by storm as a way for young people to evoke their sense of inadequacy in the face of rising house prices and dwindling wages. Looking back, these fears were largely unwarranted, as that generation graduated in time to benefit from the explosive growth of the internet industry and the emergence of venture capital.

Subsequent university classes haven’t been quite as lucky, at least so far. As economic growth slows and past drivers of growth like the tech industry wobble, the road to success has grown murkier — and the language of internet users more cynical. In the past five years, young people have bemoaned the “involution” of China’s rat race, the alienation of “small-town exam experts” for whom admittance into a top university becomes a lesson in humiliation, and the desire to stop working and lie flat.

While complaints about “involution” and overwork are more common among those with experience in the workplace, the sense of disillusionment has already set in for undergrad and grad school students. Because of prolonged COVID-19 lockdowns, many of them completed a significant chunk of their degree online and therefore lack the internship and life experiences of previous cohorts. As a result, they feel like fish out of water at recruitment events. Some even experience discrimination, with many employers saying they aren’t interested in graduates who spent their college careers learning remotely.

The sentiment that degrees have lost their value is particularly strong among humanities and social science majors. Even finance and economics majors have lost their luster, reflecting a growing pessimism regarding the employment prospects for new grads in the face of slowing economic growth, industry uncertainty, and the U.S.-China trade war. Although STEM majors remain in high demand, for other students, university life is tinged with melancholy: From decreased admissions cutoffs to skeptical recruiters, they’re consistently made to feel that society holds them in low esteem, which in turn causes them to doubt their own value and future.

The reaction to these fears suggests a growing chasm between generations. Although media commentaries have generally recognized the various difficulties young people face, they often criticize “Kong Yiji literature” while optimistically exhorting young Chinese to “carry out creative experiments that put their unique strengths into play.”

There’s a certain amount of truth to this statement, but these “Chicken Soup for the Soul”-style pieces place the onus on individuals to overcome what are essentially societal problems and ring hollow to many young Chinese. Young people are unwilling to accept lectures from a generation who benefited from a wider range of opportunities and smoother professional trajectories. What they want isn’t condescending advice, but empathy and greater acknowledgement of the problems plaguing the job market and workplace.

If anything, we should be grateful for the popularity of Kong Yiji: The current wave of discontent goes to show that people haven’t completely lost hope in the future. The real problems come when young people silently resign themselves to a lack of opportunity and social mobility, rather than calling for change. The cynical response would be to suggest relatively safe and stable alternatives, such as taking the civil service exam or applying to state-owned companies. But not only would this quash young people’s will to change society, it’s also a convenient way for those of us who benefited from China’s rapid growth to shirk our responsibility — that is, to provide future generations with a stable yet vibrant economy that respects expertise, encourages innovation, and permits mistakes.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Cai Yineng and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: An illustration for Lu Xun’s short story “Kong Yiji,” visuals from @秋水书店 on Kongfz.com, reedited by Sixth Tone)