What China’s Gate Debate Says About Trust

Nowa Huta was an unexpected stop on our summer trip to Poland in 2012. We were in Krakow and a local art student suggested we visit the Soviet-era 1950s settlement. Departing from the city’s historical center — a marvel of Polish Renaissance architecture and ornate streets — I was astonished when we reached Nowa Huta, Krakow’s easternmost district.

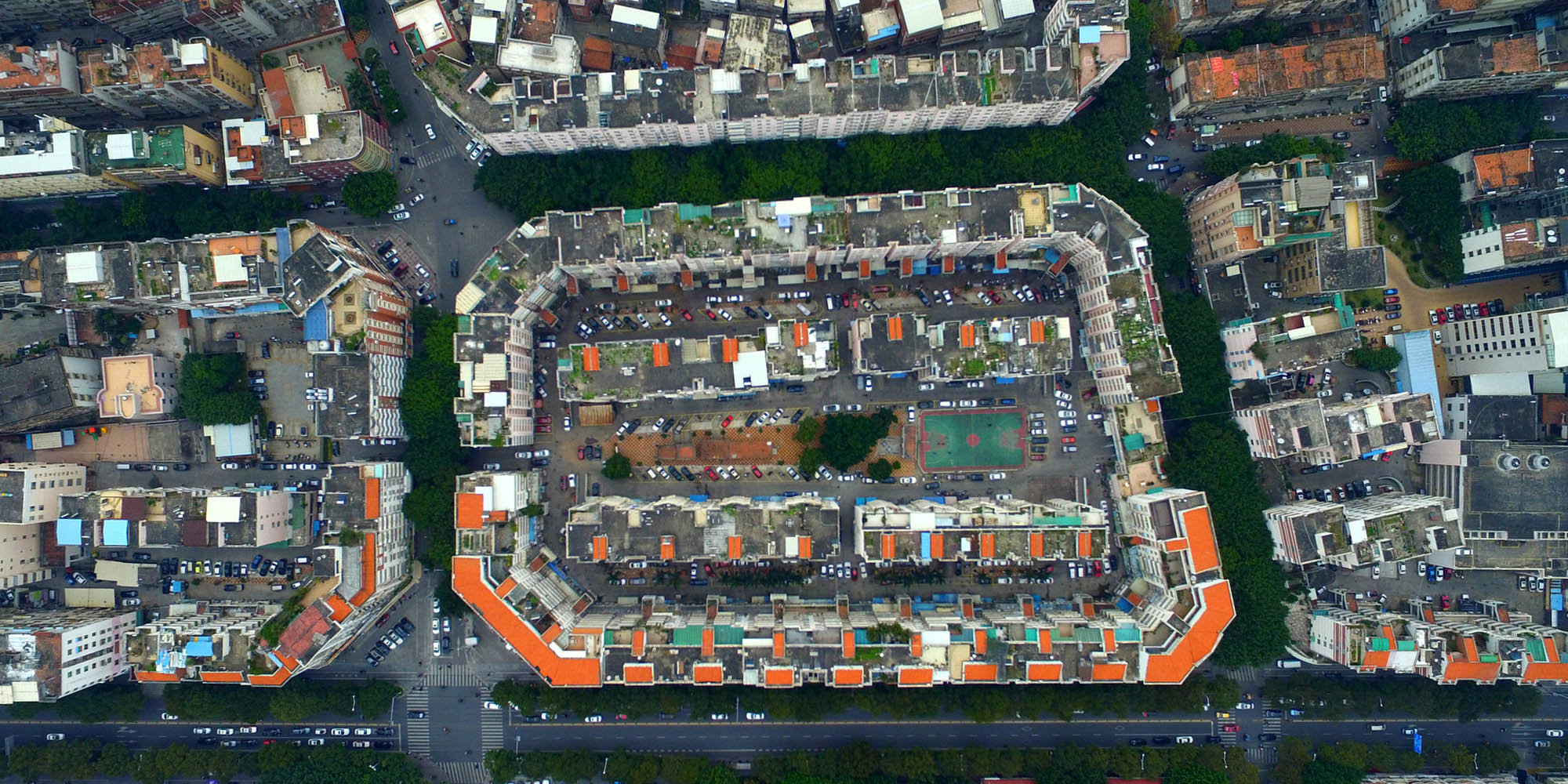

The avenues were plain and wide, ending in barren town squares. Superblocks were enclosed by fences and high walls seemed to surround me wherever I turned. The entire area was quietly powerful. According to my guide, the layout assured the district could quickly transform into a defensive fortress in the event of a military attack.

At the time I assumed I was drawn to it for its novelty; it wasn’t until later that I realized why the district resounded so deeply in me.

Born in the late 1980s, I have only vague memories of the work units, or danwei, that began sprouting up after China became a socialist republic in 1949. These collective units spent most of their time together, both in work and in leisure. This idea was taken from the Soviets, who pursued a similar vein of mass-collectivization in the mid-20th century.

The development of China’s contemporary gated communities began with the planned economy in the 1950s. Since people began working in collective groups in specific industries, it made sense to keep them living together, so the government began building large compounds with guards posted at the entry. These communities normally functioned independently of one another — each had their own set of facilities for residents. People quickly became used to living like this.

Although work units still exist, they have been in steady decline since Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms beginning in the 1980s and the expansion of the private sector in the 1990s, which provided more employment opportunities. At the same time, the Chinese real estate market also took off. A reform in 1998 separated housing from employment and completely opened the property market to the public for the first time since 1949.

[node:field_quote]

Finally, there was no longer a need for gated communities. And yet, the real estate market continued developing property in this way, whether they be luxury condos or housing for factory workers.

But these walled compounds have recently come under attack by China’s State Council, who in March released a new set of guidelines for urban planning and development. The new agenda prioritizes mixed-use development and urban public spaces, demanding gated communities open up and allow in outside traffic.

Known in Chinese as the “open blocks” initiative, the guidelines were immediately met with fierce criticism online. Public safety was the most voiced concern, followed by traffic accidents and theft. Fences and guards are considered the prime means of lowering crime rates. Violations of property law were also cited by many protestors, as it is understood in China that home buyers pay for both floor area and shared public area.

The list of grievances goes on. However, the deepest reason for the distress lies in the mindset of the Chinese people. We prefer enclosure because it’s what we’re used to. The craving for security, collective communities, and privacy remains incredibly prevalent in the Chinese mindset.

Unfortunately, as China’s economy expands and the income gap widens, urban spatial segregation becomes more discernible than ever. In 2015, the Gini coefficient — a measure of income inequality scaled from zero to one where zero represents complete equality — reached 0.462 in China.

Not only has residence inside a gated community long been deemed desirable as an indicator of wealth and status, it also offers people the opportunity to live with neighbors of a similar financial class.

In 2006, China’s largest real estate developer Vanke proposed a bold experiment. They wanted to attempt a social housing project by building affordable apartments inside a deluxe seaside community in Shenzhen. However, a news leak provoked protest from the villa owners of the target development and the company had to relocate the project to suburban Guangzhou.

Once relocated, the architecture firm contracted by Vanke designed a space with contemporary aesthetics and dynamic spaces. But it was still rejected by the adjacent community, who were wary of the kind of people not able to afford luxury housing. A fence was eventually built to reassure the neighbors that their low-income neighbors wouldn’t hang around their gardens and pools.

But not everyone is unhappy with the State Council’s new guidelines. Urban planning and design professionals argue that opening up the many gigantic gated communities, which often stretch for blocks, will decrease traffic congestion.

An increase in the efficient use of public space is another upside, as enclosures and lack of street life render large sections of Chinese cities muted, stagnant, and far from the pedestrian-friendly walks idealized by urban studies author Jane Jacobs.

Another more visible but less talked about consequence of gated communities are the many instances of mismatched urban design. The layout of China’s residential districts are constructed around isolated walled-off blocks, whose architecture takes on a degree of randomness, employing everything from Mediterranean balconies to traditional Chinese detailing. It is difficult for architects to relate to buildings out of sight since the communities are kept closed off from one another, and thus matching styles are often nonexistent.

China now faces a battle of urban welfare versus personal interest. But is it even necessary to wage such a war? Since for the moment walls remain standing, we can perhaps act on a different level. Can we instead build confidence and trust in a country that gradually comes to require less walled-up protection? Will a collective sense of identity and charity arise through other means?

The new urbanization guidelines play in with global trends of ecological development and ideals of localism. But in the case of China, encouraging openness and diversity is perhaps a better approach than forcibly tearing down walls.

(Header image: An aerial view of a gated community in Quanzhou, Fujian province, Feb. 22, 2016. VCG)