How Flooding Turned a Bustling Town into a Backwater

This is the first in a series of articles about a town struggling to survive in a flood zone along the Yangtze River.

Nearly two decades after a flood killed thousands in central China’s Hubei province, the constant fear of another disaster has left Paizhouwan Township only half alive. Of the more than 100 businesses that once flourished in the town, just 10 or so are left, swaying precariously on their last legs. Around 55,000 people are registered as residents, but more than half of them have sought employment elsewhere. Shop signs bearing slogans from the ’70s are caked in a thick layer of dust.

A bustling shipping town for more than 1,000 years, Paizhouwan has seen its fortunes ebb and flow along with the Yangtze River upon which it sits. Located near major cities like provincial capital Wuhan, it was once the jewel in Jiayu County’s crown. But the ’80s brought hard times for the shipping industry, while annual flooding shook the town’s economy and drove many residents to seek higher ground. Eighteen years after one of the most devastating floods in modern memory, Paizhouwan’s fortunes have become tied up in the political struggle to manage the ever-present risk of flooding in the areas surrounding China’s longest river.

When the 1998 flood hit, an embankment protected most of the area around Paizhouwan — but in the town itself, the levee broke when the river level reached 31 meters. Floodwater flushed in, reaching as high as the ceilings of ground-floor rooms, and residents climbed trees and utility poles to keep from being swept away. Those who survived were evacuated the following day and lived in emergency tents as internally displaced people.

After the disaster, the levee was rebuilt and is now, once again, vital to Paizhouwan’s flood defense. Preventing a catastrophe like that of 1998 is imperative, so outlet gates have been built atop the embankments to contain floodwater. But the threat of destruction remains: Paizhouwan was formally designated a detention storage area, meaning that if there is danger of severe flooding in the surrounding area, Paizhouwan’s sluices must be opened and the town sacrificed to minimize damage to the region. Over the years, this devastating possibility — combined with the decline of the shipping industry — has turned Paizhouwan from a flourishing port town to the most underdeveloped township in the whole county.

Residents like Wang Shiyan, the retired former secretary and director of the Hualong Ceramics Factory in Paizhouwan, have witnessed the town’s shifting fortunes. Wang turns 85 this year, but he still has clear memories of the era before the Chinese Communist Party took power in 1949. Back then, Paizhouwan was a bustling city with a well-established shipping industry. Wang’s father set up a stall on People’s Street, just outside the family’s front door, where he fashioned handicrafts out of willow. The family’s life was quite comfortable.

But at the end of the 1950s, People’s Street was inundated when the river rose and flushed away its banks. “Every year, a few hundred meters of riverbank would be destroyed,” Wang said. With the constant threat of flooding, Paizhouwan’s economy became weaker by the day.

From 1962 to 1985, the state contributed subsidies amounting to 1.57 million yuan ($226,000), while localities themselves supplied a further 1.37 million yuan. The money was put into 256,000 cubic meters of support wall, which gradually brought the flood threat under control. The street outside Wang’s front door became an embankment.

Following the reform and opening-up policy enacted in 1978, with the riverbank well-protected, Paizhouwan’s economy bounced back — primarily thanks to its favorable position on one of China’s major waterways. Township enterprises developed rapidly, and when Wang took up his post at the ceramics factory in 1980, there were over 1,200 workers there, laboring in shifts around the clock. Tons of tile waited at the wharf to be loaded and ferried downstream to Shanghai and the southern city of Guangzhou, and some were brought as far as Southeast Asia.

When Wang talks about the past, a note of pride comes through in his voice. The room he lives in is filled with old certificates and photographs, all polished to a gleam.

“Until I retired in 1993, Hualong was always the best- or second best-performing enterprise in Jiayu County. We made more than 2 million yuan each year for the country’s tax collectors alone,” he said.

When Paizhouwan was flourishing, more and more people moved to the town, hoping for a better life for themselves and their children. One of them was Yang Chenglin, who began working at a rubber factory. “I didn’t want to remain a country peasant, nor did I want that for my children,” Yang said. He hoped his children would follow him into the factory once they grew up.

But the promise of fortune wasn’t meant to last. Less than two years after Yang moved to Paizhouwan, the rubber factory where he worked was facing bankruptcy.

In fact, the decline began in the latter half of the 1980s, when the water transportation industry started to fall into the red. First came the official closure of Paizhouwan’s passenger ferry dock. Next, the branch of the county-wide company in charge of freight shipping began reporting losses. Growing competition in the river transportation market jacked up the cost of labor, until the local branch announced bankruptcy in 1997. With the country’s overland transportation network developing rapidly, shipping hubs like Paizhouwan saw their once-strategic riverside positions rendered worthless.

Township enterprises began to dry up, and Paizhouwan’s ceramics and rubber factories were no exception. In 1995, Hualong experienced operational difficulties, to which it responded by halting production and laying off workers. Several hundred employees were dismissed without compensation and left to scrounge around for odd jobs; locals took to calling them “wandering ghosts.”

Then came the Yangtze floods of 1998, which former ceramics factory director Wang considers an act of God that sealed Hualong’s fate. According to figures from the Chinese Ministry of Water Resources, the flooding that ravaged the entire Yangtze alluvial plain destroyed 207 million mu (138,000 square kilometers) of agricultural land, resulted in the deaths of 4,150 people, and demolished 6.85 million houses. The direct economic losses of the flood stood at 255.1 billion yuan.

In 2000, a brick and tile merchant named Wang Jianghe — of no relation to Wang Shiyan — moved from eastern China’s Fujian province to Paizhouwan with his wife. Attracted by the strong factory infrastructure in the town, he bought the old Hualong ceramics plant. At first, enough orders came in for the business to survive, but he soon began to struggle. The population was stagnating, the market was underdeveloped, and after shipping was abandoned, the cost of overland haulage was higher than elsewhere.

To give his factory a competitive advantage, each brick or tile would have to be 0.01 yuan cheaper than those produced by other factories, Wang Jianghe calculated. “For a factory like ours, which distributes such a large quantity of goods, that 0.01 yuan was often fatal,” he said. From 2015 onward, orders began to dwindle, to the point where the factory only opened for a single month this year. Wang Jianghe has already started planning to leave Paizhouwan and find work somewhere else.

However, a glimmer of hope remains. Wang Jianghe’s wife said she recently heard that Paizhouwan might be merged with the municipality of Wuhan. If they merged, Paizhouwan’s embankment could be raised from its current status as a private embankment to that of a state embankment.

“If the Paizhouwan embankment can be upgraded to the national level, our factory will increase in value several times over,” she said. But having lived in Paizhouwan for 16 years, the couple have lost count of how many times they’ve heard such news before and how many times they have raised their hopes, only to see them dashed.

“Flood protection has always been a source of competition among different areas,” said Liang Deming, a retired engineer who worked on the Paizhouwan section of the embankment. After the 1998 disaster, the government of central China’s Hunan province, south of Hubei, signaled repeatedly that it would be willing to take on the costs necessary to “straighten out” the meander in the river on which Paizhouwan sits and turn it into a flood zone. Residents would be moved to a better-protected public embankment area — all at the expense of another provincial government.

For Hunan, this would mean that the river would no longer be slowed down by the meander, easing the risk of flooding. But for Wuhan, the 10 million-person capital of Hubei just downstream from Paizhouwan, straightening the river would allow floodwater to rush through more quickly, increasing the flood risk for the area. In the politics of flood defense, Paizhouwan had become a pawn.

In 2003, after extensive research, the national Changjiang Water Resources Commission declared the straightening-out project to be unworkable, leaving the proposal dead in the water. But in 2010, Zhou Jianjun, a professor at Beijing’s Tsinghua University and head of a hydro-science research team supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, presented evidence that showed the plan was feasible after all. He suggested a compromise whereby a newly built sluice gate would be kept shut most of the time and only opened when it was absolutely necessary. However, his plan has never been considered, Zhou said. “It hasn’t been discussed. The commission and the water conservancy department basically don’t listen to anyone else’s advice,” he said.

Paizhouwan resident Yang, who gave up his family’s fertile fields to move to the town, has become a running joke among his fellow villagers. Whenever he is out and about, people tease him: “Mr. Yang, you’ve thrown away your fortune!” Now unemployed, Yang’s eldest son sits at home “doing a bit of this and that.” His younger son works as a welder in a coastal city several hours from his hometown, while his daughter married into a rural family in the nearby city of Honghu “because there’s a lot of land out that way, and it’s developing much better than Paizhouwan,” he said. After leaving his post at the rubber factory, Yang caught fish and chopped firewood for a time. Now over 70 and missing most of his teeth, he still intends to go looking for work in Wuhan as a cement mixer.

Yang is one of the town’s “wandering ghosts,” and yet, when the risk of flooding arises like it did this past summer, he still gets a call from the local cadre to help reinforce the embankment.

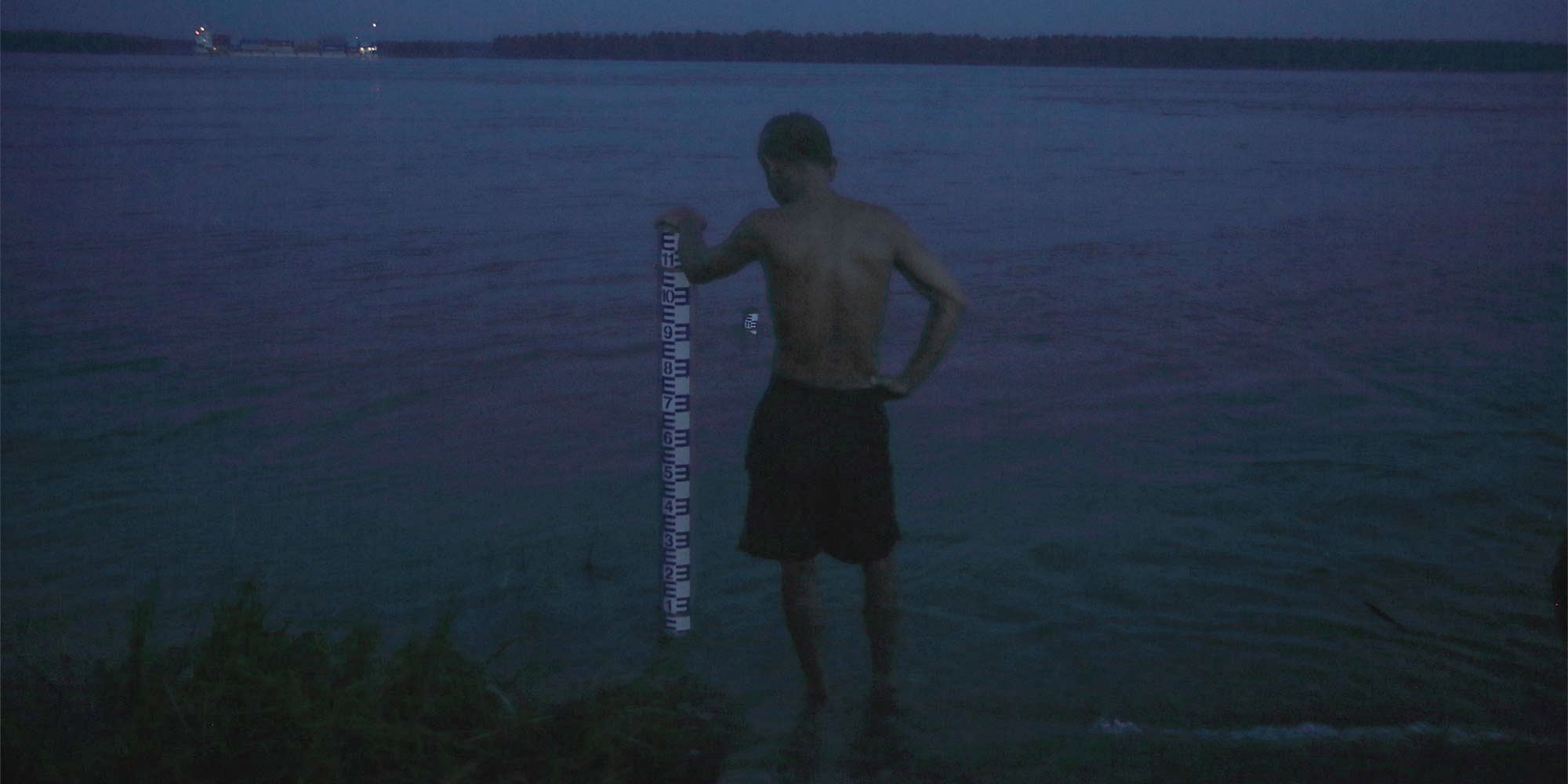

(Header image: A resident measures the water level outside the embankment in Paizhouwan Township, Hubei province, July 26, 2016. Zhou Pinglang/Sixth Tone)