How ‘Blood-Sweating Horses’ Became Auspicious Symbols in China

According to the traditional Chinese zodiac, this year marks the Year of the Horse, the seventh animal in the 12-year cycle. Thanks to their usefulness throughout history — domesticated in ancient times for transportation and later indispensable for carrying mounted forces in warfare — horses have come to symbolize various positive qualities such as success and progress in China.

However, one specific breed long stood out from the herd: the so-called blood-sweating horse. Known as Tianma, or the “Heavenly Horse,” this mythical being was celebrated and revered for its exceptional endurance, and was named for the blood said to secrete from its shoulders when running.

During the Western Han dynasty (206 BC–AD 25), “The Book of Later Han” recounts that Emperor Wu dispatched an army to attack the state of Dayuan in the Western Regions (now the Ferghana Valley in Central Asia) to obtain the “blood-sweating horses” found there. Some researchers believe this was a real condition affecting the region’s horses caused by blood-sucking parasites; others hypothesize that the horses were chestnut-colored and that when they perspired, their coats would become wet with sweat, creating the illusion of bleeding.

Upon hearing of these famed steeds, the Song-dynasty (960–1279) historian and statesman Sima Guang composed a poem titled “Song of the Heavenly Horse,” in which he wrote: “In ancient times, all knew of Dayuan’s blood-sweating horses / Yet the dragon-breed from Qinghai has even more remarkable bones / I once saw them depicted in old paintings on silk / Never did I expect to see one in the human world today.”

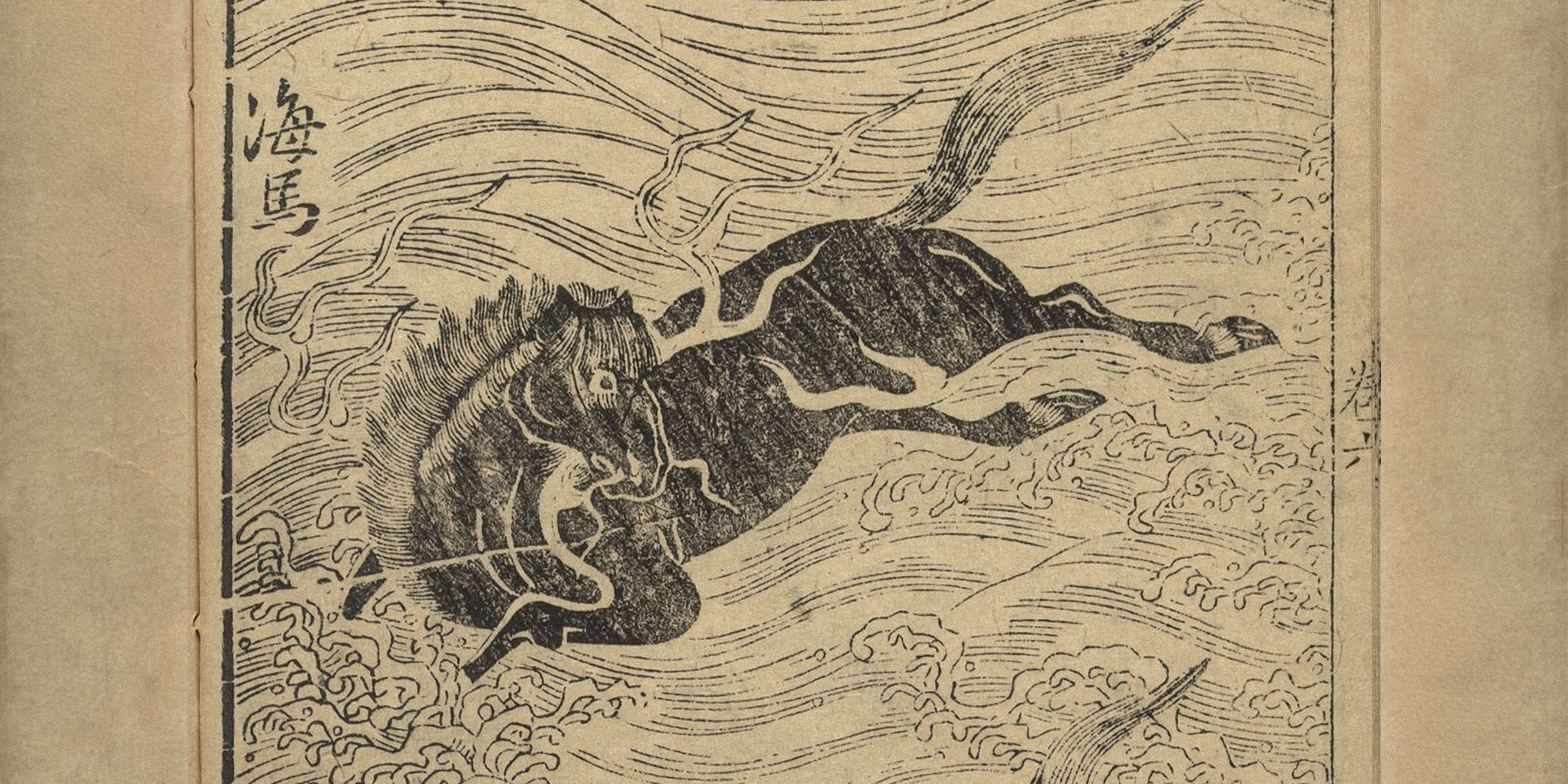

A precursor to the Tianma may have taken shape in early frontier legends associated with the northwestern regions of what is now Qinghai province. Later dynastic histories, including “The Book of Sui,” describe peoples living around Qinghai Lake as accomplished horse breeders and recount tales of extraordinary steeds said to travel one thousand li — roughly 500 kilometers — in a single day. Some accounts further link these horses to a dragon-like creature said to emerge from the lake, which was often referred to as a “sea,” giving rise to imagery associated with the Haima (“Sea Horse”) and Longma (“Dragon Steed”). Even earlier, the mythological compilation “Classic of Mountains and Seas” mentions a horse-like beast dwelling in the “Northern Sea,” named Taotu, suggesting that such fabled equines occupied the Chinese imagination long before they became attached to specific historical peoples or places.

“Haima” can also be interpreted as the “horse from overseas.” The “Administrative Map of the Nine Districts,” published during the Xuanhe period of the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127), depicts a Haima in what is now the South China Sea.

Meanwhile, the “Records of Yi Jian” compiled by Southern Song-dynasty (1127–1279) statesman Hong Mai features a story titled “Haima.” In it, a similar creature — complete with a red mane and hooves — is described as having suddenly surfaced one night in Shanggongwan, a coastal settlement near the southern city of Guangzhou. The creature then charged into the villagers’ homes, killing livestock and leaving traces of blood-like sweat. The locals then banded together to kill it, and just before dawn the next day, the sound of thousands of troops filled the air, promising to kill the ferocious equine. Seeing this as a bad omen, some villagers quickly fled. The next day, the Haima exacted its revenge, drowning more than a hundred families. This is a rare story in which the Haima, originally considered an auspicious creature, takes on a more monstrous character.

From the blood-sweating horses of Dayuan to the steeds descended from the dragons of Qinghai Lake, the horse’s legend became increasingly extraordinary, eventually evolving into a kind of fantastical creature. Following its transformation, the Haima was often utilized as an auspicious motif. One such example is a bronze statue unearthed in Wuwei, in the northwestern Gansu province, known as the “Galloping Horse Treading on a Flying Swallow.” The Han-dynasty sculpture is a manifestation of the horse-riding customs of the time, offering a glimpse into the majestic aura with which such animals were imbued.

From the Yuan (1279–1368) to the Qing dynasties (1644–1911), galloping horses were a common auspicious motif used to decorate porcelain wares. Artisans depicted the creature leaping over billowing waves, hooves raised high and manes flying behind, exuding a remarkable vitality. They were also portrayed with two red flames above their shoulders, perhaps echoing the crimson blood of their blood-sweating forefathers.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, Haima motifs appeared on the ceremonial robes worn by court officials. The animal can also be spotted among the mythical creatures adorned on the roof ridges of ancient buildings, serving to connect heaven and earth. According to the Qing’s comprehensive legal and administrative canon “Collected Statutes of the Qing Dynasty,” the order of the ridge beasts was: dragon, phoenix, lion, Tianma, Haima, Suanni, Yayu, Xiezhi, Douniu, and Hangshi. The placement of the Haima and Tianma alongside one another reflects their close connection, and their aesthetic similarities meant that their names were often used interchangeably.

The Tianma and Haima likely originated in the fine horse breeds of Central Asia. Over time, however, they drifted from reality to legend, gradually shedding their earthly traits to become auspicious mythical beings. Before the advent of modern modes of transportation, animals from distant lands often took on extraordinary or supernatural qualities, their reputations magnified by the vast distances their stories traveled. Through this process of mythologization, they were transformed into symbols of power and good fortune — the Haima and Tianma stand as enduring testaments to that evolution.