What’s In a Name? How Kalgan Transformed From Gate, to City, to Planet

In his 1952 science fiction novel “Foundation and Empire,” Isaac Asimov introduced a fictional planet named “Kalgan” as an ideal holiday destination: “How about a better one on Kalgan? It’s [sic] semitropical — beaches, water sports, bird hunting — quite the vacation spot. It’s about seven thousand parsecs in — not too far.”

It remains unclear where Asimov drew his inspiration for the planet itself, but surprisingly, there is a “Kalgan” on Earth. It does not have a semitropical climate, nor does it feature beaches or water sports, but up until the 1970s, “Kalgan” was how Zhangjiakou — located in northern China’s Hebei province, near Beijing — was widely known in the English-speaking world.

Since jointly hosting the 2022 Winter Olympics with Beijing, Zhangjiakou has become best known as a top winter sports destination, but it has a long and storied history as a destination for far-flung visitors in its own right. For centuries, the city occupied a strategic position between Hebei and Inner Mongolia, functioning as a vital hub of transportation and trade between the Han and Mongolian peoples. Even the name “Kalgan” originates from Mongolian, meaning “gate in a barrier” or “frontier.”

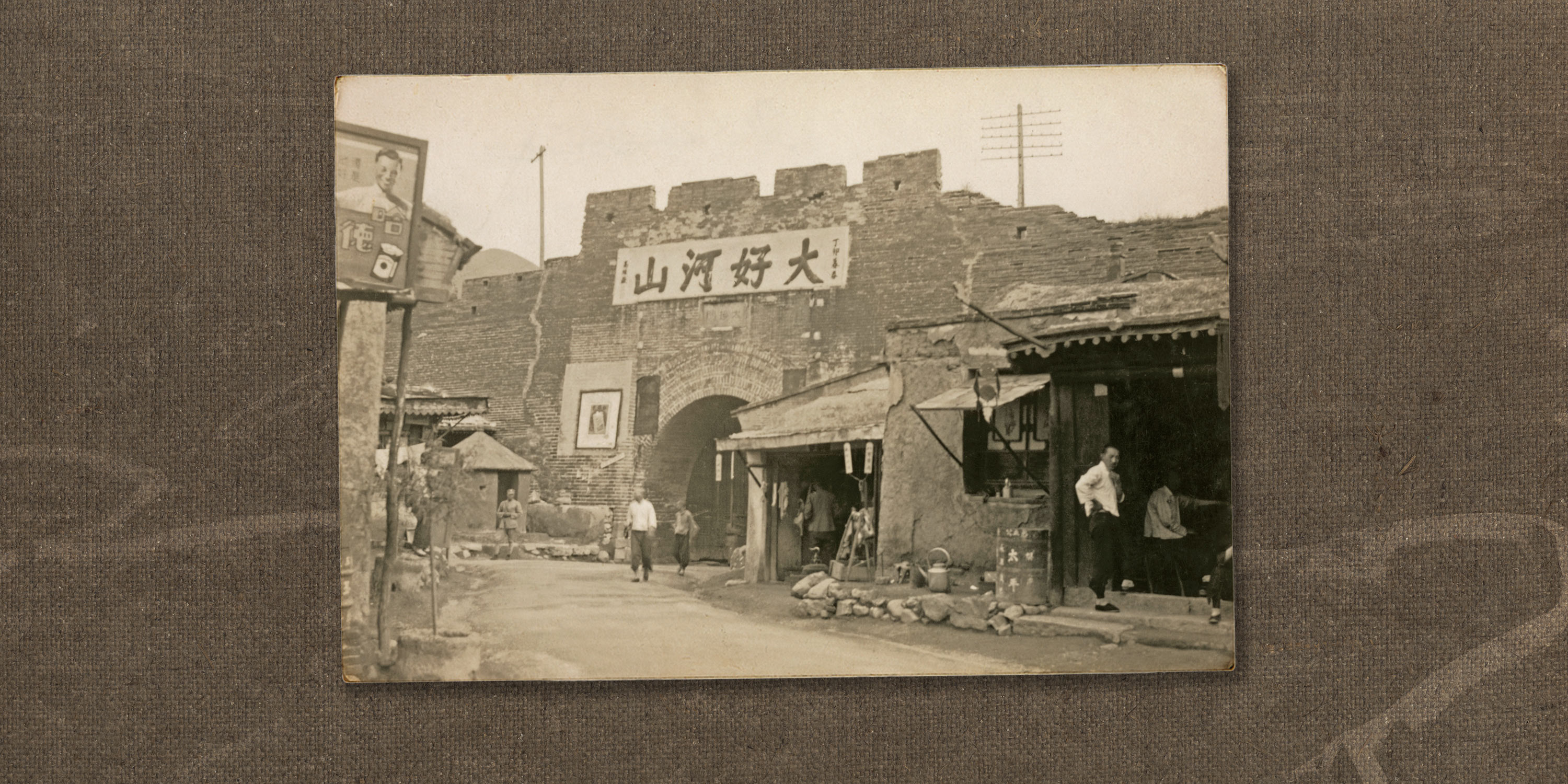

In a broader sense, the name may have signified the city’s original status as a “gate” for travel, trade, diplomacy, and cultural exchange. Yet “gate” also immediately calls to mind the city’s most iconic landmark, Dajingmen, or the Great Border Gate. Established in the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Dajingmen was one of the four major passes of the Great Wall, guarding the northern gateway to the capital Beijing. Now inscribed with the powerful characters da hao he shan — “grand rivers and mountains” — by a general of People’s Republic of China, it has stood as a military bastion, a trade checkpoint, a land port for commerce, and the beating heart of Han-Mongolian exchange. It just may be that the city was named after the gate as commerce flourished and the population grew.

After the 19th-century Western powers forced China to open its market, Kalgan became part of the global trade system and featured in Western travelogues, reportage, and memoirs. Through these writings, the city of Kalgan entered countless households across Europe, the United States, and Australia as a city of consequence, intrigue, and deep historical texture.

One such witness was George Ernest Morrison, the Australian journalist and long-time chief correspondent in China for The Times of London. In a 1913 entry included in “The Correspondence of G. E. Morrison,” he records how a Mongolian noble eager to return to China asked that “arrangements should be made for his safe conduct through the Chinese lines to Kalgan” as he made his way back from today’s Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia’s capital, which was under the Russian Empire’s influence. This detail and the logistics behind it offer a glimpse into early Republican-era geopolitics, yet also testify to Kalgan’s strategic importance as a destination and a gateway to central China.

The American scholar Elizabeth Kendall also described Kalgan in her 1913 travel memoir “A Wayfarer in China: Impressions of a Trip Across West China and Mongolia.” Writing of the Peking-Kalgan Railway, or the Beijing-Zhangjiakou Railway — China’s first domestically built railway, completed in 1909 — she praised its chief engineer Jeme Tien-Yow, also known as Zhan Tianyou, for his outstanding achievement, calling the train “an honest piece of work.” The railway not only linked Peking with Kalgan but also symbolized China’s early mastery of modern industrial engineering and served as a gateway to modernity.

Among Kalgan’s most unexpected visitors was a future U.S. president — Herbert Hoover. In his autobiography “The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover, Years of Adventure 1874-1920” — which was published just one year before Asimov’s “Foundation and Empire” — Hoover recalled an 1899 trip to the city when he was a young mining engineer surveying China’s coal resources.

“I came into Kalgan, a gate to the Great Wall of China, on Christmas Eve, with snow and temperatures below zero.” The next day, he visited a local American Mission which he described as being “alive with Christmas preparations and joyousness.”

Beyond its role in transportation and diplomacy, Kalgan also gained global recognition because of the fur trade, which became a pillar of the city’s international reputation. It had been a major center for fur distribution since the Ming dynasty, even earning the nickname “the Capital of Pelts.” Yet over time, the word “Kalgan” became synonymous with a prized commodity: Kalgan lambskin a product that would eventually overshadow the city’s name.

The linguistic transformation from place to product entered English through commerce. In 1930, American fur merchant Max Bachrach published the industry-defining guide, “Fur: A Practical Treatise.” He described Kalgan as a crucial junction on the trade route linking Kyakhta, located just north of the Mongolia-Russian border, and Peking, from which its lambskin was distributed across northern China and beyond. Through this commercial usage, Kalgan gradually became, in English, a generic term for a type of luxury lambskin.

In 1960, The Guardian introduced Kalgan lamb to British readers with excitement, calling it a fur “never seen in London before.” By 1970, The Guardian had adopted a more understated and familiar tone — “A wild suede coat may be trimmed with shaggy Kalgan” — demonstrating how Kalgan had become part of everyday fashion discourse, a mark of a word’s integration into the English lexicon.

In 1972, The Times took the final symbolic step by printing the word in lowercase — kalgan — beneath a fashion photograph of jackets lined with white lamb fur: “Tank top and battle jacket lined in white kalgan lamb.” No longer a proper noun marking a distant frontier city in China, the word had become an ordinary name for a type of material. Linguistically, Kalgan had completed its journey from place to product, from China to the world.

As for the city itself, the name changed when the pinyin romanization system was adopted in the 1950s, transforming Kalgan into Zhangjiakou — literally, “Zhang’s Gateway”— in honor of a local Ming-dynasty official. Yet traces of Kalgan remain. The Encyclopedia Britannica continues to list the city primarily under its old name, citing Kalgan as “the name by which the city is most commonly known.” A search for “Zhangjiakou” even redirects the reader to “Kalgan,” a subtle reminder of the city’s once firm place in Western geographical knowledge and a window to an older worldview.

Many now know the city as Zhangjiakou, gleaming anew under Olympic snow, a far cry from Asimov’s subtropical planet that bears its former name. Yet beneath the modern ice and steel lies the dusted gold of another era — when the city was called Kalgan, when traders, engineers, journalists, and presidents passed through its gates.

(Header image: Dajingmen, or the Great Border Gate, inscribed with the characters “grand rivers and mountains,” in Kalgan (now Zhangjiakou), 1934. J.N. Behrens/Royal Geographical Society via VCG)