The Mainstreaming of Social Science in China Isn’t Necessarily a Good Thing

Browse Chinese social media and you will notice an intriguing development: posts and comments by young Chinese internet users are becoming increasingly academic.

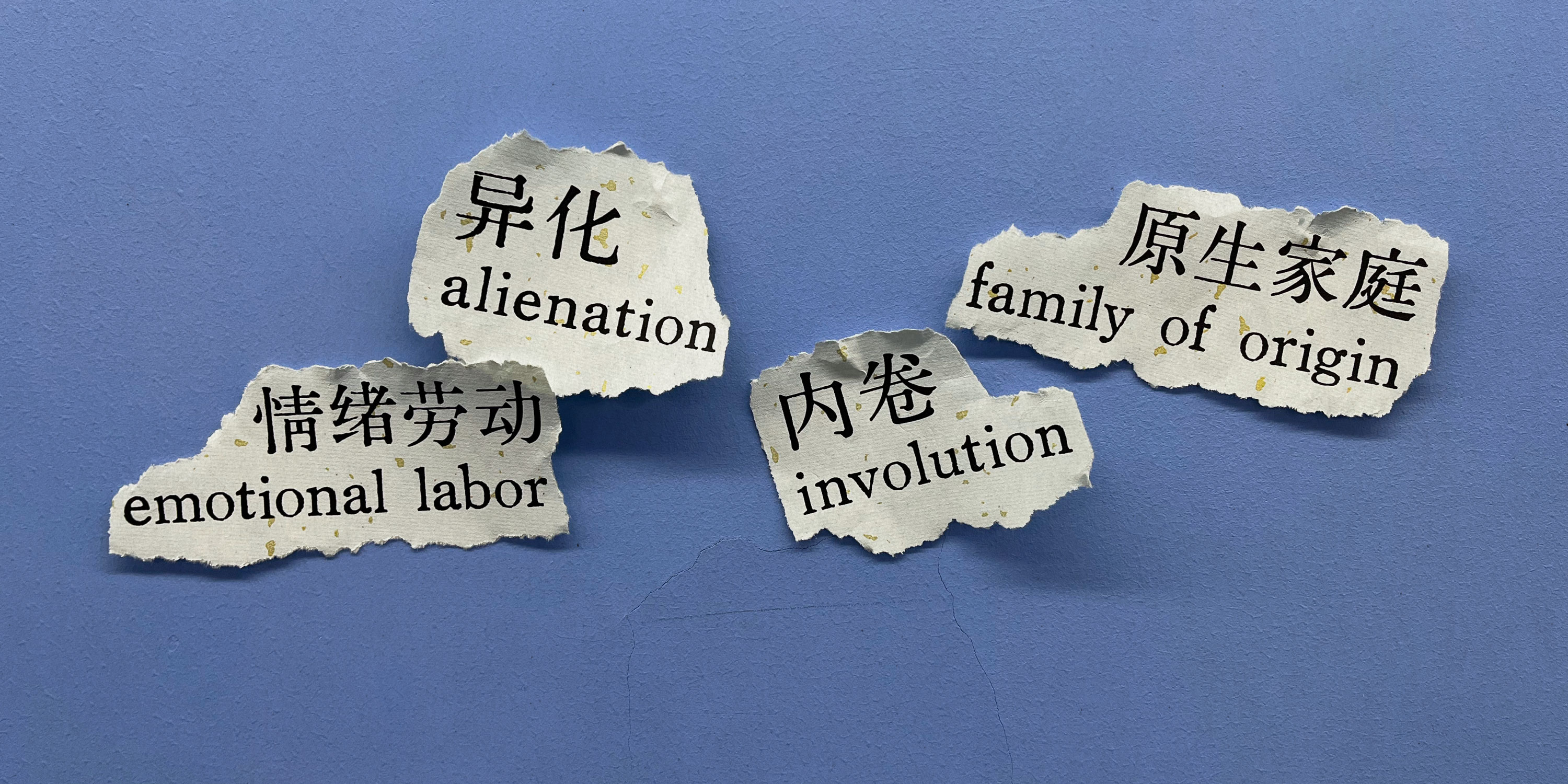

We often see abstruse terms in Chinese online spaces, including “involution,” “alienation,” “emotional labor,” and “family of origin.” These concepts originated in the social sciences, such as sociology, anthropology, and psychology.

“Involution,” for example, was first introduced by anthropologist Clifford Geertz in his study of the agricultural economy of Java Island, describing a situation in which labor input was continuously increased on limited land that was intensively cultivated, and yet the output per unit failed to improve significantly. Now, it is often used to describe how intense efforts to compete don’t yield any benefit.

Similarly, “family of origin” is a specialized term commonly used in psychological counseling and psychotherapy when examining how early experiences shape thinking patterns and attachment styles. However, this term is no longer confined to textbooks or therapy sessions and can now frequently be spotted in posts and comment sections across Chinese social media to explain certain personality traits.

At first glance, it would seem as if the introduction of academic concepts from the social sciences would enrich public debate by adding more specialized knowledge, thereby giving it greater depth. Paradoxically, however, these academic terms have failed to generate discussions that are any more substantive and have instead rapidly evolved into simple labels that can be shared online, sometimes even serving as abrupt conversation enders.

Until about a decade ago, the public largely relied on the investigative reporting and in-depth coverage of traditional media — such as newspapers, magazines, and television — to understand Chinese society. Public intellectuals participated in public debates and acted as a bridge between specialist knowledge and ordinary people. This public-mindedness was not merely about the transmission of information, but a process of integrating the wide range of individual experiences into a shared reality through ongoing public discussion.

As social media has grown, traditional media’s abilities to set the agenda have weakened, while public intellectuals have gradually yielded public space. However, people’s need to make sense of society has not gone away. Specialized concepts and theories from the social sciences have thus entered people’s vocabulary. But as these terms have spread rapidly through digital platforms like never before, they have at the same time become fragmented.

A typical example is “involution.” The word first did the rounds on Chinese social media in 2018 and quickly gained popularity, even being named word of the year in 2021. Today, it is still widely used by many to describe a sense of exhaustion produced by intense competition. By giving social anxiety such a recognizable name, “involution” quickly became a widespread emotional label online.

However, the term also evolved as it was shared. For instance, particularly diligent students are now sometimes jokingly referred to as “involution kings.” Similarly, “family of origin” is often used as a shorthand way to blame one’s parents, all the while completely ignoring the complexity of individual development and the need to understand one’s parents’ own backgrounds.

Theory is no longer a starting point for understanding the world but a way for people to judge themselves. While it offers frameworks for explaining personal circumstances, it does not necessarily foster genuine mutual understanding or provide a solid basis for collective discussion and action. Complex histories and social realities are reduced to objects of blame, with moral judgment replacing attention to lived experience. The result is conclusions that appear precise but remain shallow.

Behind this shift lies a transformation within academia itself. Research in the humanities and social sciences has become increasingly specialized and has gradually moved away from public concerns. Scholars tend to focus on debates within their own disciplines, and their research agendas are often influenced more by publication metrics. Additionally, under the “up-or-out” system, which pressures individuals to seek a promotion within a set timeframe or face dismissal, evaluations affecting career advancement are more closely linked to academic output. This can lead to the marginalization of public-facing writing and less engagement with social issues.

At the same time, changes to the media have exacerbated this problem. While social science concepts have gained unprecedented exposure in digital spaces, online platforms emphasize speed, emotion, and interaction over depth and sustained interpretation. Different social media platforms are also separating audiences and thus making lasting public discussion even more unlikely.

For example, on China’s TikTok-like platforms Douyin and Kuaishou, social science knowledge is severely compressed. Complex arguments are reduced to seconds-long clips, catchy slogans, or emotional judgments, while relationships that originally came with context are recast as being ones of straightforward cause and effect. Remarks made by experts are often edited into soundbites that can be shared easily and are then repackaged to fit preestablished narratives. This rhythm undoubtedly increases the speed of dissemination, but it also degrades critical thinking by creating simple conclusions that are optimized for transmission.

On Xiaohongshu, better known as RedNote in the West, social science knowledge is utilized in a different way. Here, academic concepts are not used for interpreting and discussing social structures, but rather as resources for explaining personal feelings and managing one’s inner state. Terms like “emotional value” and “East Asian family relationships” are used to make sense of real-life issues such as workplace stress and intimate relationships. This allows scholarly concepts to smoothly enter the public sphere, but also brings a tendency toward “flattening.” In other words, concepts are primarily used to name experiences, before swiftly transitioning to consumer-oriented solutions — such as relevant books, courses, therapies, or products. Theories designed to encourage reflection and discussion gradually become mechanisms for self-management and for guiding people’s consumption.

On more “old-school” digital platforms, such as posts on microblogging site Weibo or messaging app WeChat, social science appears to contract inward. Content is largely presented in the form of academic paper abstracts, journal article suggestions, and academic account recommendations, mainly serving to disseminate information within academic circles. This is of course invaluable for researchers and has even become one of the main ways for academics to stay up to date on relevant matters, but it rarely serves as a genuine space for public discussion.

Different platforms’ algorithms and content styles funnel audiences into separate spaces, fragmenting public discussion and preventing sustained engagement with shared issues, thereby reshaping and diluting social knowledge.

As economic growth slows, the room to change personal circumstances shrinks. Without effective public deliberation, it becomes difficult for the public to engage in meaningful discussion of a problem, let alone envision solutions, and thus people reach for labels to put on their situations. Theory shifts from a tool for understanding into a container for feeling, sometimes a placebo. Anxiety is voiced yet rarely becomes action, attention turns inward, and the possibility of change is compressed.

In order to rebuild public discussion, we need new media forms capable of supporting depth, time, and experience. Encouragingly, some alternative forms have already started to emerge. Long-form podcasts — both audio and video — are gradually accumulating stable and committed audiences, which suggests that attention patterns are not immutable. Some people have grown weary of the short-form, fast-paced content that currently dominates and are willing to slow down, listen to complete conversations, and accommodate reflection and hesitation. This shift encourages a return from abstract concepts to concrete experience and allows structural analysis to return to everyday life.

In the end, we also need to rethink what “public knowledge” really means. Its value is not in giving people ready-made answers, but in helping them connect their personal situations to larger social structures. Rebuilding spaces for public discussion is not about removing disagreement, but about restoring mutual understanding, widening how we imagine the future, and encouraging people to act.

Translator: David Ball.

(Header image: Ding Yining/Sixth Tone)