Work It Out: Why More Chinese Students Pick Skills Over Degrees

In 2024, Ke Chenxi scored high enough on the gaokao, China’s gruelling college entrance exam, to qualify for private universities. He enrolled in a vocational college instead, passing on an option many families still see as a route to professional stability.

With a mortgage at home and an older sibling already in university, Ke and his family questioned the return on another four-year degree. At Wuhan City Vocational College, in the central Hubei province, the early childhood education program promised shorter courses, intensive internships, and faster entry into work.

“What attracted me was the hands-on training and the chance to intern early,” Ke tells Sixth Tone. “Compared with university, it’s more practical and gets me ready to work.”

Long stigmatized as a fallback for weaker students, vocational education is now attracting more students who qualify for university. With a record 12.22 million university graduates entering the job market in 2025, competition has sharpened and employers are placing greater weight on practical skills.

That shift illustrates what Gao Shanchuan, an associate professor at Shanghai’s Fudan University, describes as the weakening of the “earning effect” — the long-held assumption that academic credentials reliably deliver higher pay.

“What’s changing,” Gao says, “is that young people are starting to evaluate education more pragmatically. If vocational training leads to stable jobs and a reasonable income, its social standing will rise over time.”

Official data show that employer demand for master’s graduates fell from 20.3% in 2024 to 17.4% in 2025, while demand for vocational graduates rose from 8.5% to 11%, signaling a growing preference for technical skills. In practice, vocational graduates posted the highest job offer rate in 2024, outperforming every other group.

Policy is now moving in the same direction. China’s Outline for Building a Strong Education Nation (2024–2035) elevates vocational education to a national priority, committing to expanded funding, upgraded facilities, and the rapid development of a modern skills-based system.

Experts expect rapid expansion, with vocational undergraduate institutions set to grow in the coming years alongside renewed interest in so-called “skill-based universities.”

On the job

Signs of that growth are already visible in Wuhan.

The provincial capital is one of China’s largest higher-education hubs, home to more than 80 universities, and has long represented opportunity — and fierce academic competition — particularly in engineering and high-tech fields.

Yet it is also where vocational education has gained some of its strongest footing. Graduates are finding work as quickly as — and sometimes faster than — their university peers, with placement rates at some colleges exceeding 98%.

For Ke, that gap helps explain why more students are weighing outcomes over the label on a degree. “Don’t choose a university just because your score allows it,” he says. “Vocational education delivers practical skills that prepare you to work right after graduation.”

He points to two reasons. Speed comes first: his three-year early childhood education program concentrates on kindergarten-ready skills, from activity design to emergency response and parent communication. Then experience. Extended internships place students in classrooms long before graduation.

“That’s what gives us an edge,” Ke says. “By the time we graduate, we’ve already spent long periods working on the frontline.”

Zhuo Ping, a professor at Ke’s college, says vocational education is increasingly being redesigned around labor-market demand rather than academic hierarchy.

In her program, kindergarten principals teach in classrooms, faculty spend time each year working in kindergartens, and courses are continuously updated to reflect changes in practice. The college has also invested in simulation labs that replicate real workplace settings.

Zhuo does not expect vocational education to replace universities. Degrees still carry weight, she says, and tradition remains strong. But she sees a shift underway, as earlier career guidance encourages students to choose paths based on aptitude rather than prestige.

“This reflects a broader shift in how society assesses talent,” she concludes. “We are moving from a narrow focus on credentials toward a more substantive recognition of ability.”

That’s why Wuhan’s vocational colleges work closely with local companies, particularly in manufacturing and technology, shaping training around industry input rather than fixed academic tracks.

Xiao Mian, an HR recruitment supervisor at Wuhan Yunge Cultural Media Co., Ltd., sees the results firsthand. She says vocational graduates tend to execute well, adapting quickly and handling hands-on tasks such as filming and editing with discipline.

Their weakness, she says, lies beyond their assigned role. Many focus narrowly on individual tasks and lack experience with cross-role collaboration or project-level thinking. Xiao prioritizes candidates who “see what needs to be done,” not just what they are told.

Her company recruits vocational graduates mainly for host and content quality inspector roles, and works with colleges through a “project-order class” model that places students on real projects in their final semester.

Even so, Xiao says classroom teaching often trails industry change. Sending teachers into companies to work on live projects, she argues, would better equip them to teach collaborative, project-based skills.

New math

For students, the decision increasingly comes down to speed, specialization, and where those choices lead after graduation.

Like Ke, Cai Minghong met the undergraduate admission threshold, but chose the same program. His parents supported the decision from the outset, confident in the field’s employment prospects and seeing little advantage in an ordinary bachelor’s degree unless it came from a top-tier institution.

Graduating in June, he plans to look for work in and around Wuhan, considering further education only if he fails to secure a suitable position. “I know I’ll be competing with graduates from prestigious universities,” Cai says, “but in teaching practice and classroom management, I think I have an advantage in a job market that increasingly rewards technical competence.”

Ke, too, plans to work in and around Wuhan, estimating starting salaries of around 3,500 yuan ($504) at public kindergartens and about 4,000 yuan ($578) in private ones — slightly lower than what many local university graduates earn at entry level. Within one to two years, he hopes to lead his own class; within five to eight years, to move into management.

Surrounded by universities and degree-driven peers, Ke says he feels pride rather than pressure when he talks about his college. In local hiring circles, the early childhood education program is well regarded, with alumni frequently recognized in interviews — proof, in his view, that the vocational path can carry weight.

About 250 kilometers away, Xiangyang City’s vocational education system is built tightly around specialized local industries, particularly automotive manufacturing.

Li Hua, who spoke to Sixth Tone on condition of anonymity, said he entered the mechatronics program at Xiangyang Polytechnic after narrowly meeting the admission line. His parents did not push for any specific plan, but his secondary vocational school teachers encouraged further education as the safest option.

At vocational college, training quickly shifted toward hands-on work. Competition-based training pushes students to apply classroom knowledge in real-world settings. “Through competitions, we reinforce our skills and see clearly where we need to improve,” Li says.

He estimates that motivated mechatronics graduates can typically earn more than 6,000 yuan a month. For himself, he says a starting salary of around 8,000 yuan is reasonable — slightly above Hubei’s average monthly income of about 7,500 yuan in 2024 — and sees professional certifications as the most direct route to higher pay.

But Li acknowledges the limits of vocational programs. During an internship at a state-owned enterprise, undergraduate interns — including those from private, second-tier universities — were placed on “reserve cadre” tracks and identified early for management roles.

“A degree still makes a difference,” he admits, “but long-term success hinges on the ability to solidify skills and gain experience at the grassroots level.”

Wang Jiahao, 23, experienced vocational education at its most effective. After graduating in architecture from Xiangyang Polytechnic, he described training that was skill-focused and repetitive, with instructors closely involved in ensuring students mastered practical tasks.

“Teachers patiently support those eager to learn, even when starting from weaker foundations,” he says. Through competitions, scholarships, and steady progress, Wang felt his abilities take shape. “I could clearly see my growth,” he adds. “I felt like I had truly learned something.”

Advancing to a civil engineering program at a local university proved more disorienting. Wang chose the major to meet admission requirements rather than interest, a compromise that weakened his motivation.

Undergraduate study, he says, was more theoretical and self-directed, with less hands-on practice and guidance. Unlike vocational training, where teachers worked alongside students, university instructors emphasized independent study. “It’s been hard to adjust,” Wang says. “Sometimes it feels like I’m here just for the degree.”

Additional reporting: Sun Rong; editor: Apurva.

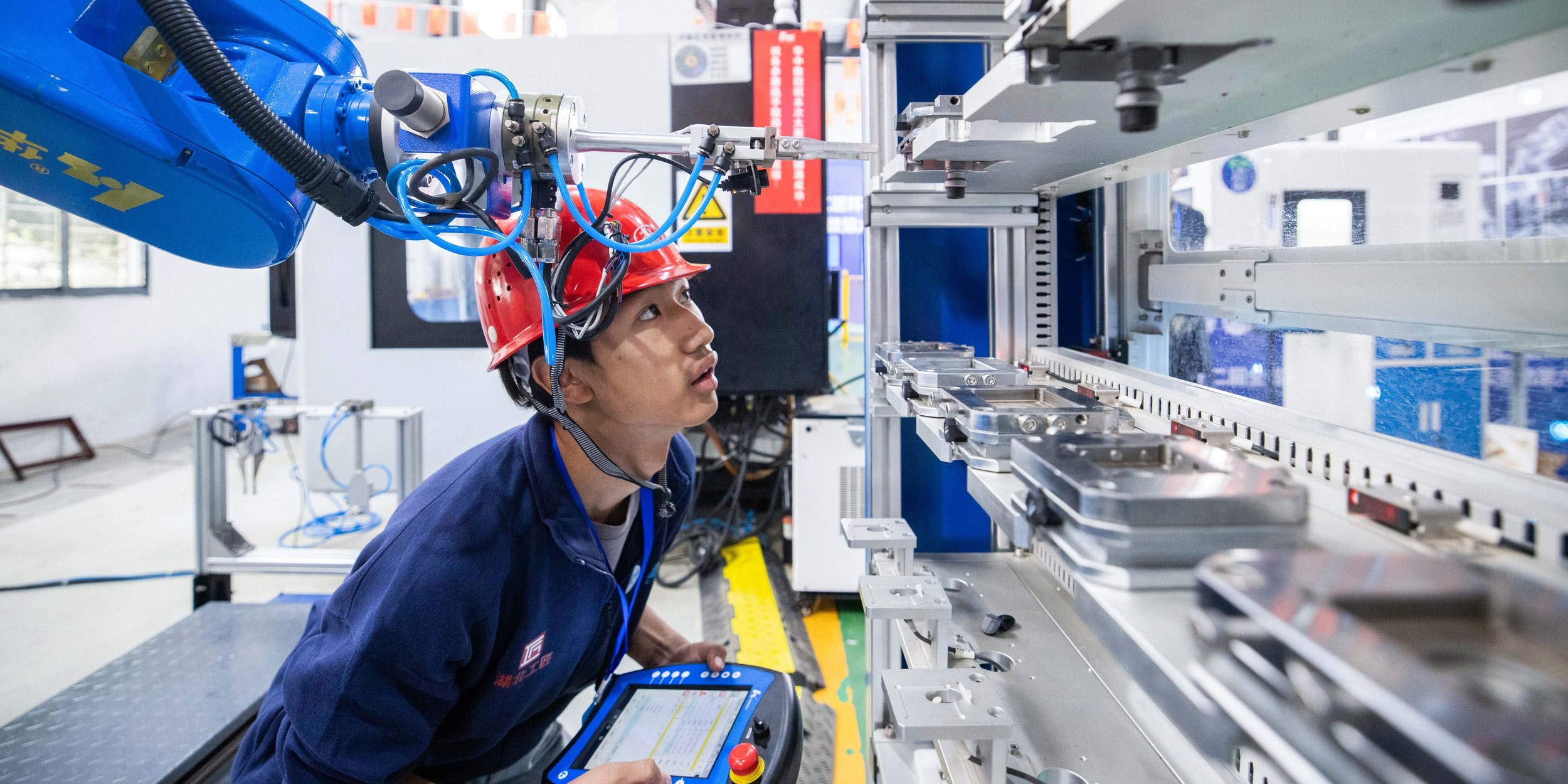

(Header image: A student checks equipment during a vocational skills competition at Ezhou Vocational University, Hubei province, 2023. Xue Ting/Hubei Daily/VCG)