The Shanghai School Opening Hearts and Minds on Autism

“I never imagined my son would be able to ride a bike on the street — so the day he rode out from the school with his classmates, I just wept uncontrollably.”

Ao Yanqiu’s son, Zi’ao, was diagnosed in the early 2000s with severe autism spectrum disorder, or ASD, a congenital neurodevelopmental condition that involves significant social communication challenges, restricted behaviors, and limited abilities in learning and adaptation. He was just months away from his second birthday.

The diagnosis was a devastating blow for Ao and her husband, at the time a young Shanghai couple whose careers were just starting out. Despite their precarious financial situation, they decided that Ao should quit work to care for Zi’ao full time.

With little specialized support for parents in their position, the couple initially struggled on alone. As Zi’ao would scream and fight whenever they tried to take him to the local park, Ao had to devise her own “desensitization therapy” to help him get more comfortable with different environments.

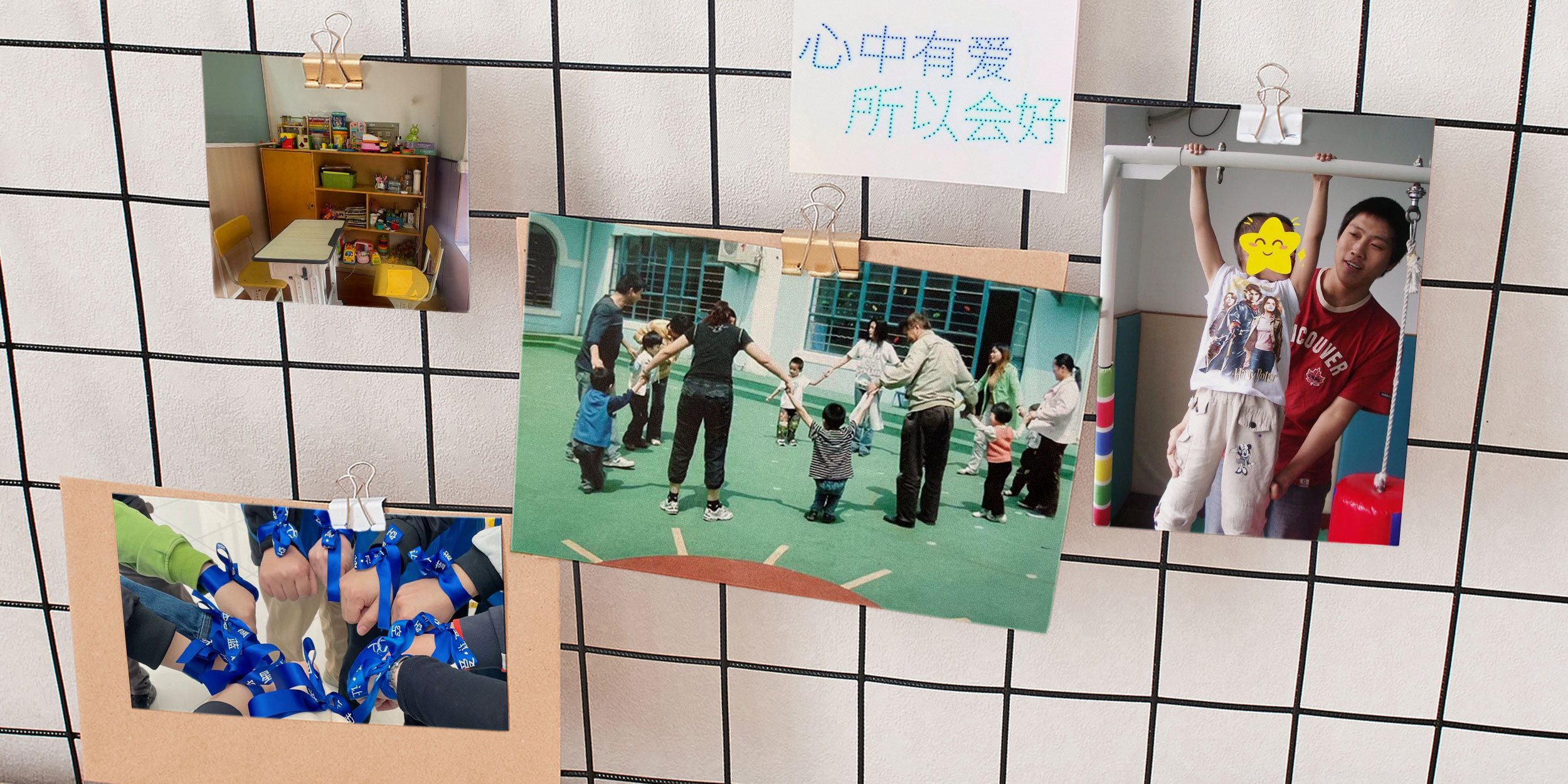

Then, in 2005, hope arrived in the shape of the Shanghai Aihao Children Rehabilitation Center, a newly launched nonprofit social service organization dedicated to educating children with ASD.

The center, which celebrated its 20th anniversary on Dec. 6, has since served more than 5,000 individuals — from preschool children to adults as old as 29 — helping them better integrate into classrooms and wider society, as well as providing essential skills for employment and independent living.

However, two decades on, those involved in raising awareness of ASD and its long-term impact on families in China say that efforts to close the gap in support and work opportunities for autistic people are still just beginning.

Opening doors

Zi’ao was Aihao’s second-ever student. The first was Baobao, whose mother Yang Xiaoyan founded the center. Baobao was around 3 years old when he was diagnosed with moderate-to-severe autism with intellectual disability in late 2003.

Like Ao, Yang had searched desperately for whatever medical advice and educational opportunities she could find. Back then, Shanghai had only a handful of institutions that offered autism treatments.

“My family is relatively well-off, but my child’s development was still daunting. One can only imagine what other autistic children and their families had to go through,” Yang says. After two years, exasperated by the lack of support, she decided to open a special school of her own.

At the start, Aihao had five specially trained teachers to guide rehabilitation and learning. Yang, who believes that “professionalism is the greatest form of kindness,” began raising funds to invite experts from China and abroad for forums and symposiums on autism and educational intervention, and organized 160 free lectures for parents.

Liu Qihe, the center’s executive director, has been with the school since day one. A graduate of Nanjing Normal University of Special Education, he is now responsible not only for teaching the children but also for training its academic staff. He says it takes three to six months to get a new teacher up to speed, explaining that their job isn’t simply “child care,” it’s about driving measurable progress in each student’s development.

“With the professional knowledge I have now, as long as the autistic child doesn’t have a serious intellectual disability, I’m confident that they can be brought increasingly close to the level of their peers through step-by-step cognitive training,” Liu says.

However, this requires immense cooperation from parents. “Just as any student will forget what they have learned if they don’t review, a child with autism will regress if they don’t have consistent training and reinforcement in the home,” Liu adds. “They need their parents’ patience and sustained support — not all autistic kids are lucky enough to get that.”

Autism typically manifests before the age of 3, after which symptoms become more pronounced, with many children requiring long-term rehabilitation and special education. Early detection and intervention are essential, as the younger the child, the greater their brain’s developmental plasticity.

“If we’d missed that critical period for my son’s language development, he might not be who he is today,” says Ao, who started spending six days a week at Aihao with her son, and even moved her family closer to the center.

She recalls that Zi’ao was unable to make eye contact at first, and she would have to hold his hands and guide him in following his teacher’s movements. Slowly, he progressed from physical aping to vocal imitation, then to recognizing objects and people, and finally speaking intentionally and expressing his own needs.

“When I was teaching him to recognize ‘mama,’ for example, he initially couldn’t even form the sound,” Ao says. “He would babble unconsciously. The teacher started by echoing his noises, which puzzled him — why is this person copying me? Eventually, when his teacher made the ‘mama’ sound, he began to imitate it. Once he’d grasped the concept, he began producing the ‘ma’ sound on his own.”

That alone felt like a monumental step for Ao. “When the teacher pointed to my face and said ‘mama,’ my son thought that it was the word for the exact spot being pointed at. Through various methods, the teachers helped him understand the concept of ‘objects’ — only then could he refer to me as mama,” she says, adding that Zi’ao was finally able to recognize his parents around age 7.

Long-term support

One of Aihao’s chief goals is to help extraordinary children integrate into society as equals. As such, in 2012, the center began partnering with mainstream kindergartens — the first collaboration of its kind in Shanghai — with the aim of providing inclusive education for preschool children with autism.

After intensive rehabilitation, many students at Aihao learn to follow instructions and show significant improvements in their behavioral regulation. Those with mild symptoms are then able to enroll in mainstream kindergartens and elementary schools, while more severe cases attend special education institutions.

That same year, Aihao also launched the Blue Ribbon campaign, an initiative that combines online and offline activities for children and parents to promote public understanding of ASD and foster greater acceptance of the autistic community.

Activities have included academic tutoring, choir singing, stress-relief salons, and cycling lessons, which is where Zi’ao learned to ride a bike unassisted from professional instructors. Ao, who joined the choir and now cycles in the city with her son, believes such projects are a lifeline for families.

Public awareness and support for autism have increased over the years, and policy frameworks are gradually catching up. Since 2018, the Shanghai Disabled Persons’ Federation has doubled its annual subsidy for minors with autism to 24,000 yuan ($3,440). The cut-off age for eligibility was also raised from 16 to 18 in 2022.

However, the issue of long-term care and placement for adults with severe ASD remains unclear. Yang points out that existing policies primarily focus on autistic children rather than adults, even though it’s a lifelong condition.

At first, Aihao accepted only children aged 2 to 7, hoping to normalize their behaviors and prepare them for kindergarten and elementary school. In 2018, the center began offering free services to individuals in their teens and 20s.

Jiang, whose grown autistic son has received training at Aihao, says many adults with severe ASD are forced to remain at home all day due to economic constraints, and without proper care they naturally slip into old habits. She appreciates the center for offering her child “somewhere to go,” and adds, “I hope more professional public daycare facilities and interest groups can help families like ours.”

Yang’s vision goes far beyond merely providing a place for them. While the goal for younger children is integration into mainstream schools, the center’s adult program focuses on developing self-care skills. “To put it bluntly,” she says, “if their parents are no longer able to care for them, and they become dependent on others, they must at least be able to maintain their personal hygiene.”

This addresses a question that concerns any parent with a severely disabled child: What will happen to them when I become incapacitated or pass away?

Shanghai’s Civil Affairs Bureau has been piloting elderly-disabled care units at nursing homes, with the aim to provide more than 7,000 beds for individuals with severe disabilities across the city by the end of 2025, according to a government plan.

“The first cases of autism in the Chinese mainland were diagnosed in 1981, meaning those individuals are now at least in their 40s,” Yang says. “The implementation of policies such as elderly-disabled care is increasingly urgent.”

Working solution

Tiantian, who graduated last year with a degree in finance from the Shanghai University of Political Science and Law, is viewed by many parents at Aihao as a benchmark for success. He has high-functioning ASD, which describes individuals with average or above-average intelligence and language skills, but who still face challenges with social communication, sensory processing, and rigid routines.

Since starting elementary school, Tiantian has received systematic training in various life skills from his mother Liu Le and others — such as traveling and shopping independently — in the hope that he will one day be entirely self-sufficient.

In his final year of university, Tiantian completed two internships: one at Inclusion Café, a Shanghai nonprofit that specifically recruits disabled people; the other as part of a social immersion program for autistic individuals, facilitated by a partnership between Aihao and a major chain of convenience stores. These positions exposed Tiantian to professional settings and allowed him to master practical skills like making coffee, taking inventory, and cash register management.

Yet, despite his degree and work experience, his path to full-time employment has remained fraught with difficulties. Liu has worked tirelessly to help her son write a résumé, role-playing workplace scenarios and holding mock interviews, yet he’s been unable to land an office and administrative role.

The family recently had high hopes of Tiantian getting a library assistant position at a school, as he has an excellent memory and a deep love of reading, but he ultimately missed out.

Liu knows that her son has his limitations, “but we’re trying so hard, and he never stops learning. … If he were given an employment opportunity, I or a special education teacher could walk him through the workflow a few times — I just know that he could master it.”

Even internship opportunities for autistic adults are extremely limited, and professional employment guidance is sorely lacking. “For Tiantian, work isn’t just about making a living — it’s an opportunity and a reason to go out and practice social interaction,” Liu says. “Us parents are willing to accompany them to work because we know that if they stay home for long periods and disconnect from society, their social skills will inevitably regress.”

Chen Rongdong, chairman of the Wujing Huiling Community Disability Support Center in Shanghai’s southwestern Minhang District, is among the grassroots leaders calling for solutions to close the employment gap facing adults with ASD.

He envisions creating a talent database for autistic people to better match them with inclusive employers, allowing the right person to excel in the right role. “This is high-quality employment, by which I mean they are hired because they are capable of doing the job — maybe even more so than a non-autistic colleague — not because they are pitied or sheltered due to their autistic identity,” he explains. “With adequate support, autistic adults can contribute meaningfully to society.”

With its Blue Ribbon campaign, Aihao is also continuing to explore pathways for supported employment for individuals with ASD, with much landscape yet to be cultivated.

Yang feels that things are still at the beginning. “I’ve always felt that, while we may never create an isolated sanctuary for them, a different kind of world is possible,” she says. “With every step forward in public understanding and acceptance, with every scientific and medical breakthrough, and — most critically — with supportive policies, a future in which our children can live, grow, and age with grace and dignity is not just a distant dream but is within our grasp.”

Reported by Zou Jiawen.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Paper. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Chen Yue; editors: Wang Juyi and Hao Qibao.

(Header image: Visuals from interviewees and VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)