The 12 Zodiac Signs That Climbed Mountains and Crossed Seas to Reach Ancient China

This is the first of a two-part series on traditional Chinese zodiac.

When archaeologists back in 2017 discovered that semicircle-enclosed crab and ram-horn motifs had appeared on bronze mirrors during the Wu Kingdom period (222–280), they regarded it as proof that Western astronomical zodiac signs had at one point crossed the seas and reached China.

Based on birth month in the tropical year, the 12 astronomical signs bore no relation to the traditional Chinese zodiac animals. All the same, images of these imported star signs would find their way into Chinese culture and traditional works of art.

Pictorial evidence of the signs did not mean that the names and connotations associated with them had been appearing in Chinese districts. The system of astronomy — originating from the ancient Mesopotamian region and maturing in ancient Greece — had reached India through Alexander the Great’s eastern campaigns. Later, as Buddhism began to spread in China in 2 BC, elements of Indian culture entered China, with these cosmic symbols in tow.

In Western Europe, Egypt, West Asia, and Central Asia, the astronomical zodiac served as a coordinate framework for measuring the positions of the sun, moon, five planets, and other celestial bodies, along with astronomical phenomena. However, their imagery and symbols were also important emblems of astral deities and became objects of worship and prayer. For instance, the zodiac representations found in the Dendera Temple in Egypt (circa 25 AD) show remarkable similarities to those on the Kudurru boundary stones of ancient Babylon, which date back to around 1200 BC.

However, by the time images of the 12 astronomical zodiac signs appeared, China had already developed its own distinct tradition of measuring astral phenomena, which used the 28 lunar mansions — segments of the equator that measured the paths of the sun, moon, and five planets traveling across the night sky. Unlike practices in Europe and Central and West Asia, China’s system divided the 28 lunar mansions into four groups for the cardinal directions, each corresponding to a divine animal: the Azure Dragon of the East, the Vermilion Bird of the South, the White Tiger of the West, and the Black Tortoise of the North.

The difference between the systems is significant. In the Chinese constellation system, the 28 lunar mansions vary greatly in width, while the zodiac constellations were equally divided into the 12 signs, each occupying exactly 30 degrees. Even though some of the 28 lunar mansions — such as Fang (Room), Xin (Heart), Wei (Tail) — overlapped with portions of Scorpio, they were ultimately distinct systems of celestial knowledge, belonging to different cultural traditions.

All the same, once images of the zodiac signs entered China, they would interact with Chinese culture for years to come. Once all of the 12 zodiac signs had been transliterated from Sanskrit into Chinese by the Hindu monk Narêndrayaśas of the Northern Qi dynasty by the late 6th century, the influence of the zodiac signs would make its way all across China.

The zodiac signs reached peak popularity during the Tang dynasty (618–907), but this popularity did not diminish the significance of the 28 lunar mansions in astronomy and astrology. It did, however, cause quite a stir when it came to the zodiac’s implications on celestial deity worship and star lore.

The names and images of the 12 zodiac signs began to frequently appear in Buddhist and Daoist texts and iconography. In northwestern China’s Dunhuang Mogao Caves — particularly in Cave 61, on the north and south walls of the corridor — images of the 12 zodiac signs encircle the Tejaprabhā Buddha transformation scene as deities to which ordinary people would make offerings or seek blessings.

Suddenly, this classic Buddhist scene was in conversation with the lion that is Leo, the ram of Aries, and the unmistakable image of a bull with horns for Taurus. The flower-adorned vase might also make you pause for a moment, but yes, it is Aquarius — often referred to as the “precious vase” in Chinese texts, typically depicted as containing flowers instead of water, or as a plainly adorned jar.

Then there is the depiction of two young maidens standing together, facing forward, which is a representation of Virgo. In Chinese texts, this is always translated as shuang nü gong (double maiden palace), a term that continued into the Qing dynasty (1644–1911).

Similarly, the image of a large and a small monk together represents Gemini. In Buddhist iconography, which often features the Tejaprabhā Buddha, Gemini is frequently depicted as a man and woman, reflecting the Chinese term for this sign — fu qi gong (husband and wife palace) or nan nü gong (male-female palace).

Lastly, an image of a person leading a horse is none other than the legendary Sagittarius, where the foreign image of a centaur is transformed in Chinese iconography into a human with a horse. This syncretism of the zodiac signs within Chinese visual culture shows the influence of the Western system of constellations while adapting them to local traditions and symbolism, creating a unique blend of Eastern and Western star lore.

The images of the 12 zodiac signs would often appear among the astral deities — such as those encircling the statue of the Tejaprabhā Buddha — becoming objects of supplication in Buddhism and Daoism for ordinary individuals seeking blessings and a way to avert disasters.

Yet as time went on, the cultural significance of the zodiac signs expanded beyond religious practices, reaching into the everyday lives of ordinary people. The concept of star gods — associated with each individual’s birth year, month, or date — became part of folk beliefs, in which people sought their protection or favor in their daily lives. In this way, the zodiac signs played a role in the cultural fabric of society, both in religion and pop culture, offering guidance, protection, and a connection to the celestial realm.

From their journey across the seas and the towering mountains, the 12 zodiac signs have become a part of Chinese culture. With their blend of spiritual and astrological elements, the 12 zodiac signs remain a powerful symbol of both personal destiny and divine intervention.

Portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

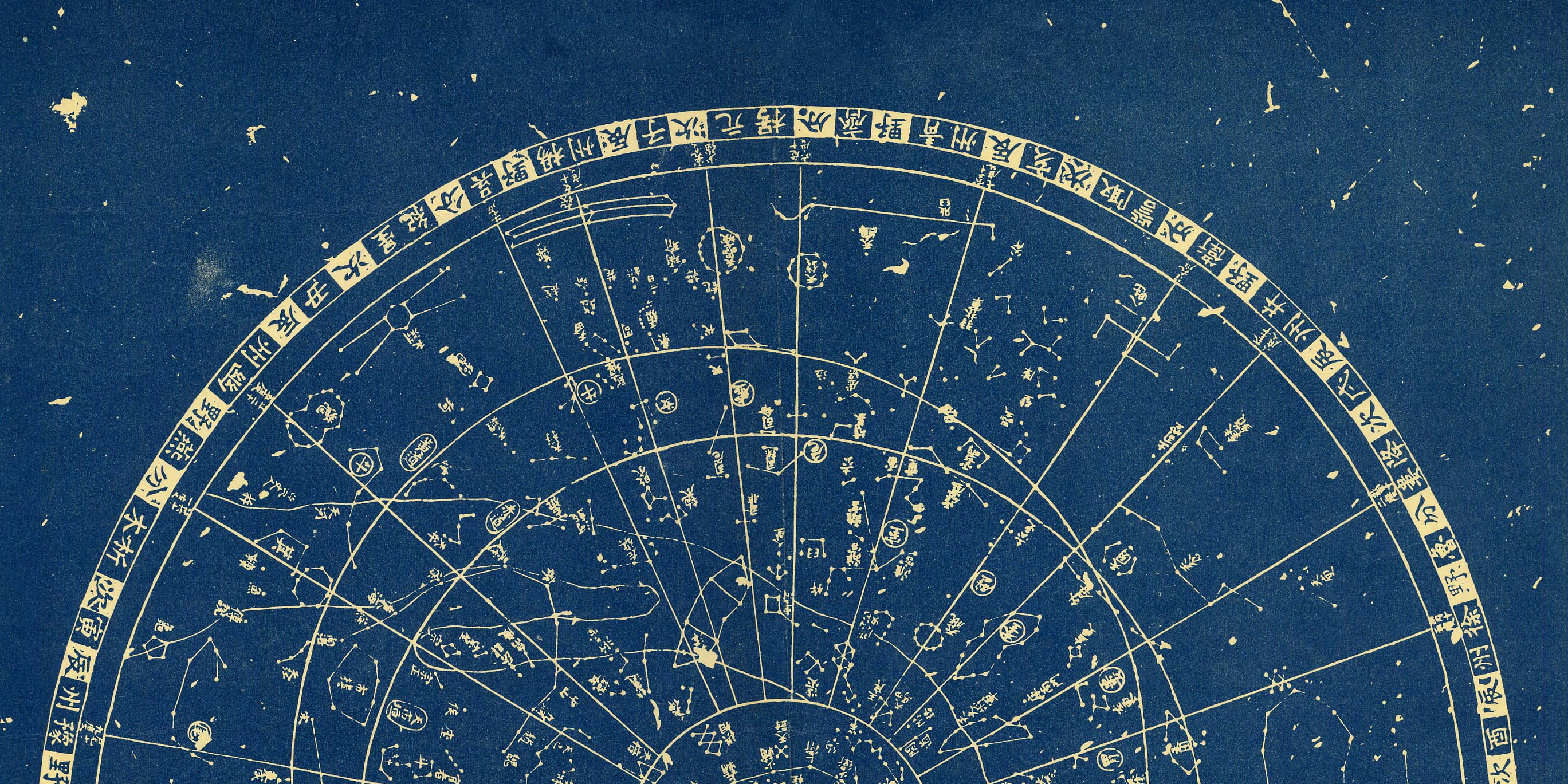

(Header image: Details of a rubbing of “Astronomical Chart,” drawn 1190, engraved 1247, Suzhou, Jiangsu province. From the public domain)