China’s Boar-Hunting Drones Fly Into a Legal Vacuum

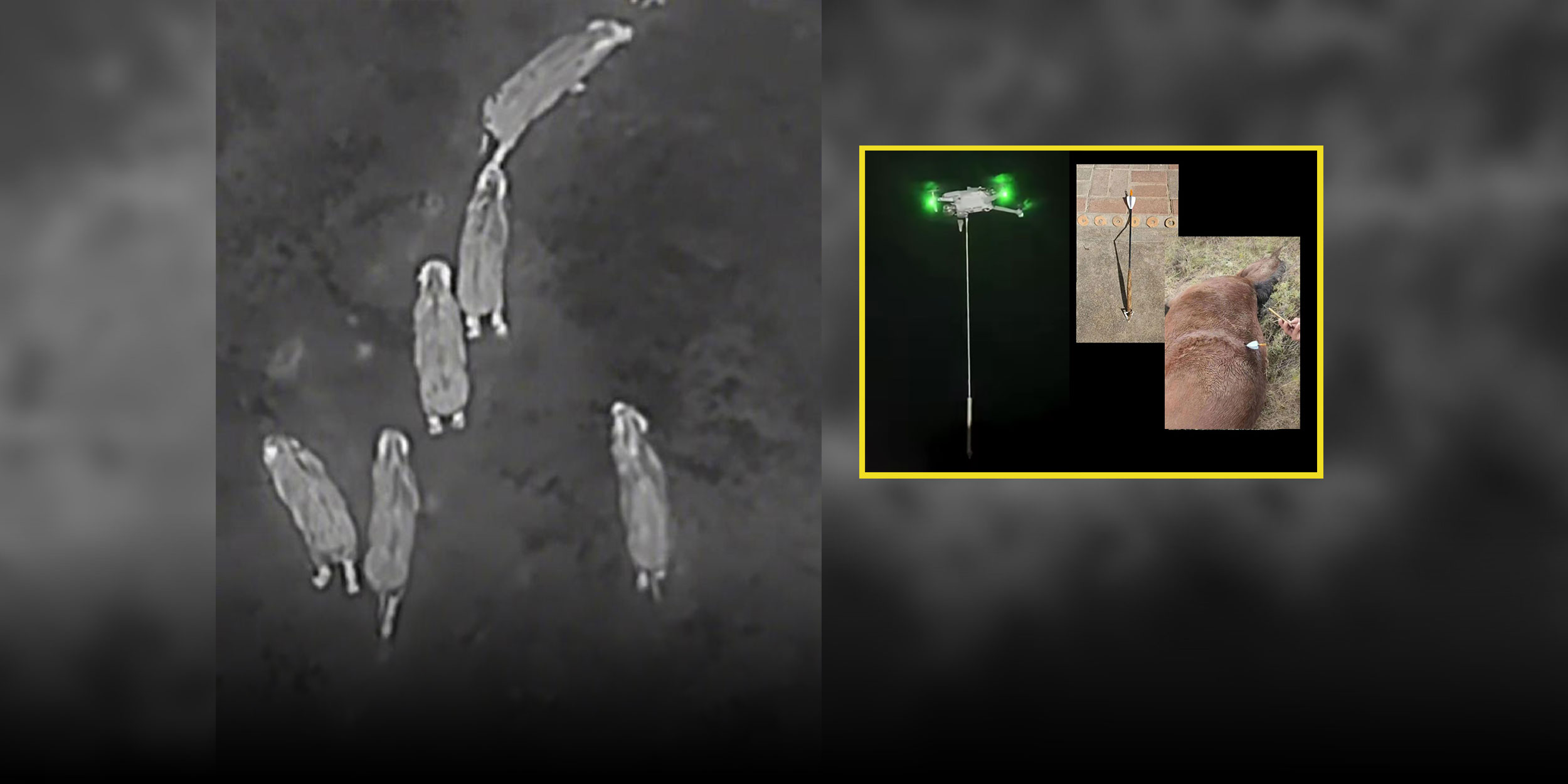

In line with China’s 2023 lifting of its wild boar hunting ban to protect rural crops, drones equipped with thermal imaging and metal projectiles have emerged as an efficient hunting tool.

But widespread misuse, driven by their popularity on social media, has led to questions about their legality.

Since late 2024, cases involving drones used to target protected wildlife as well as livestock have surfaced across China.

In October, one offender was reportedly hunting wild boars but, in heavy nighttime fog, mistakenly killed a horse, later compensating its owner in a legal settlement. Another two offenders who shot and stole a farmer’s free-range goats were detained on theft charges. In many cases, however, legal proceedings stall because the drone operators cannot be identified.

In a case in the central Hunan province this September, metal arrows were found to have been used to hunt muntjac deer, a protected species in China. In a separate case in the same province in November, police discovered three offenders had used net-launching drones to capture 31 protected animals including kestrels, herons, and Chinese hares.

Hunting drones were initially used in China by hunting teams approved and overseen by the government to ease growing human-boar conflicts. In recent years, 26 provincial-level regions across the country have reported injuries caused by wild boars, with some even rampaging through city streets. Local governments have spent millions of yuan compensating farmers for crop losses.

China first banned wild-boar hunting in 2000 after deeming the species to have “beneficial, economic, or scientific value.” But the population soon grew out of control.

In 2023, the central government removed wild boars from the list of protected species. In February 2024, authorities dispatched more than 100 boar-hunting teams across the country to deal with the influx.

In northwestern Shaanxi province, local forestry departments invited drone pilots to kill 200 wild boars between May and October this year, offering bounties of 1,500 yuan ($210) per carcass. Officials have reported drones being far more effective than traditional dog-assisted hunts and causing far less crop damage.

Hunting drones cost approximately 40,000 yuan. Equipped with thermal imaging, many are modified to carry metal arrows measuring roughly 60 centimeters long. Once a target is locked on, the arrows can hit a target from as high as 40 meters in the air at night.

But as drone-hunting videos have gone viral on Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, abuse of the technique has spread rapidly.

Sixth Tone found that buying additional arrow “airdrop” devices for drones costs as little as 100 yuan on major e-commerce platforms such as Taobao, while metal arrowheads and shafts sell for 10 to 100 yuan.

In October, a suspect arrested in eastern Jiangxi province for illegal hunting told police he “got the idea after watching short videos of drones dropping arrows,” then modified a drone with additional parts bought online.

One member of an official hunting team voiced their concern about the dangers of such modified devices to domestic media: “If they’re shooting boars today, they could just as easily hit a person tomorrow.”

Legal experts are now urging regulators to step in.

Under China’s Criminal Law, hunting wild animals — even non-protected species — may constitute illegal hunting if “banned tools or methods” are used. But according to the Wildlife Protection Law, which was enacted in 1988 and last revised in 2022, banned tools commonly refer to traditional weapons such as guns, poison, traps, or electrified nets, not drones or arrowheads.

So far, one jurisdiction — Liuyang City in the central Hunan province — has explicitly listed “using drones or other aircraft to drop javelin- or arrow-like devices” as a banned hunting method.

Han Xiao, a lawyer at Beijing Kangda Law Firm, told domestic media outlet Beijing News that it is difficult to impose a blanket ban on “drone modifications” because such upgrades can also serve legitimate purposes in agriculture and mapping.

The challenge, he said, is defining exactly what constitutes a modification “for illegal activity,” and establishing clear legal boundaries and penalties.

He suggested requiring all drone products to contain built-in, tamper-proof flight data recorders so authorities can retrieve data and secure evidence after illegal incidents.

Editor: Marianne Gunnarsson.

(Header image: Screenshots of drone thermal images as well as a diagram showing how the metal arrows they are equipped with are used to shoot livestock. From Douyin)