The Women Who Translated Chinese Cuisine Into American

Chinese cuisine has captivated the Western palate. Take, for one, the staggering number of Chinese restaurants in the U.S. They outnumber fast-food titans McDonald’s, Burger King, KFC, and Wendy’s — combined.

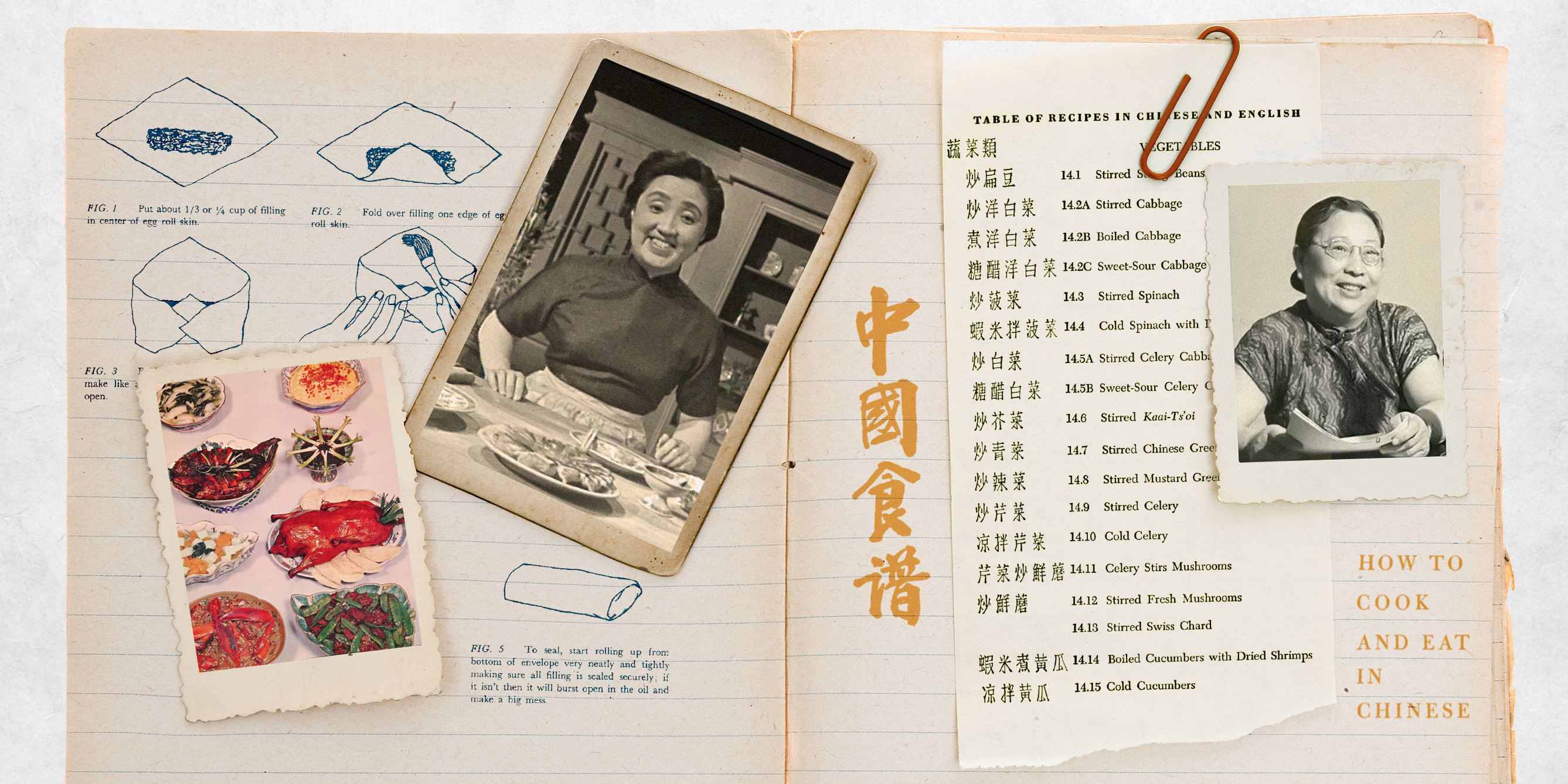

This entry into the annals of global gastronomy could not have been written without the pioneering efforts of two remarkable Chinese women — Yang Buwei and Joyce Chen — who, through books, TV shows, and simply their cooking, turned dishes such as potstickers and moo shu pork into American staples.

Across the mid-to-late 20th century, they didn’t just introduce recipes; they were cultural ambassadors who left an enduring legacy that has profoundly shaped Western language, culture, and dining habits.

With a pinch of irony, one of their stories started with a dislike of foreign food. When 19-year-old Yang Buwei moved to Japan in 1908 to study medicine, she found it difficult to adapt to the local cuisine. It forced her to learn how to cook Chinese dishes. Later in life, after moving to the United States with her husband, linguist Zhao Yuanren, also known as Yuan Ren Chao, her ability to whip up tasty food despite World War II-era shortages gained her much praise from the other university professor wives.

They urged her to collect her recipes in a book. It became a family production, according to the book’s official history. Yang, now using the name Buwei Yang Chao, dictated her recipes to her daughter, Rulan Chao, who translated them into English. Yang’s husband did the proofreading and editing.

The result, 1945’s “How to Cook and Eat in Chinese,” taught the techniques of Chinese cooking with novel precision. For its more than 200 classic recipes, it translated the intuition-based and notoriously vague quantities of Chinese cooking — a “pinch” of this, the “appropriate amount” of that — into the more precise measurements favored by Western chefs.

Most notably, the book communicated the craft and philosophy of Chinese culinary culture with witty linguistic inventions. The family team was the first to translate many terms that are key to Chinese cooking, some of which have since entered common use.

Take stir-frying. The authors coined this compound word to capture the essence of chao, defining it with unique authority: “Ch’ao may be defined as a big-fire-shallow-fat-continual-stirring-quick-frying of cut-up material with wet seasoning. We call it ‘stir-fry’ or ‘stir’ for short.” This distinct definition serves as the earliest recorded evidence for “stir-fry” in the Oxford English Dictionary.

Beyond stir-fry and its derivatives, five other neologisms from the book entered the OED: the seasoning soy jam (a semantic translation for a thicker, sweeter rendition of soy sauce), the technique red-cooking (a direct translation of hongshao), and the food items potsticker (a direct translation of guotie), dim sum, and yuan hsiao (a kind of sweet dumpling).

After the book’s publication in 1945 and some subsequent media attention, it became a sensation. It was endorsed by Hu Shih — China’s ambassador to the U.S. from 1938 to 1942 — who wrote a foreword that predicted the book’s linguistic influence. Anne Mendelson, a noted American food journalist and gastronomy historian, hailed it as “the first truly insightful English-language Chinese cookbook.”

Even more effusively, writer and Nobel laureate Pearl S. Buck, in her foreword, jested that she would nominate Yang for the Nobel Peace Prize, asking: “What better road to universal peace is there than to gather around the table where new and delicious dishes are set forth?”

“How to Cook and Eat in Chinese” became a cultural phenomenon, seeing countless revisions, reprints, and translations, and influencing generations of Western cooks and diners. Following its success, Yang continued to promote Chinese culinary culture through writing. She subsequently authored “How to Order and Eat in Chinese,” which introduced American readers to authentic Chinese restaurant dining, and other books.

Her culinary compatriot Joyce Chen — born Liao Chia-ai — would too become a towering figure in 20th-century American Chinese cuisine. In 1949, at the end of China’s civil war, she moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the U.S. There, she would become known as the “Chinese Julia Child” — a reference to the popular chef and author who brought French cuisine to America.

Chen was an entrepreneur, chef, and educator. She introduced the elites of the Boston metropolitan area to the sophisticated flavors of northern Chinese cuisine, including Peking duck, lion’s head meatballs, hot and sour soup, and moo shu pork. The translation of the latter dish is Chen’s own contribution to the English language, with an inclusion in the OED.

Chen became the first Asian chef to host a nationwide TV cooking program in the United States, wrote the best-selling “Joyce Chen Cook Book,” and pioneered Chinese cooking classes at local adult education centers. Her work elevated Chinese food from exotic takeout to a respectable, aspirational part of American home cooking.

Chen’s entrepreneurial spirit also left an indelible mark: she invented and patented the flat-bottomed wok, which was better suited for American electric stoves, and was a pioneer in commercializing bottled Chinese stir-fry sauces. She famously tried to change the imprecise way Americans referred to jiaozi — as simply “dumplings” — to “Peking ravioli,” a term that, while not widely adopted, was a creative attempt to bridge a cultural gap.

Joyce Chen’s enduring influence on American dining and her trailblazing role as a female entrepreneur and media personality were officially recognized in 2014 when the U.S. Postal Service featured her on a commemorative stamp as one of five “Celebrity Chefs Forever,” a distinction that also included Julia Child. Chen was the first Chinese chef to receive this honor.

Yang Buwei and Joyce Chen, each in her own distinct way, performed a vital act of cultural translation. They successfully interpreted the complex, nuanced world of Chinese cuisine for a Western audience, going beyond simple recipes to convey the philosophy, context, and joy of the Chinese dinner table.

As culinary ambassadors, media icons, and linguistic pioneers, their collective contributions laid the foundation for the enduring, widespread, and deepening appreciation of Chinese food in the West, forever enriching the global culinary landscape.

(Header image: Visuals from archive.org, VCG, and the public domain, reedited by Sixth Tone)