The Scholar Bringing Marco Polo Back to China

This year marks the 700th anniversary of the death of Marco Polo (1254–1324), the legendary Venetian traveler who introduced Asia to the West.

Yet despite Marco Polo’s widespread recognition in China, there exists only one rigorous Chinese translation of “The Travels of Marco Polo.” Completed by Feng Chengjun and published by the Shanghai Commercial Press in 1936, this translation falls short of meeting modern standards of accuracy, fluency, and elegance. Feng summarized each chapter using classical Chinese, adhering to the literary conventions of that era. Furthermore, he relied on a modern French edition annotated by A. J. H. Charignon that was itself not always accurate.

In 2011, Rong Xinjiang, a history professor at Peking University and a leading scholar of Sino-foreign relations during the medieval period, brought together a study group to annotate “The Travels of Marco Polo.” The group was a who’s who of Chinese medievalists, including experts on Mongol history, Iranian studies, and Chinese relations with the Silk Road kingdoms. While their translation — based on a 1938 edition of the text annotated by A.C. Moule and Paul Pelliot — remains unfinished, their work has already resulted in multiple books on Marco Polo, the Silk Road, and medieval trading hubs like the eastern city of Yangzhou.

In late March, Rong sat down with Sixth Tone for a wide-ranging conversation about his work, the life of Marco Polo, and the uncertainties surrounding his story.

Sixth Tone: You are an expert in Marco Polo studies. But it’s well-known that many people doubt the authenticity of his life and journey. What is your perspective on this?

Rong Xinjiang: Marco Polo definitely existed. His family’s house still stands today. Many contracts from his family have been preserved in the archives of Venice. During that time, Venice’s commercial network extended into the eastern Mediterranean. The Polo family was involved in business, establishing numerous commercial outposts from West to East. Marco Polo’s legendary travels, at least until he entered Yuan dynasty China (1279–1368), can be traced point by point.

In academia, there is no doubt about the existence of Marco Polo. However, there has been controversy regarding whether he actually visited China. For instance, Frances Wood, a British scholar, published the book “Did Marco Polo Go to China?” in 1995. She suggests that Marco Polo might have compiled his travelogue based on Persian-language trade manuals and local rumors. Wood’s viewpoint is not new; the German scholar Herbert Franke proposed a similar idea in 1973.

Additionally, some Chinese scholars have pointed out that if Marco Polo held an official position during the Yuan dynasty as he claimed, there should be relevant records in Chinese official documents. However, conclusive evidence has not been found thus far.

Sixth Tone: Do you find these skeptical viewpoints convincing?

Rong: The mainstream view in academia is that Marco Polo did indeed visit China. As early as 1941, Yang Zhijiu discovered a memorial in the “Yongle Dadian,” a Ming dynasty encyclopedia, that lists the names of three envoys sent to the “Ilkhanate,” in modern-day Iran, which perfectly matches the relevant accounts in Marco Polo’s travelogue.

Furthermore, German sinologist Hans Ulrich Vogel published a book titled “Marco Polo Was in China” in 2012. In this work, Vogel highlights Marco Polo’s detailed descriptions of ancient Chinese salt production processes and his comprehensive records of Yuan dynasty currency — details rarely found in other medieval literature.

Sixth Tone: But as you mentioned earlier, there are no official Chinese records about Marco Polo. Why is that?

Rong: Keep in mind that “The Travels of Marco Polo” contains many exaggerated and even fantastical elements. Moreover, Marco Polo did not write the book himself; it was narrated to his fellow inmate, an author, while he was imprisoned in Genoa.

However, the basic framework of the story remains valid: Marco Polo traveled from Venice to Iran, then through Central Asia, the Tarim Basin, the Hexi Corridor, and finally reached Dadu — present-day Beijing. He met Kublai Khan and later explored many regions in southeastern China before departing from the port city of Quanzhou with the three envoys. He escorted the princess Kököchin to Persia for her marriage, and eventually returned to his homeland.

As for the lack of official Chinese records about him, I personally agree with the historian Cai Meibiao’s view. Marco Polo did not hold a formal official position; instead, he was an “ortoq.” Ortoqs were a special merchant group during the Mongol Yuan dynasty. Mongol khans, princes, and princesses granted various privileges to ortoqs, allowing them to conduct business or engage in usury using royal money and tokens. Most of the profits were handed over to the court and the khan, but a small portion could be kept for themselves. There is even a monument in Quanzhou dedicated to a Uyghur ortoq from this period.

Sixth Tone: So, because Marco Polo was an “ortoq” rather than a formal court official, he is not recorded in official historical documents.

Rong: Exactly. Furthermore, this title not only explains why Marco Polo is absent from official records but also provides clues about his life. If he indeed served as an ortoq under Kublai Khan, he could have lived in China for an extended period even without knowing Chinese.

In fact, Marco Polo probably did not speak Chinese fluently; his proficiency in Mongolian and Persian would have sufficed. This also explains why the Chinese city names and references in “The Travels of Marco Polo” do not always match standard Chinese pronunciation but align better with Mongolian and Persian pronunciations.

Sixth Tone: Can you provide an example?

Rong: Certainly. There is a place mentioned in “The Travels of Marco Polo” called Cotan, located in the southwestern region of today’s Tarim Basin. In traditional Chinese historical texts, this place is often referred to as “Yutian,” while in the official “History of Yuan,” it is called “Odon.” Meanwhile, in Muslim historical sources, the name for this place is “Hotan.” Marco Polo’s “Cotan” clearly aligns more closely with “Hotan” and is quite distinct from “Yutian.”

Sixth Tone: In your opinion, what is the primary value of Marco Polo’s travelogue?

Rong: The unique value comes from the fact that he was a merchant. In Chinese history, those who extensively traveled and left behind travelogues typically fall into two categories: religious figures, such as the Tang dynasty (618–907) monks Yijing and Xuanzang, and diplomats like Zheng He (1371–1433). Merchants’ notes are relatively scarce, but “The Travels of Marco Polo” fills this gap.

If you read this book closely, you’ll notice that Marco Polo observed each place meticulously, paying special attention to local products and commodities. He often commented on which items would be profitable if sold in specific locations. It is precisely this merchant’s perspective that provides us with valuable records about ancient Chinese socio-economic life, distinct from official government documents.

Sixth Tone: Could you provide an update on the progress of the Chinese translation of “The Travels of Marco Polo”? You’ve been working on it since 2011; when do you think we’ll see it in print?

Rong: Our work goes beyond mere translation; it involves extensive annotation. When the book is eventually published, there may be only two volumes of translated text, but the annotations could span six or seven volumes. For instance, let’s take the example of Cotan. We need to provide detailed annotations about the different variations of this place name in various regional literature, the historical changes that the region underwent, and why Marco Polo didn’t mention jade when describing Cotan. Another example: Marco Polo mentioned that the Mongols had a type of garment called “nascisi” (“nasij” in Persian), which was made with gold thread and worn by nobles, making them shine like gold. However, there were several variations of “nascisi.” Which one did Marco Polo actually see? All of this requires us to cross-reference historical and archaeological sources.

You can imagine that this is a painstaking and challenging task. Nevertheless, I believe it must be done.

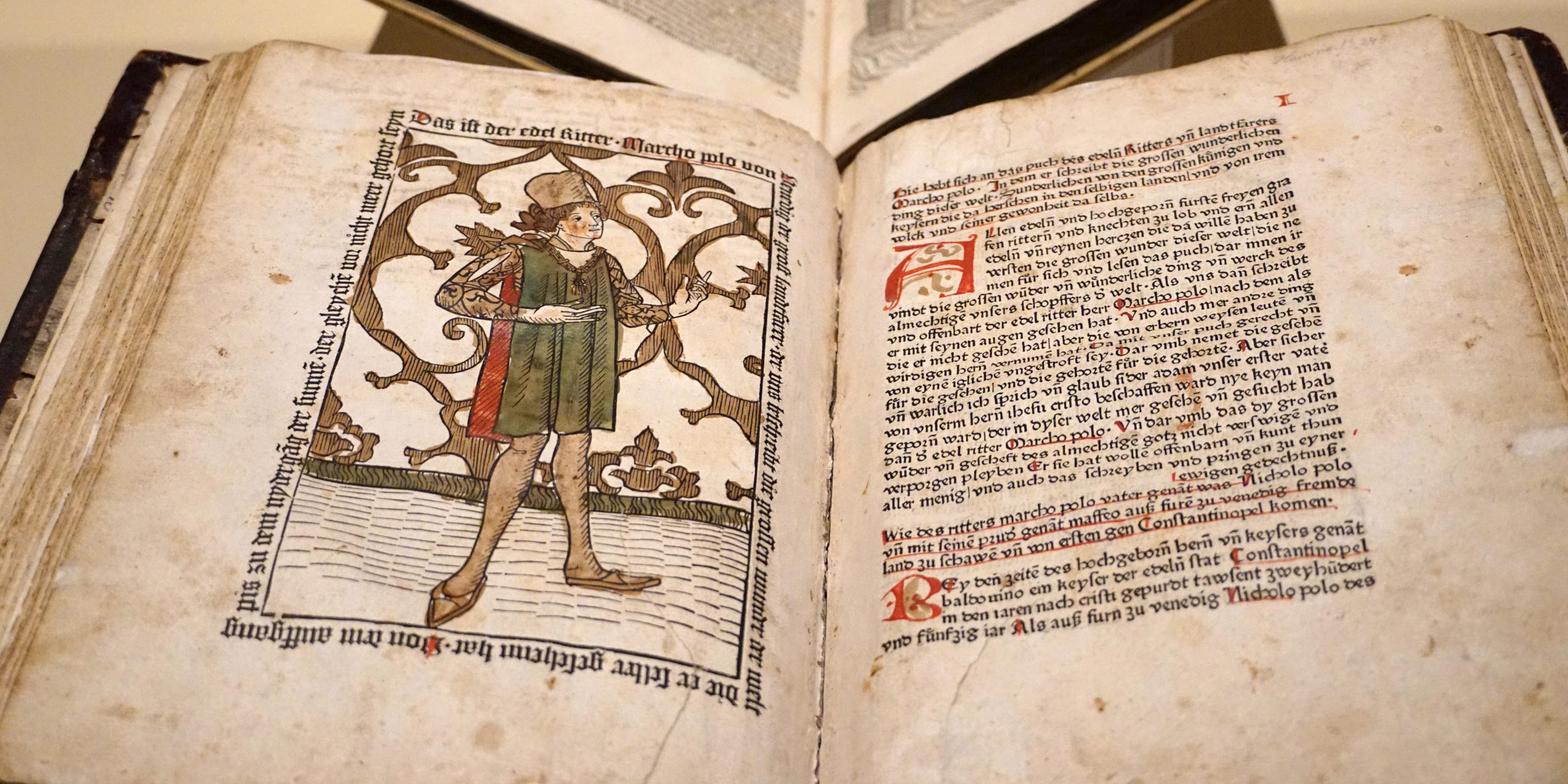

(Header image: A German-language book from the 15th century on display during an exhibition marking the 700th anniversary of Marco Polo’s death, Venice, Italy, April 5, 2024. Andrea Merola/EPA via IC)