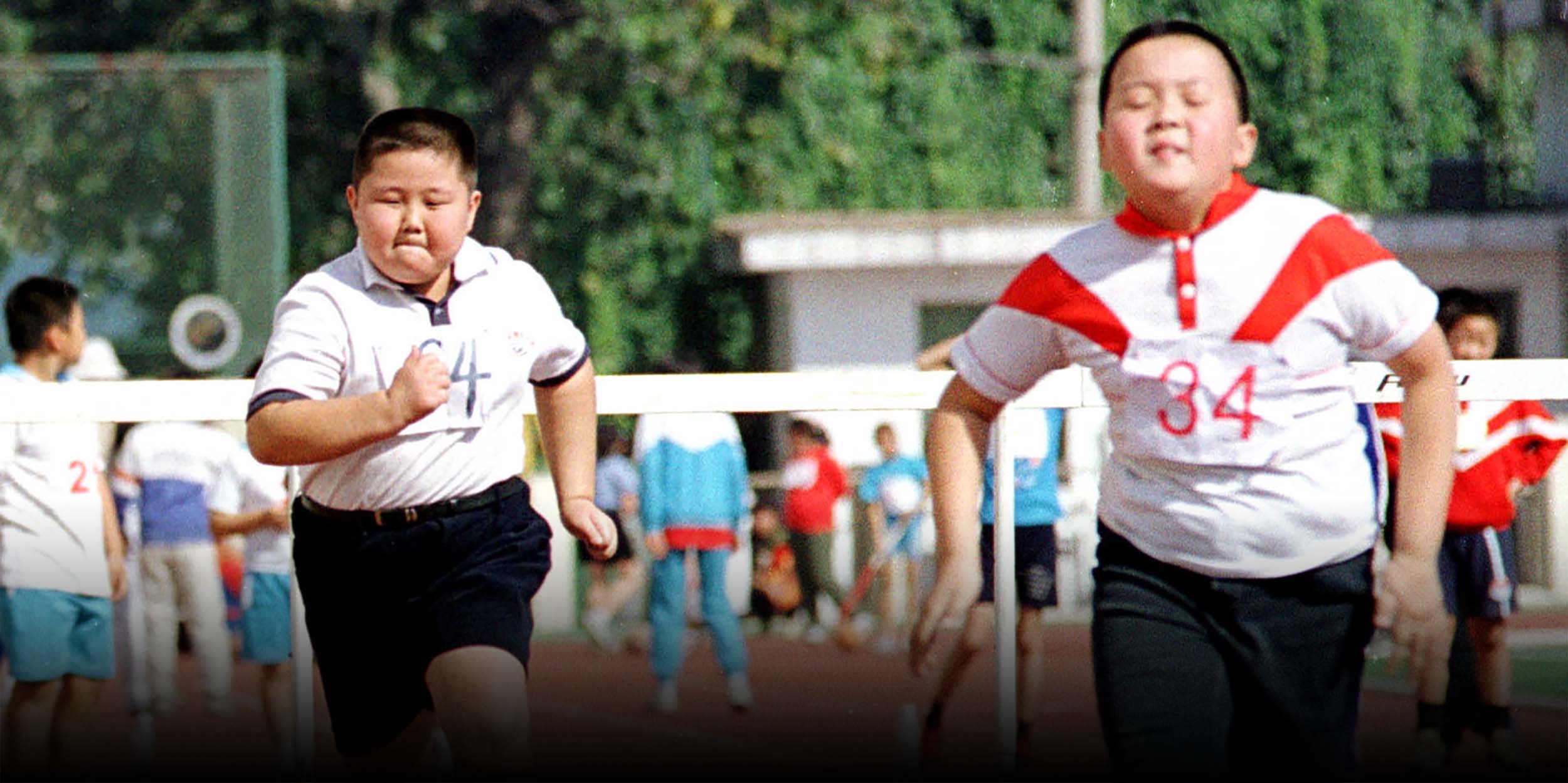

China’s Rural Children Close Height, Weight Gap, but Obesity Looms

Over the past three decades, children in rural China have been rapidly catching up to their urban counterparts in terms of height and weight indices, suggesting a marked improvement in the health and well-being of rural children, a new study shows.

The study also highlights a looming concern: The obesity risk among rural youth is escalating and might soon exceed that of urban areas.

In a paper published Tuesday in the Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, researchers analyzed height and body mass index data of over 310,000 Chinese students, and also highlighted differences between urban and rural regions. The collaborative project comprised seven institutions including Peking University, the University of Melbourne, and Tsinghua University.

Amid China’s declining fertility rate and rapidly aging society, the health and physical development of its children and adolescents have become areas of increasing concern. Height and BMI indices are recognized as crucial indicators of human capital.

Children who are notably short, often due to stunting, tend to face health and education issues, which can lead to lower incomes in adulthood. Furthermore, children and teens with a high BMI, indicating obesity, face a greater risk of heart issues in their later years.

BMI is a health indicator based on weight and height. It is calculated by dividing weight by the height squared. A BMI between 24 and 27.9 is categorized as overweight, while a BMI over 28 is considered obese.

The Lancet study highlights that between 1985 and 2019, the BMIs of children and adolescents in rural and urban China has risen. Specifically, for 12-year-olds, boys in urban areas had their median BMI go up by 3.3 kilograms per square meter, while for girls it rose by 2.6 kilograms per square meter. In contrast, rural boys experienced a BMI increase of 2.8 kilograms per square meter, and for girls, it was 2.4 kilograms per square meter.

Researchers found that between 1985 and 2005, urban children in China had significantly higher BMIs than their rural counterparts, which was attributed to the rapid development of China’s cities. However, after 2005, the BMI gap between urban and rural areas started narrowing.

“This may reflect the fast urbanization of rural China and the convergence of lifestyles,” the researchers noted. “Given the increase in overweight and obesity in the countryside, we expect that such risks for rural children may fully catch up with or even surpass those in the cities.”

According to the Lancet study, previous data has shown that instead of malnutrition, being overweight is now the leading issue across the country. In the last 20 years, the number of overweight and obese children aged 7-18 has risen nearly fourfold from 5.3% to 20.5%.

The rise in childhood obesity has largely been linked to shifts in eating habits, with increased consumption of wheat, fast foods, and sugary drinks a factor, the study stated. Additionally, today’s children and teenagers are less active and spend considerably more time in front of screens, further impacting their overall health.

While obesity concerns loom large, there’s also been significant focus on height disparities in China. Urban children have consistently been taller than their rural counterparts.

However, data from 2019 shows the gap is narrowing, according to the study. Over the past thirty years, 12-year-old boys and girls in rural areas have seen increases in median height by 15 centimeters and 12 centimeters, respectively.

A separate study published in the American Journal of Human Biology found that among 18-year-olds in China, the height disparity between urban and rural males is diminishing. For females, however, the trend was only seen in the eastern areas, suggesting regional inequalities.

This study, conducted by researchers from Xinjiang Normal University and Changji University, and funded by the National Foundation of Philosophy and Social Sciences, suggests that this inequality might be rooted in longstanding patriarchal beliefs.

“In China, a greater importance attached to males is more prevalent in poor rural areas, where parents are more inclined to prioritize resources for boys rather than girls,” this study suggests. “This factor may contribute to the fact that rural girls from impoverished areas lag behind their urban male counterparts.”

On height indicators, the Lancet report underscores economic disparity. It points out that rural families often have lower incomes and fewer opportunities to access quality health care. This limited access makes it harder for rural children to reach their potential adult height.

The Lancet study’s authors emphasized the need for more nuanced policies to prioritize the health of rural children. They also advocated for both improved nutrition and increased physical activity to counteract the dual challenges of obesity.

Editor: Apurva.

(Header image: IC)