For China’s Mothers, Big Tech Can Be a Burden

“Online parent-teacher groups are my ‘pain points,’” Yun explained. “I’m in dozens of online parent-teacher groups. Whenever my children enroll in an extracurricular activity, I have to join a parent-teacher group (for that activity).”

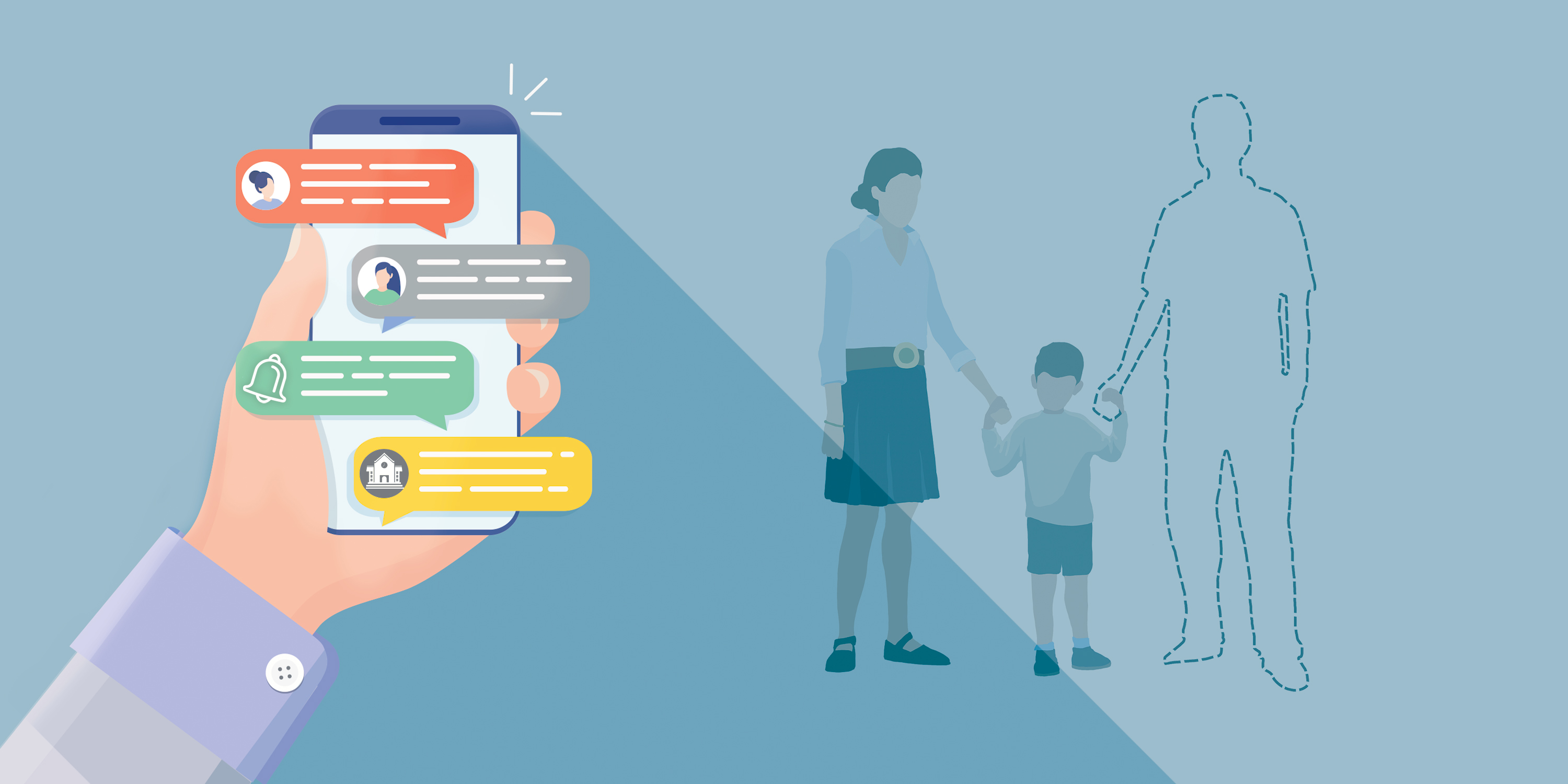

“My husband never joins these groups. We have a clear division of labor on this. I am responsible for all online communication with teachers.”

My research team and I interviewed Yun in 2022, part of a three-year investigation of parenting practices in Shenzhen, the coastal city of Xiamen, and Tai’an, in the eastern province of Shandong. One of the things that struck me was just how deeply digital technology has become intertwined with parenting. While physical care, emotional care, and child discipline continue to make up the bulk of parental duties, the penetration of digital technologies and media into the daily lives of Chinese parents is generating a new form of parenting.

Like previous forms of domestic labor, digital parenting is a gendered activity. Although technology is stereotypically regarded as a masculine domain, with men perceived as uniquely skilled at using digital technologies, my interviews suggest this norm doesn’t carry over into the parenting realm. Yun’s experience is representative: As parenting shifts online, mothers are being asked to do more, not less.

For example, mothers are more proactive than fathers in searching for, filtering, and sharing parenting information online. They subscribe to parenting blogs, join parenting fora or chat groups, and search for childrearing information on Baidu and the Instagram-like Xiaohongshu.

The mothers I interviewed found online child care information helpful in solving specific problems in their lives and in boosting their overall knowledge of childrearing practices. Mei, a mother in Tai’an, told us: “They (parenting blogs) change your mindset when it comes to child care.”

Another characteristic of digital parenting is the necessity of staying in constant communication with teachers. Parent-teacher groups on messaging apps like WeChat or QQ are common. For the mothers of school-aged children I interviewed, checking their messages in these parent-teacher groups had become a daily task: a way of getting updates on their children and keeping abreast of homework and school activities.

Fang, a mother in Shenzhen, detailed her routine: “I am responsible for maintaining contact with teachers. We have a parent-teacher group, and teachers post exam information and comments on students’ performance in the group. I also actively contact the teachers outside the group to ask them about my son’s performance.”

Many mothers in my study reported collaborating with teachers on numerous tasks related to their children’s education. “In the parent-teacher WeChat or QQ groups, we receive notices all the time, telling us to work with teachers to educate our children at home, sign some forms sent by the school, or pay fees online,” Fang explained. “I need to pay a lot of attention to it. It takes up my time.”

Another, often overlooked aspect of digital parenting is online shopping. Although digital marketplaces can be convenient, the mothers we spoke to spent a lot of time selecting high-quality products for their children. Before making a purchase, they might compare the prices of various options, evaluate the reliability and reputations of online shops, and read through consumer reviews.

Fathers, on the other hand, seldom engage in any of this labor. For example, Mei’s husband “never reads (parenting information online).” Many fathers in my study defined aspects of online parenting such as searching for childrearing tips or online shopping as “feminine interests” and assumed that their wives enjoyed performing these chores. As men, fathers emphasized their work responsibilities to excuse their limited involvement in digital parenting. Qiang, a father in the southeastern city of Xiamen, explained: “Their mother has more leisure time. She visits parenting fora or joins mom groups online. She cares more about this kind of information. I seldom look for child care information because I am busy with work.”

Many fathers likened their status in online parent-teacher groups to “lurking.” Mothers, fathers, and teachers all seemed to agree that it was more appropriate for mothers to manage online communication with the school. (Teaching is itself a highly gendered profession in China, especially at the kindergarten and elementary levels.) Some fathers defended their lack of engagement by stressing the role of mothers as a liaison between family and schools. “Any communications with teachers are handled by my wife,” said Dong, a father in Shenzhen. “She uses WeChat and QQ to chat with teachers. If necessary, she’ll call them. I seldom get involved.”

While mothers, fathers, and even teachers referenced gendered stereotypes of mothers as the primary caregivers and fathers as breadwinners to explain the gendered nature of digital parenting, we found the rise of this new form of labor may actually be deepening the gendered division of labor within households. By blurring the boundaries between child care, work, and entertainment, digital technology renders the work mothers put into child care even more invisible and allows husbands to write off their wives’ labor as easy, even enjoyable.

Few fathers acknowledged the possibility that their wives might be under increased pressure due to the need to constantly respond to new information and messages related to their children’s care. In contrast to stereotypes about digital liberation, digital parenting calls attention to the role technology can play in oppressing and exploiting women.

Editors: Cai Yiwen and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: Visual elements from Malte Mueller, drogatnev and pascreative/VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)