How Liang Qichao Rewrote China’s Future

This year marks the 150th anniversary of Liang Qichao’s birth. One of the most important reformers of the late-imperial and early Republican periods, Liang was born in Guangdong on China’s southern coastline on Feb. 23, 1873. In 1895, after the Qing regime’s disastrous defeat in the Sino-Japanese War, a 22-year-old Liang and his teacher Kang Youwei initiated a program of reform and modernization with their “Scholar’s Petition to the Throne.” In 1898, Liang and Kang helped kickstart the so-called Hundred Days’ Reform period before a conservative coup drove them from the capital and into exile. Over the next several decades, until his death in 1929, Liang helped pioneer China’s “New Culture” movement, founding newspapers and magazines that advocated for a radical break from traditional norms, translating political tracts, and lecturing at top universities.

Official biographies of Liang usually leave off there. Less discussed is his interest in literature, and especially speculative fiction. Liang not only translated Jules Verne’s “Two Years’ Vacation” into Chinese; he also wrote “The Future of New China,” recognized as the first work of Chinese science fiction. Unlike his reformist peers, many of whom attended missionary schools or were educated overseas, Liang received a purely Confucian education and entered politics through the traditional imperial examination system. So, how did a disciple of Confucius become China’s earliest proponent of science fiction?

It starts with Liang’s unorthodox opinion of fiction. In traditional Chinese culture, fiction was not considered a serious literary genre. Officials and intellectual elites instead emphasized the role of poetry and non-fiction in educating people. Liang held a different view. In his “On the Relationship Between Fiction and Governance,” he stated that fiction “dominates humanity” and described its effect on readers as “smoking, soaking, piercing, and uplifting” them.

In more modern terms, fiction immerses the reader in another world, pierces them with strong emotions to trigger empathy, then allows the reader to relate to characters on a spiritual level. Liang believed this extraordinary power made fiction the best tool for reshaping the hearts of people both cognitively and affectively, a prerequisite for transforming the spirit of a country.

In 1902, Liang put this theory to the test by launching New Fictions magazine. He was interested neither in realistic sagas nor in the mythic or romantic novels popular at the time. “To create a new heart and identity, one must create a new fiction,” Liang wrote. He wanted a fiction that was more just fiction, and so he turned his attention to science, technology, and metaphysical contemplation — all subjects that more or less owed debts to Western modernity.

In the inaugural issue of New Fictions, he proposed concepts such as “scientific novels” and “philosophical novels.” What theme could be more suitable than science fiction? The magazine published the first Chinese translation of “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea” as the “scientific novel” “Underwater Journey.” “Omega: The Last Days of the World,” a future-set tale by French astronomer Camille Flammarion and translated by Liang from the Japanese, was likewise advertised as a “philosophical novel.”

But the most striking piece published in New Fictions was Liang’s own “The Future of New China,” which imagines the world in the year 2513 of the Confucian Era — A.D. 1962. In this world, “New China” has already achieved institutional reforms, its technology is highly developed, and the country has leaped ahead to become a world power.

The academic Leo Oufan Lee has argued the significance of this story lies in the way it introduces the concept of futurity into the Chinese context. Prior to this, the sense of time in Chinese classical literature was often vague: A hundred years might pass by in a snap, and history was constantly recurring. But “The Future of New China” invited readers to look 60 years ahead and imagine how that time might transform institutions, technology, and culture.

Adding a new dimension of time to literature fit with Liang’s political beliefs, most notably his desire to replace the traditional imperial chronology with what he called a “Confucian chronology” starting from the birth of Confucius. At the same time, although “The Future of New China” imagines a technologically advanced China, it does not present many of these advances in detail. This also reflects a core view of Liang’s about science fiction: What is important is not fantasies of technological advancement, but the transmission of scientific concepts and the promotion of scientific education. Similar ideas informed his translations. For example, when translating Verne’s novel “Two Years’ Vacation,” Liang omitted technical details in favor of highlighting what shaped the characters, and what would move people. In Liang’s view, new people — those who had undergone a baptism of science — and not new technologies, were the real protagonists of science fiction.

That’s not to say Liang didn’t pay attention to technological progress and its impact on people. In 1903, while in exile overseas, he went on a trip to North America, where he lamented the high division of labor in production. In his account of that trip, “Journey to the New World,” he wrote of needle workers: “The one who sharpens the tip does not know how to make the eye, and the one who makes the eye does not know how to make the tip. Moreover, work beyond the needle is irrelevant, and any other undertaking and ideal beyond the work no longer matters.”

Liang was neither a hopeless futurist nor a technocrat. He was quick to grasp the alienation of workers in a modern capitalist industrial society. The division of labor left workers indifferent to other undertakings, which was clearly not what he had in mind for his ideal society. He believed the Chinese people — the entire human race, for that matter — should prepare for the development of science and technology, but not blindly pursue it. People must maintain their ideals and pursue spiritual fulfilment, or else become mere cogs in a huge machine.

Liang’s science fiction career did not last long. He spent his years in exile traveling widely, publishing new writings and promoting domestic reform. After the founding of the Republic of China in 1912 (coincidentally the year Liang picked for the birth of “New China” in “The Future of New China”), he held important positions in the new government, including minister of finance.

Some researchers argue Liang simply no longer had time to dabble in sci-fi. Others believe the lackluster technology of China at the time limited the imagination of its writers. That misses the mark. As many members of the rising generation of Chinese science fiction writers have realized, a heavily industrialized landscape can make writing science fiction harder, not easier. It thrusts writers into a crowded field where they must compete to see who can come up with the most novel technologies and the grandest industrial wonders — see the ongoing debate over whether science fiction should emphasize “science” or “fiction,” for example — while making it harder to interrogate the relationship between technology and people or how the former fundamentally reshapes our cognitive and affective landscapes.

Liang’s primary intention was not to predict. For him, science fiction was a means of personal healing, a way to grasp for a path in the darkness around him. His goal, similar to the thinkers of ancient China, was “to carry the Dao through literature.” Science fiction was only meaningful if it conveyed “the Dao”; he believed it could change people’s minds because it happened to him first.

Some modern authors are picking up on that tradition. No longer surrendering their imaginations to the future, they’re beginning to turn back to Liang’s time. Perhaps an era where modern science and culture had not yet been defined offers more to get excited about than one where industrial wonders have gradually become reality.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misidentified the Jules Verne story translated by Liang.

Translator: Matt Turner; editor: Cai Yineng.

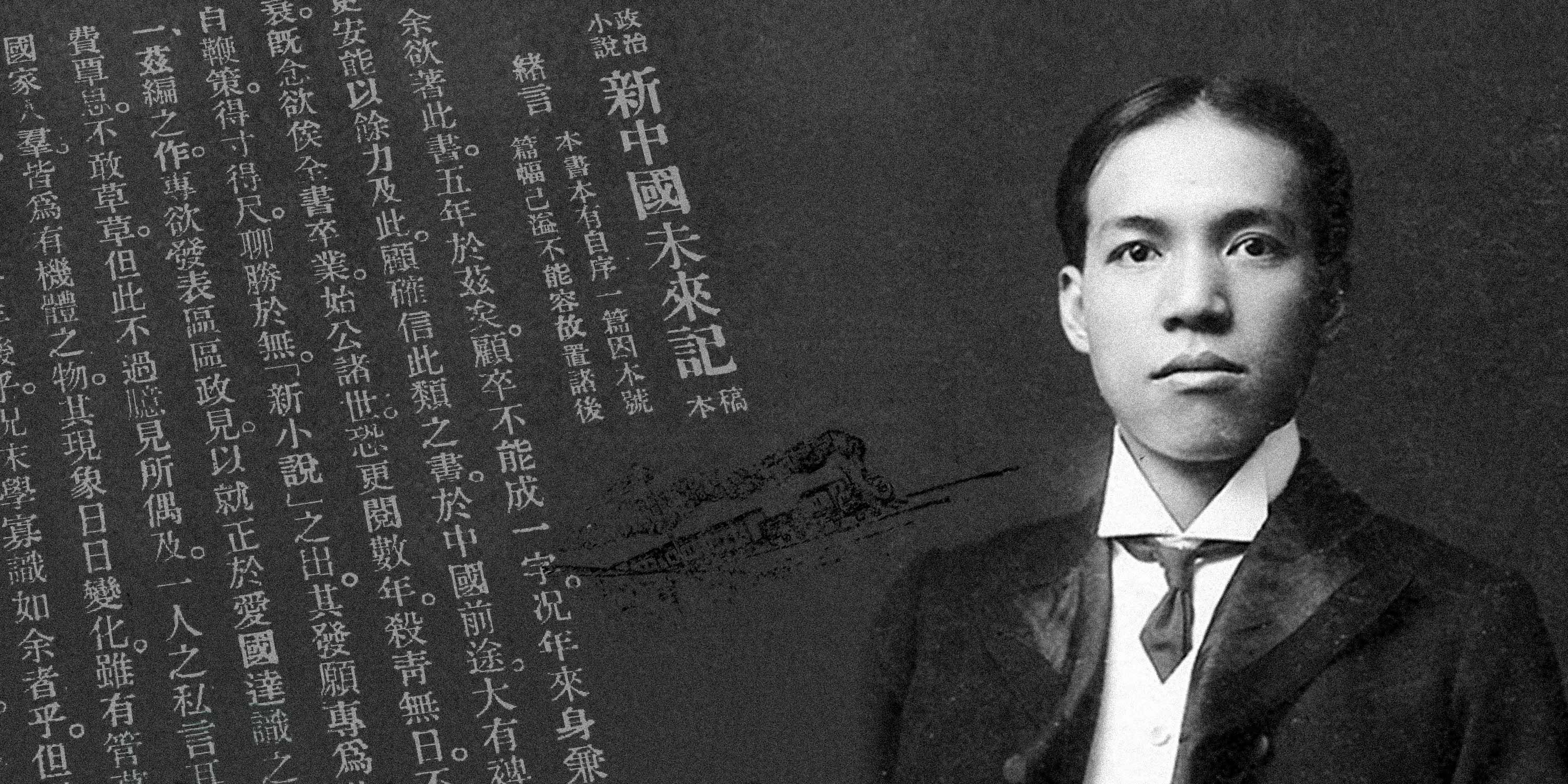

(Header image: Liang Qichao in Japan. From Wikipedia)