Wu Zetian and the Quest for Feminism in All the Wrong Places

In all of Chinese history, only one woman has ruled in her own name as empress regnant. From A.D. 665, when she and her husband the Emperor Gaozong effectively took joint control of the imperial court, until her death in 705, Wu Zetian dominated an empire of over 50 million, oversaw the rise of a number of powerful women, such as her adviser Shangguan Wan’er and her daughter the Princess Taiping, and nearly established a dynasty all her own.

But was she a feminist? The question may appear odd, even faintly ridiculous, but in part due to the lack of other viable options, some modern Chinese feminists have sought to reclaim Wu Zetian’s legacy from the politically motivated attacks of male historians and position her as a trailblazer in the field of women’s rights.

If we apply only the most superficial definition of the Chinese word for feminism, nüquan, which when written is composed of the words for “woman” and “power” or “rights,” she may even have a case. Wu Zetian wielded the highest power possible in China, and at no other point in ancient Chinese history were so many women involved in the upper reaches of politics — a legacy that outlasted Wu only to die when her grandson, Li Longji, eliminated Shangguan Wan’er in a coup in 710 and wiped out the Princess Taiping’s entire family three years later.

Li — who later ruled as Emperor Xuanzong — proudly proclaimed that, in keeping with the teachings of the Confucian canon, he had done his duty to root out any women who dared to manipulate national politics and thereby eradicated a hidden threat to the stability of the empire.

While it’s tempting to indulge in what ifs, modern-day attempts to restore Wu Zetian’s reputation as a powerful, capable woman who might have set China on a different course are fundamentally misguided. Inevitable distortions aside, the historical record is clear: Wu Zetian not only didn’t work for female emancipation, but she also sought to de-feminize herself, almost as if she preferred people forget she was a woman altogether.

Wu Zetian was of humble stock, born in 624 to a merchant family of the early Tang dynasty (618-907). Although considered a Chinese dynasty, the Tang’s rulers were the product of hundreds of years of co-mingling between Han Chinese and nomadic Hu tribesmen to China’s north. They identified with the dominant Confucian culture of the earlier Qin (221-206 B.C.) and Han dynasties (221 B.C.-A.D. 220), but their mentalities and lifestyles were heavily influenced by Hu culture, including the less tightly regimented gender norms of life on the steppe.

This brief relaxation of Chinese society’s oppression of women offered Wu Zetian the window she needed, but even in the context of the Tang, her rise to power was still conditioned on her ability to bear sons. Wu gave birth six times; five of her children, including four sons and a daughter, made it to adulthood.

Her status as the mother of four potential imperial heirs would prove crucial in the palace battles to come, but Wu did not coddle her offspring. In their vicious fights over the future of the empire, Wu subjected her five surviving children and their various partners and children to violent torture. There was nothing sacred about their relationship, no maternal bond — merely fear, obedience, paranoia, and self-preservation.

Although hardly exempt from her mother’s cruelty, histories from the early post-Tang period suggest that Princess Taiping was able to earn the empress’s respect. The most politically astute of her siblings — at least among those who survived Wu’s punishments — an 11th century history records that, “The Taiping Princess had a sensitive grasp of political strategy that led her mother to view her as an equal. As a result, she received a love that Wu’s other children didn’t, and the two on occasion conspired together.”

Or perhaps simply Wu didn’t see the Princess as a viable enough successor to be a threat. The empress wasn’t interested in legitimizing the rule of another woman. To maintain the favour of her court ministers, she intended to uphold the tradition whereby only male kin could become emperor.

Throughout her reign, Wu Zetian took great pains to appear nonthreatening to China’s patriarchal order. As part of her plan to replace the Tang dynasty with a separate Zhou dynasty, she legitimized her rule by authorizing the fabrication of Buddhist texts. For example, the main gist of the “Addendum to the Great Cloud Sutra” was that a “celestial woman of purity and light,” an incarnation of the future Buddha Maitreya, needed to descend to earth and take control of the Tang imperial court. Although she may be ruling in a woman’s body, the revisions emphasized that in essence she was a sexless incarnation of Buddha: “The Bodhisattva has no fixed form: for the salvation of those on Earth, they can assume any form, such as the woman who walks among you today.”

The main purpose of this text was to efface Wu Zetian’s sexual characteristics; the “Addendum,” which paved the way for her ascension of the throne, became a bible of sorts for this female emperor’s rule. She ordered every prefecture to build at least one Great Cloud Temple, and each temple had to house a copy of the Addendum, from which the high priest would regularly read to inform the masses that the “Emperor is not a woman, but a deity.” (Remnants of these temples can still be found in modern-day Kyrgyzstan.)

More broadly, while it’s true that Wu personally appointed a fleet of cultivated and capable women to serve in the palace and allowed them to exert influence that far exceeded the moral limitations imposed on women by Confucianism, she didn’t open the civil service examination system or the official recommendation system up to women.

In fact, not a single policy or measure was adopted during Wu Zetian’s rule to encourage regular women to challenge the rules of patriarchal society. In all the years that historians have studied Wu Zetian, the only vaguely feminist decree they could find from her time in power was one that extended the period during which children must mourn their deceased mothers. According to this decree, offspring had to resign from their jobs and keep watch over their mother’s grave for three years, the same duration as for deceased fathers. However, rather than “women’s rights,” it would perhaps be more apt to say the decree was a matter of “mothers’ rights” — the same mothers’ rights that facilitated Wu’s rise.

If Wu Zetian wanted to avoid precipitating a cultural and political crisis, it didn’t work. Her reign became a rallying point for the patriarchal society then in eclipse. From Li Longji onward, Chinese political factions committed themselves to tearing down her legacy, sullying her reputation through virulent criticism of her character, morals, and political achievements, and reinforcing the separation of the sexes. This didn’t prevent the subsequent emergence of several more prominent female political figures, but no woman again dared claim the throne for herself.

Expecting Wu Zetian to conform to the expectations of modern feminism is futile. That doesn’t change the fact that the reign of China’s only true female sovereign did nothing to challenge sexual inequality in China. If feminism is a movement by all, for all, Wu Zetian’s achievements belonged to her and her alone.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

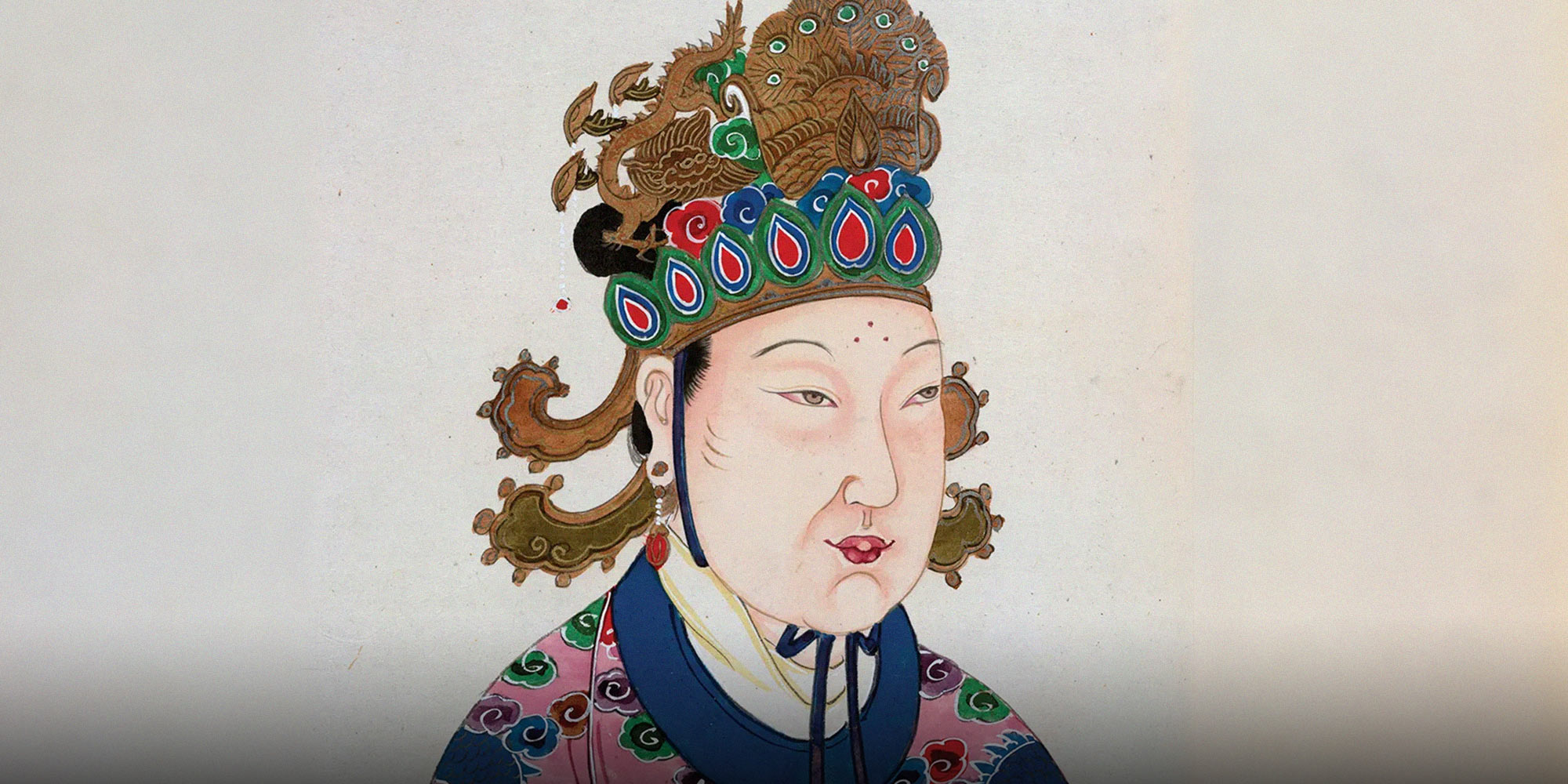

(Header image: A portrait of Wu Zetian from the 18th century. From The British Library/Robana Picture Library)