The Art of Butchering

It must be a January afternoon, when I was in the sixth grade. I come home from school. The air in our shack smells sinister. It’s spookily quiet, too. I go to check up on Piggy in the backyard. There’s no sight of its white haunch in the pen, only the straw bed I made for it to fend off the snowy winter in the northern Hunan Province. The dunghill at the far corner looked stale and dark green. You judge if the dung is fresh by its color and moisture. The inevitable had happened.

Piggy was raised to be slaughtered for the Lunar New Year. But that part had somehow slipped my mind. Our first pig, growing up in Hunan Province, was when I was about three, before I had any memory. The year before we had Piggy, we had our second piglet for a brief month. It got very sick and turned orange, and nobody wanted to buy it. Some family friends gave it to me as a plaything. Mom nursed it back to a healthy white with a cocktail of human medicines. Then just when it got better, it died of rat poison. I can still remember its tiny body, frothing on the floor. We pretty much kept it free-range, walking it in the woods like a pet during weekends. I guess that led to the accident. Perhaps that was why Mom built a pen for Piggy.

My parents hadn’t told me that they were going to kill Piggy that day. I don’t know if it was to spare my feelings. I suppose not. After all, I was twelve. I don’t think feelings about a hog counted much. Not to my Sichuanese parents.

The previous spring Mom and a neighbor from Yunnan bought a pair of piglets from a street vendor on a whim. We got the one that was shorter. Piggy was not afraid of kids, so we all treasured it almost like a pet. No kid in the brick and tile factory had a pet. We were lucky just not to be hungry. Piggy was neutered before we had it. I was too young to figure out whether it used to be a boar or a sow.

I realized where Piggy might be. I raced to our new apartment in the workers’ living quarters, which occupied a large corner of the enclosed factory. My heart was aching, and my insides seemed hollow. It felt like the time I cut my foot on a clamshell.

The door of our new place was left open. The outer room smelled of lard and chitlins. I don’t remember anyone in the room with me. Perhaps I was in shock and failed to notice. On the pinewood dinner table spread Piggy’s glistening body parts to cool off, no longer recognizable. At the center was Piggy’s severed head, eyes shut, mouth agape, tongue missing, and snout pierced. Next to the head flopped the spotty, bubbly lungs, the shiny membrane withered and the marble tubes bloodied. In a basin rested the heart, the purple liver, and the coiled tail. In a tin pot were piled the rich leaf fat and the lacy caul fat. In a bamboo basket were the tripe and bladder, insides turned out, and a heap of intestines.

I went to the yard in front of the nearby workers’ canteen. There were puddles of coagulated blood. Over the years, I had watched countless hogs being butchered right here, with savage fascination. I knew the procedures all too well. I imagined Piggy’s blood gushing out of an obscene cut, dealt by the butcher with a sharp-pointed knife before they set about to give it a hot bath. Its first and last bath. Piggy must be so terrified, manhandled by strangers and my father. Its blood must have been curdled, literally, into an affordable, delicious treat.

That night, Mom estimated that our hog weighed at least three hundred and fifty catties. Apparently, that was very impressive, at least a hundred catties heavier than Piggy’s sibling, butchered prematurely due to some kind of liver disease.

“It was a big fat hog. It has repaid its debt,” Mom said repeatedly.

I could not find words yet.

Mom consoled, “You know, when I was a girl in the 70s, a two-year-old pig weighing about a hundred catties would be considered a fat hog. We humans barely had enough to eat. In those days, even a pig could enjoy longevity.”

Pretty quickly, pride usurped my sorrow, whenever I would boast about the great hog that we had raised in Hunan back in 1997. For nearly eight months that year, Dad and I combed Piggy’s armpits, neck, and the back of its ears, while it lay on its flank, baring its tender-most parts with trust. Piggy’s fattening body never impaired its piglet cuteness, not even, or especially, when it broke out of the pen to furrow tubers under the redwood trees. This happened countless times. Only Dad could coax it back to its pen. Piggy was very smart.

These fond memories didn’t stop us from enjoying its cured flesh for the following seven months, before I returned to Chongqing to attend middle school.

That is how we see our meat. No matter what affection we might have for our livestock and fowl while they are alive, food is food. We care for their well-being — Mom even shares their daily lives as part of the family — but of course, only until the day when we harvest their flesh, blood, and bone marrow. We tend not to reflect on taking animal lives, with perhaps the exception of the Buddhists; traditionally, animal rights are not an issue.

We eat not only livestock but also pets and exotic species. For centuries, it appears that foreign visitors have been condemning our practice of eating dogs, not just from the market, but also guard dogs. Of course, some would argue that the ordinary yellow country dog is not a pet. In the late aughts, I met not a few white European students who, within the first month after they landed in Beijing, had checked the top Chinese experiences off their bucket list: hiking to the Great Wall at Badaling, snapping photos of the pandas at the Beijing Zoo, and seeking out dog restaurants. To their inconvenience, the 2008 Olympics drove the shady eateries underground.

In the summer of 2012, for the first time in fourteen years, I returned to the Hunanese village where I grew up, for a short stay in the factory where we raised and ate Piggy. Two of my uncles still worked there. My fifth uncle was invited to a family banquet, and I was brought along. The banquet was occasioned to have a taste of “Dutch pig” — or, as its known in English, guinea pig. It was quite a surprise when I found out it was more rodent than porker.

It’s not as though the Hunanese don’t eat rats — they do. I remember in the late 90s, there was a fad for securing houses with steel wires that electrocute the nocturnal vermin. A rat trips on the wire trap, raising a caterwauling alarm, hence the contraption’s name: the Electrical Cat. Often the rat-hunters couldn’t finish one night’s kill, so they would preserve the skinned, quail-like rodent, like hams for winter. The Hunanese love to cure all kinds of meats — pork, fish, fowl, you name it. It’s a signature of their cuisine.

On our motorbike ride to the banquet, I overheard my uncle’s phone conversation with his friend, which left me with the impression that a Dutch pig was as curious as dragon flesh. Upon arriving at a riverbank house, we were invited to the table without fuss. The host told me that the centerpiece used to be some kid’s pets, now chopped up, browned, darkened with soy sauce, and small-fried with green chili, innocuous and innocent like your everyday chicken. Two Dutch pigs did not yield much meat, all brittle bones and shriveled skin. It tasted no different from house rat, a chewy, gamey flavor — unremarkable, to say the least. I found myself attacking the yellow catfish dry pot more. Indeed, the yellow catfish has since become popular nationwide.

Perhaps the right way to handle exotic meats is to incorporate them into your cuisine. Make it less exotic and more palatable. Just like our Sinicization of crayfish. An invasive pest that destroyed paddy fields and dams when I was a kid, now it is the night market chow. Starting from 2017, Germany suffered an ongoing American crayfish invasion. When the tidings finally reached China in 2018, it drove us into a cyber-frenzy. We were practically drooling over the crayfish army landing the German shore. Our solution is openhearted — excuse me, openmouthed: why don’t invite us over to eat them into extinction?

A little over a year after that exotic meat experience, when I was missing home food in Mississippi, I told a Brazilian friend about the small-fried Dutch pig. A true Brazilian that he was, missing home food as much as I did, he didn’t appreciate our ways of chopping up a guinea pig into tiny pieces, smothered in hot chili peppers. To show me the only respectful way to treat guinea pigs, he googled “grilled guinea pigs,” whereupon troves of photos buffered and loaded, featuring racks of grilled rodents with caramelized skin and gaping, toothy mouths.

I was amazed by the size of the carcass, which was much bigger than that in my imagination, because you seldom see an animal whole in Chinese cuisine. Butchering involves dismembering. Every Chinese kid learns that from the fable of butchering a bull in Zhuangzi. The grilled guinea pig somehow looked familiar to me. Weirdly, I didn’t find it appealing.

“That’s the real Brazilian barbecue,” my friend promised, already salivating.

“It looks like a grilled rabbit to me.”

I finally spotted the resemblances. Grilled rabbit was one of my favorite food memories from high school in Chongqing.

“But it’s a guinea pig. Not rabbit.”

“Sorry if I offend you, but the toothy mouth is kind of scary. How can you put it in your mouth?”

“Trust me. It is the best.”

When I started working on my first master’s in 2009 in Beijing, I often had bouts of meat cravings. Student canteen food can do that to you. About twice a year, I would save up and visit the All-You-Can-Eat Brazilian BBQ franchise on the backstreet. It claimed to be authentic. It charged 69 yuan per person, if I remember correctly, double the price of the All-You-Can-Eat Korean BBQ franchise, but with All-You-Can-Drink Brazilian beer. I’m certain the franchise didn’t have grilled guinea pigs on its menu. They advertised with a ram head, and they sold us dog meat. Hucksters.

Of course, eating guinea pigs, unlike the more banal hedgehog or snake, is not for the delectable meat, but the novelty. Besides the flavors, tastes, and mouth-feel, novelty is also part of our gourmand experience. Why else do we eat a bat? Or a civet cat? Or why did we, I should say, until the days of reckoning with pandemics caused by coronaviruses.

Still, normal pigs and birds should suffice. With a rural upbringing in the 90s, I knew that great efforts have been put into fattening up the livestock and fowls. One common practice is castration. The piglets are routinely castrated, as are roosters and some breeds of hens that begrudge eggs. Do the math. A rooster weighs 4 or 5 catties at best, while a capon, free of testosterone and feathering, weighs about 2 catties more — extra chicken on the same bones.

I guess the rationale is that if the livestock and fowls are not preoccupied with sex, they will concentrate on gaining weight. It’s simple behavior control. Your yard is free of cocks fighting over the harem. One rooster per household is quite enough, as roosters are noisy and lecherous. Think about Chanticleer the Cock in “The Nun’s Priest’s Tale.”

Empathetic folks may think neutering a litter of squealing piglets is a delicate art. Think again. In Chongqing, the hog keepers just hire a gelder. The gelder grabs the little boar by its hind legs, steps on its head, inoculates it behind one ear, squeezes its scrotum, applies some disinfectant, and slits the sack open with a sharp blade — out pop the testes, busted and dangling. He chips the balls off in one swift swish and applies the disinfectant again. The entire procedure is finished in less than a minute. A boar becomes a hog.

The ovariectomy of a young sow is more surgical. After securing the gilt with his foot, the gelder finds the spot at its lower abdomen, applies the disinfectant, makes an incision with a scalpel, digs in with his fingers, and snatches off part of the ovaries. The womb is left intact, but its growth is stunted. The atrophied womb is prized by the Cantonese for its al dente mouthfeel. It’s called shengchang, or raw intestines. The squeaky wails are quite unnerving, even more so if you live in the hilly country of Chongqing, what with the reverberations in the hollows.

Tragic for the pigs, but a glorious day for the dogs.

In colloquial Chinese, the language of the Han people, the words for meat (rou) and pig meat (zhurou) are interchangeable. For many ethnic groups, pork is an indisputable staple meat. China produces over half of the world’s pork, but until a few years ago, most hogs were raised in small pig farms or in rural households. For peasants and hoggeries alike, it is always a gamble to raise hogs because of epidemics and price fluctuations. Any porcine epidemic causes an apocalyptic crisis. For instance, PRRSV, or Blue Ear Disease, hit 25 provinces in 2007. Prices fluctuated for about 35 to 37 months, according to a 2022 study.

Pork is so important to our livelihood that it is not an exaggeration to say that the stability of pork price is a matter of national security. America has its oil reserve; China has its pork reserve. In September 2013, a Chinese company acquired the world’s largest hog and pork producer, Smithfield.

Any change in the pork price is deeply felt in my rural hometown in Chongqing. Due to repeated porcine epidemics in recent years, my aunts and cousins’ families have stocked up hundreds of catties of pork in the freezer, which runs against our traditional demand for freshness. When we chatted on the phone, Mom would relay their latest hoarding sprees.

“Pork isn’t the only meat out there,” I’d say.

“But one’s got to eat meat.”

“You can have fish or chicken. They are better for your heart.”

“Your dad has a renal problem. The doctor advised him not to eat seafood or tofu. And, how can anybody live without meat?”

I grew up in the countryside of Hunan and Chongqing. Both regions were leading pork producers in the age of household pigpens. It’s no surprise then that both regions are well known for their distinctive styles of cured pork. The differences are apparent when it comes to the cuts, which reflect the respective regional cuisines. This insight was driven home to me when, after a year studying in Mississippi back in 2013, I could not find a proper cut to make twice-cooked pork because bacon is the standard use of that part of the pig there. You’ll have to visit the Asian market and buy in bulk.

I remember in the 90s, the Hunanese villagers would walk all the way to the butcher’s stand at the water-gate market for 100 grams of lean meat with a tiny bit of fat. The pork was sliced into morsels for a green chili stir-fry, now nationally famous as “small-fried pork,” served in medium shallow bowls. When dismembering the hog, a Hunanese butcher must keep these cooking methods in mind.

The Sichuanese migrant workers in the factory laughed at the dish on a Hunanese table, “How can you properly enjoy pork like that!”

We in Chongqing serve in large pots, even enamel basins. Lately, cyber-famous Chongqing restaurants in Shenzhen serve in plates or bamboo pans the size of a tea table.

For someone from the southwestern provinces, Hunanese butchery is much too dainty. As the terrains roll westward, the mountains are higher, the valleys are deeper, and the cuts of pork are rougher. In Chongqing and Sichuan, the cut of a New Year Hog is about double-palm wide, each chunk with skin, fat, lean meat, and bones, as it comes. If you set out to cut a kilo of pork at the butcher’s, you will end up with at least two. A Chongqing butcher would always cut more generously, and he’d always surreptitiously dump you a hidden bone or two. That’s why we serve in pots at home, and the twice-cooked pork turns into thrice-reheated leftovers. And we say, reheated leftovers, fully flavored, taste even better. The cut in some regions in Yunnan Province is even bolder. I remember our Yunnanese neighbors quartered their Year Hogs, making sure that no chunk is without a ham. They preserve and smoke their pork that way. Boy, it was a sight on their roofs.

It appears that we don’t believe in killing livestock in secret. It is cruel and gruesome to watch, but isn’t this openness a kind of celebration of hard work? Symbolically, children are acculturated to appreciate every grain in their bowls, but perhaps they aren’t educated about the meat. Some unknown peasants or hog farmers have cared and labored for it, and the livestock and fowl sacrificed themselves (albeit unwillingly) to satisfy the appetites of our mouths and bellies. If we are not mindful of it, then we are ignorant of our bodily karma, that we owe our sustenance to other beings.

When I was doing my doctorate, there was a woman from Hong Kong in our office who claimed that she had never eaten frog. How can you eat an ugly, slimy frog? Then one day, when we stumbled into an authentic Hunanese restaurant under the University of Hong Kong campus, she ordered a field chicken dry pot.

Perplexed, I asked, “But you said you don't eat the frog.”

“Where’s the frog on the menu? I’m ordering field chicken. I love it.”

“What do you think the field chicken is?”

“A kind of chicken?”

“No. That’s a frog. Or American bullfrog, to be exact.”

“What? I didn’t know that.”

“Have you ever thought what it was when you ate it before?”

“No. My mom always bought it from the wet market. I’ve never seen a live one.”

Well, in any case, we enjoyed that field chicken dry pot. In Cantonese, they prefer to call frogs field chicken. Perhaps because they taste similar?

In the first year that my family moved back to Chongqing, Mom used to collect swill for the hogs. She had to climb a foothill to reach the residential neighborhood. Occasionally, during the weekends, I offered to help her. Even though I didn’t have the shoulders for it, I’d carry the buckets on a bamboo pole and hoist them to the rows of mud huts on the hilltop. I’d pour out the clear water in the hogwash buckets, saving the sediment. The sour stench, the coagulated grease, and the increasing weight on my shoulders were all worth it because our hogs were going to be fat and delicious.

But I no longer had a relationship with the hogs like with Piggy.

In Chongqing, we slaughter our hogs differently from the Hunanese. No other event is more important than slaughtering the Year Hog, which announces the start of the Lunar New Year celebration in many rural regions. Usually, we pick a day in Layue, the final month of the Lunar Year, which gives the name to our cured and smoked pork, larou. The slaughter takes an entire morning, ending with a feast at noon.

On the day of the slaughter, we dig a fire pit off the yard to set up a 36-inch wok. When the butcher is taking a breath from the trek with a pack of cigarettes, we get water boiling in the wok. Having rested, the butcher applies his knives to the whetstone, a signal that the relatives should get the hog in the pen. The hog squeaks with terror, probably knowing that something terrible is happening. Once the hog is manhandled and secured by several men on a slab of stone, the butcher stabs its carotid artery decisively. No relish whatsoever. The blood gushes out horridly into a large aluminum basin placed under the stone for that purpose.

The uncanny aspect is that the wailing quiets down to grunts, and then to gasps fairly rapidly, as if the hog has been waiting for the better half of a year for that stabbing. Finally, there it comes. If a hog is fat and healthy, it has “repaid its debt” for the peasant’s feed and care; such is the relationship between the peasants and their livestock.

It seems to take ages for the hog to bleed out. Then the butcher and his assistants drag its unresisting carcass onto the banana leaves spread by the wok, usually the same one that cooked its feed. There, the hog is lathered with hot water to soften its bristles for a clean shave. The bristles flush with the dirty water back into the wok. Meanwhile, Mom is curdling the blood.

In Chongqing, like other rural regions, slaughtering the Year Hog is a reunion for relatives, known as the Feast of the Hog Shaving Soup in dialect, referring to the steaming soup of dirt, bristles, feces, urine, blood, and grease in the wok. The idea of this feast is to eat a bit of everything from a hog when the kill is still warm and fresh. There will be blood-curd noodle soup, liver soup, tenderloin lettuce soup, tenderloin slices stir-fry, twice-cooked pork belly, and fat stir-fried with cane sugar, the very special treat for the butcher to go with the distilled sorghum baijiu. The relatives each go home with a chunk of pork; they will return a chunk, some days later, from their own hogs. The exchange of produce from one’s labor symbolizes and strengthens the bonding of kinship and friendship.

After the slaughter, people get busy right away, launching the busy La Yue schedule. It’s time to preserve the pork. The salting process varies regionally, but not much. The process lasts for around two weeks, and we make sausages in the meantime. On a rare sunny day, we take out the salted pork, with proper dehydration, for rinsing and air drying.

In rustic households, it’s still common to use firewood for cooking in firepits, emitting copious amounts of smoke, ideal for smoking the salted pork. You simply hang the chunks above the firepit, saving the trouble of a separate smoking process. If you are in the mood for larou, you take down a piece to clean off the soot. Some pork is smoked for over a year, turning putrid and moldy. The bad fat makes your throat furry. Like you ate an unpeeled kiwi. Few non-local people know how to appreciate this style of bacon. The oldest larou I had was a two-and-a-half-year pork knuckle, which no longer tasted like pork, so much as cured leather flavored by stinky tofu.

In late 2021, there were rumors online saying that it’s no longer legal to slaughter hogs at private households according to a new ordinance. If this was true, an important year-end feast was going to vanish. I asked Mom about it because she and her neighbors bought pork from local butchers, who used to slaughter hogs themselves.

“No wonder the meat prices went up and up,” Mom told me after making inquiries to her butcher, who happened to be my remote cousin in the same clan. “Starting from last year, the butchers are not allowed to slaughter hogs at their homes.”

The two butchers have been in business in my little town for decades. I used to see them herding hogs on the mountain trails, bought directly from the peasants. They’d slaughter them in the wee hours to make sure of a fresh kill. At the butcher’s stand, all my aunts and uncles are experts at judging the freshness of pork, by examining the colors. If the color is off, they’d have fish that day. Nobody buys pink pork. Even if they put scarlet pork in the freezers all the same.

“Do they source pork from abattoir companies, like the supermarkets downtown? That can’t be possible.”

“They are required to send the hogs to a designated abattoir in Jiasi, where they can get the paperwork for food safety.”

Jiasi is eight kilometers, two markets away.

“But can you slaughter pigs at home? Is it legal?”

“Of course, it’s legal. Your Uncle Ping slaughtered two pigs in August. We all went and bought a chunk. Your Aunt Mei bought half a pig. She has a big family.”

Even though it’s been years since Mom had a Year Hog to slaughter, I checked the updates of the ordinance, dubbed as “the toughest hog-slaughtering ordinance in history.” The latest version of the Hog-Slaughtering Regulations Ordinance was signed by the Premier in June 2021 and came into effect two months later. This was the fourth time they amended the ordinance since its implementation in 1997. And, to my relief, the very second item of the “General Provisions” states that the regulations make an exception of “slaughtering for private consumption in rural areas.”

The spectacle and the feast live on.

Rural work in Chongqing revolves around the pigs in the pen and the rice in the paddies. Mom still grows corn and sweet potatoes every year, even if she’s stopped raising hogs for years — she now feeds chicken and ducks with them. The amount of care to the livestock and fowls can be matched only by the fastidiousness of how we slaughter and consume them. Cured pork attains its special place in Sichuanese cuisine because the humid climate necessitates it.

Still, it doesn’t explain why all other animals must also be killed right in front of your eyes and cooked fresh. Here, frozen pork is detested, Hunanese style dried fish nonexistent, and frozen chicken drumsticks and chicken feet imported from Kentucky only fit to be braised in dark soy sauce or boiled and pickled with hot chili peppers.

Perhaps at this point, I should clarify one point. I’m from Chongqing, but I was born in Sichuan. It’s not easy to tell them apart if you are not talking about cartography. Right till 1997, Chongqing was a metropolis within Sichuan, so our dialects and cuisines share the same history. But if you have to tell them apart, the food is a good indicator. Or at least, Chongqing makes a lot of efforts to carve out a culinary identity of its own, especially the Hot Pot and the Jianghu Style.

Jianghu, or the rivers and lakes of the underworld society, the self-proclaimed regional character, pretty much says it all: plebeian, rustic, mixed, and above all, heavily and passionately flavored and spiced.

If you crave pickled green fish fillets, a grass carp would be ideal. Silver carp, with more treacherous small bones, is better eaten chopped. The fishmonger guts fish for free, either fillet or chops, for essentially, traditional Jianghu Style has only one way to handle fish — quick-boiling it in broths, differently flavored ever so slightly that only locals could tell. A minimal change of any element is considered innovation.

A trip to a farmer’s market in Sichuan is a journey to a bloodbath, as a British food writer described it. Fishes, mostly pond-raised, freshwater carps, swim in cramped tanks or large buckets, kept alive by air pumps. The fishmonger stuns the fish with a mace on the head, guts its white, fatty belly, and discards the black entrails, saving the milky white float. Fillet the flanks, and the head, tail, and vertebrae form the stock of the broth. Fish blood is not copious, but the smell is pungent. Before the popularization of the fridge, you were advised to rush home and cook it as soon as possible in case it turns rancid.

There is a growing debate in China about what animals we should and should not eat. Sometimes, the debate is elevated to a cultural war between traditions and what are believed to be imported values. Many of the younger generations keep cats and dogs as pets, not as rat catchers and house guards as my grandparents did. However, the sense of guilt in eating dogs, or any animal for that matter, is not entirely imported from the West. Not killing is the first of the ten precepts, or sīla, of Buddhism (originally from west of China, of course).

One summer, when my grandfather was still with us, my second uncle poisoned their mischievous dog who had attacked several passers-by. So we were having a feast of dog stew. When the stew of unrecognizable meat chops was simmering, my grandfather muttered that eating dogs will bring karmic retribution (as well as vengeful snakes). Yet, he was going to eat it all the same.

Grandfather had a special prayer, “I am upholding the sīla in my heart; whatever may pass through my throat, my heart is pure.” An invocation to Jigong, a legendary Twelfth-Century Buddhist monk, who broke the monastic codes of not consuming alcohol and meat while got to keep his supernatural powers. The mantra might have kept my grandfather’s mind at ease for a bit, but I doubt it would have cleared his conscience. My second uncle, who has polio, did not eat the stew.

Author Bio:

Qin Guibing teaches English at Shenzhen Technology University. He received his MFA in creative writing in 2015 and PhD in English in 2019. His primary interest is fiction, and he is working on several short stories and a novel.

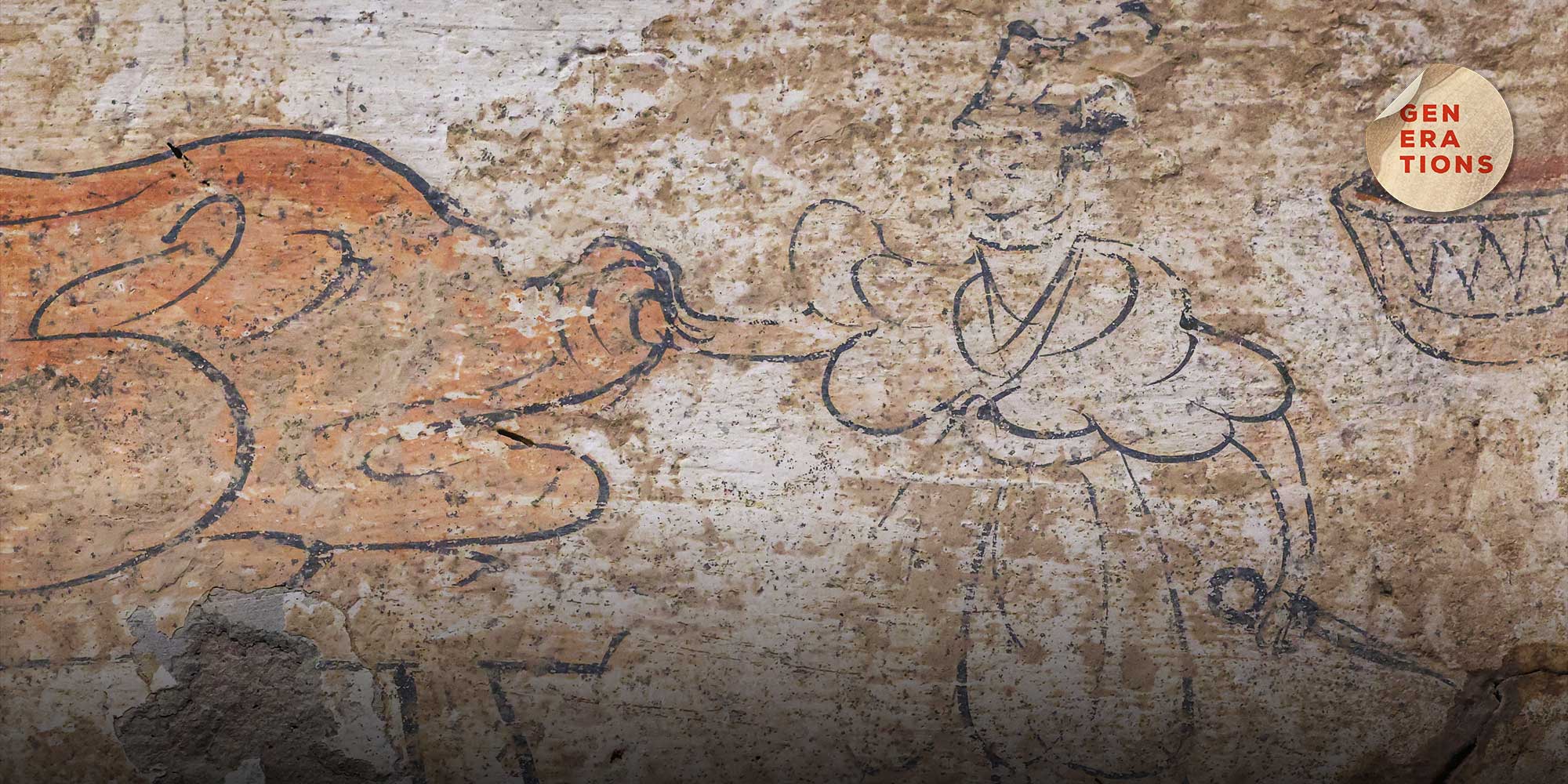

(Header image: A painting depicting the butchering of a pig from the Wei and Jin Dynasties period, excavated in Gansu Province. Yuan Huanhuan/VCG)