Tales of “Tiger Women” from Ancient China

In ancient China, Confucian traditions required women to be gentle and obedient. According to “The Book of Rites,” a collection of texts mainly published in the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) on the society and politics of the Zhou era (1046 – 256 BCE), unmarried women must obey their fathers, while married women were supposed to be subservient to their husbands and obey their sons if their husbands died. Wives who failed to meet the requirement would be called “female tigers,” generally a pejorative term for tough, imperious, or “unreasonable” women — similar to the modern term “tiger mom,” though not exclusive to parents.

Throughout history, many women gained — often unfair — reputations as intractable. Much of this stemmed from the sexism of patriarchal ancient Chinese society. A closer look reveals most of the women labeled “female tigers” merely stepped in when their husbands scuffled with others, or disliked them visiting prostitutes and taking concubines. Here are some of the most famous “tiger women” from ancient China:

The woman who frightened an assassin

Zhuan Zhu was one of the “Four Assassins” of ancient China, each of whom became famous for killing a tyrant. Born in the Spring and Autumn period (770 – 476 BCE), he was hired by Prince Guang of the State of Wu to assassinate the Wu king. Prince Guang arranged a dinner with the king and Zhuan disguised himself as a servant, hid a knife in the belly of a cooked fish, and stabbed the king to death as he served the fish to him. The king’s bodyguards killed Zhuan at the scene as he tried to make his escape.

But this supposedly fearless assassin was most afraid of his wife. According to The Spring and Autumn Annals of Wu and Yue, a historical record from the Eastern Han dynasty (25 – 220), when Wu Zixu, an official serving Prince Guang, met Zhuan for the first time, an enraged Zhuan was fighting ruffians on the street. But when Zhuan’s wife appeared, and asked him to stop fighting and return home, to everyone’s surprise, he immediately ended his combat and left with her.

Surprised, Wu asked Zhuan why he was so obedient to a woman, to which he replied: “I am second to just one person, but I am above all the others.” Hearing that, Wu concluded that Zhuan was brave, but not reckless, and so recommended him to Prince Guang for the assassination mission.

Though details of Zhuan’s wife are sparse, including even her surname, she was recorded as a “tigress” in official records, while Zhuan was labeled “the first henpecked man in history” by scholars in later dynasties.

The prime minister’s wife who refused the emperor

Fang Xuanling was prime minister under the reign of Emperor Taizong in the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), and his wife, surnamed Lu, had a reputation for being virtuous and loyal. According to The New Book of Tang, an official history finished in the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), when Fang fell severely sick and thought he would soon die, he told Lu: “I am dying, but you are still young. Do not live in widowhood. Find another person, and have a good life with him.” However, Lu refused and even poked one of her own eyes out as a symbol of her loyalty to Fang and vowed she would never marry again.

Yet in numerous folk tales, Lu is described as a stubborn and shrewish woman; her obstinacy even birthed the phrase chicu, or eat vinegar, which means to be jealous of a love rival and is still in use today.

According to The Anecdotes of the Emperors, Ministers, and Common Men, a novel by writer Zhang Zhuo recording anecdotes in the Tang dynasty, Fang was so afraid of Lu that he didn’t take any concubines, a scandal in those ultra-patriarchal times.

Upon hearing of Lu’s influence, the Taizong Emperor decided to interfere and awarded Fang a concubine. Despite the emperor’s order, Lu forbade the concubine from joining their family. The emperor was enraged by Lu’s disobedience and summoned her to court, telling her to drink a cup of deadly poison or accept the concubine. Lu drank the liquid without hesitation.

But she didn’t die. The emperor laughed. He told Lu the cup contained only vinegar —it had been a test of her nerve. The emperor was so impressed by Lu’s principled nature that he revoked the award of Fang’s concubine and never interfered in their marriage again.

The “Hedong Lion”

The wife of Chen Zao was considered so fierce by contemporaries that Song dynasty poet Su Shi, also known as Su Dongpo, labeled her the “Hedong Lion.” In one of Su’s poems, he described his friend Chen’s fear of his wife: “My friend Chen Zao is so poor. When chatting with friends at a party one night, he suddenly heard a Hedong lion’s roar. Scared so badly, he could only stand there helplessly leaning on his walking stick.”

Chen was a talented scholar, who also enjoyed drinking, partying, and soliciting prostitutes. Chen’s wife, surnamed Liu, was from Hedong, in the southwestern part of today’s Shanxi province. Liu was apparently short-tempered and frequently broke up Chen’s parties by yelling at him and expelling his friends. Su used “Hedong lion’s roar” as a metaphor for Liu’s shouts.

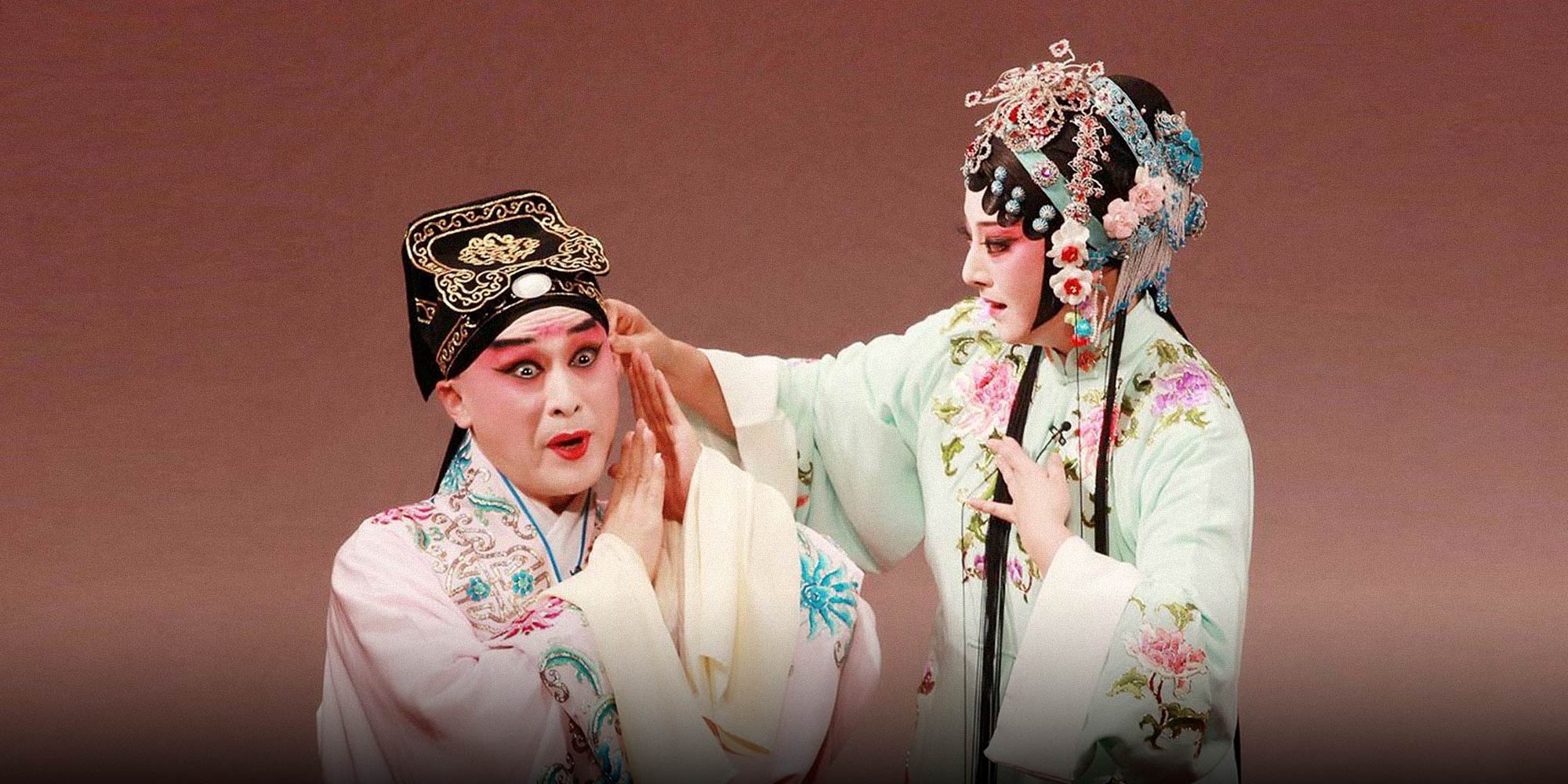

Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) playwright Wang Tingne based his play, The Lioness’s Roar, on Liu and Chen. In Wang’s play, after Liu found Chen having a party with friends and prostitutes, she brought Chen home immediately and forced him to kneel down by a pond in their yard as punishment. Su went to their home to defend Chen, but Liu kicked him out.

The story has been widely spread even today and has been adapted into countless plays, TV dramas, and movies. People often use the idiom “the Hedong lion roars” to describe a short-tempered wife quarreling with her husband.

Reporter: Sun Jiahui.

This is an original article from The World of Chinese, and has been republished with permission. The article can be found on The World of Chinese’s website here.

(Header image: A stage photo of a Kunqu opera adaption of “The Lioness’ Roar,” 2016. From @北方昆曲剧院 on WeChat)