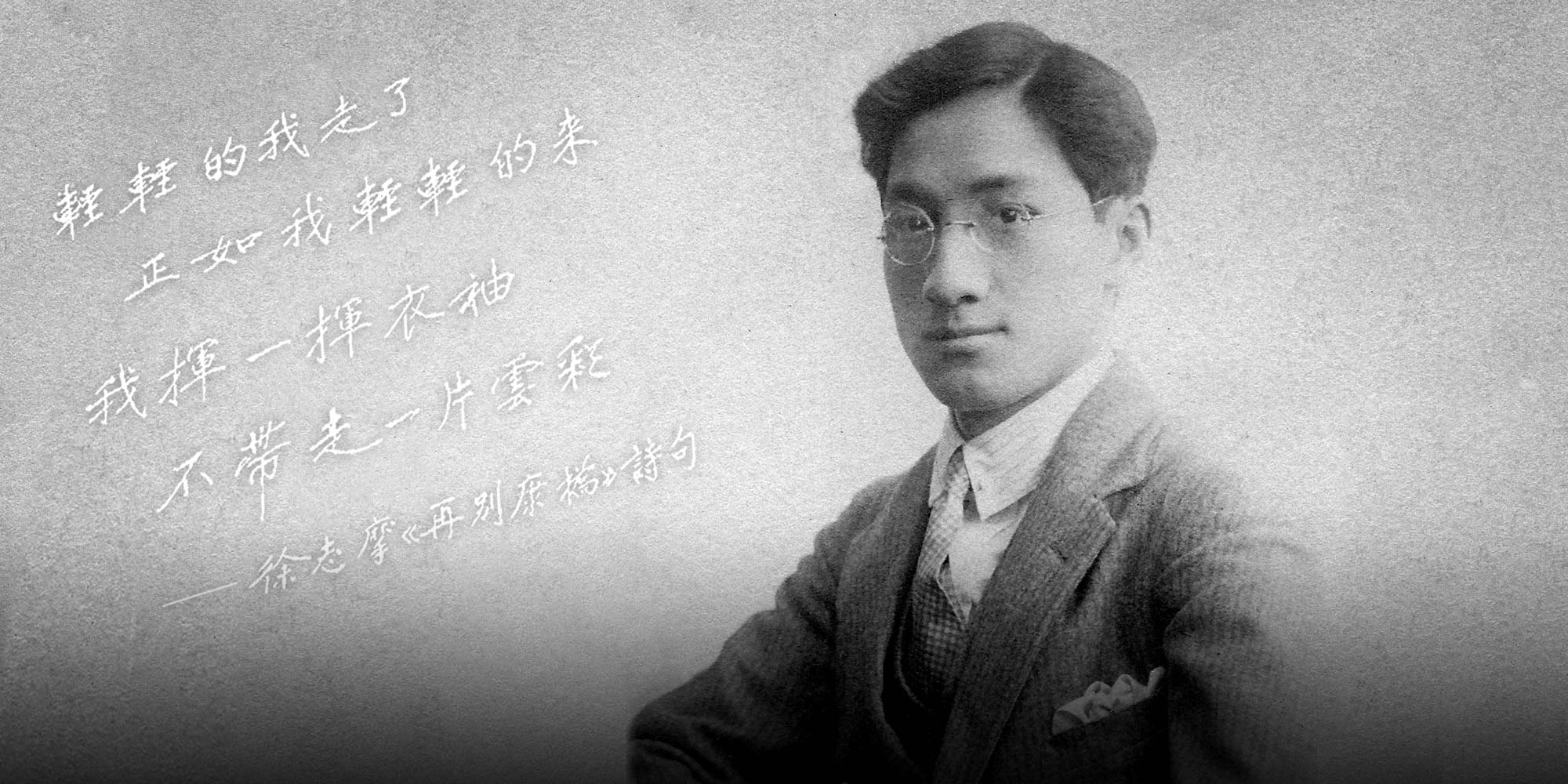

Remembering Modern China’s Greatest Poet

Editor’s note: In 2018, the Xu Zhimo Memorial Garden opened at King’s College, Cambridge. The garden commemorates one of the most celebrated Chinese poets of the 20th century, whose time studying in Cambridge in the 1920s not only introduced him to English Romantic poetry but also led him to write “Second Farewell to Cambridge,” one of the country’s most enduring modern poems. The following is an excerpt from a memorial piece by Xu’s biographer Chen Congzhou, translated for the first time for a new book by architect Yue Zhengyang, who participated in the garden’s design.

In the Spring of 1981, I took a southbound train back home after attending meetings in Zibo in Shandong province. As the train passed a station in Jinan, I was shocked by the station name “Dang Jiazhuang.” Fifty years ago, the poet Xu Zhimo died in a plane crash at Mount Kai near the Dang Jiazhuang station. Overcome with emotion, I carefully examined the slopes of the mountain. While I gazed out, the train kept moving forward with an unceasing clatter of wheels catching the railroad. For a moment, the sound of the wheels seemed more like the sound of passing time. As Mount Kai gradually disappeared from sight, I recited three short poems I composed in memory of the poet on the 50th anniversary of his death.

In August 1949, I edited and published the “Chronology of Xu Zhimo,” a comprehensive biography of Xu’s life. Due to length restrictions, several events — including events that occurred after his death — were not included in that book. Those missing events will be addressed in this article.

In trying to illustrate Xu’s life, I must first explain his familial relationships. Xu’s father, Xu Shenru, is the uncle of my wife Jiang Ding, as well as the uncle of my sister-in-law Xu Huijun. As I was raised by my sister-in-law, I am connected to Xu by multiple relatives. Shenru lived for 73 years, outliving his son by 13 years. Shenru was an open-minded national capitalist. In his hometown of Xiashi — a township of Haining County in Zhejiang province — he ran traditional business enterprises such as the Xu Yufeng Sauce Garden, Yutong Bank, and Renhe Silk Village, among others. Significantly, he founded a silkworm factory, a cloth factory, the Xiashi Electric Lamp Factory, the Shuangshan Workshop, and more. He was also active in both Shanghai and Zhejiang province’s financial industry; for a long time, he was the head of Xiashi’s Chamber of Commerce.

At that time, Xiashi was a prosperous business center of rice and silk, and Shenru knew that public transportation had to be developed first in order to promote local business. Initially, the Shanghai-Hangzhou Railway — founded by shareholders including Shenru — would make a stop at Jiaxing before heading directly to Hangzhou. Shenru, however, proposed the railway bend east and make a stop at Xiashi. A few local conservative parties firmly opposed Shenru’s railway plan — to the point of conspiring against him and destroying his house. Luckily, the railway was built based on Shenru’s vision. Nowadays, Xiashi is a district of Haining, an important city along the Shanghai-Hangzhou Railway. Both booming business and industry sectors rely heavily on this railway.

As the eldest grandson and only son in his family, Xu was doted upon by his grandmother and mother. As Xu’s father, Shenru took his son’s education seriously. Xu was sent to Hangzhou for middle school, where he received a modern education. After graduation, he pursued his studies in Beijing, before going abroad for further studies. Xu’s educational background was considered modern and progressive for his time.

As a young student, Xu was an enthusiastic writer, composing unrestrainedly. When he was a teenager, Xu’s essays were impeccable imitations of Liang Qichao — a well-known intellectual at the time. This explains why Xu later became Liang’s disciple. While studying at Xiashi Kaizhi primary school, Xu wrote a short essay titled “On the Defeat of Ge Shanguan at Tongguan.” (Editor’s note: Ge was a famous military general during the Tang dynasty.)

However, not only could he write elegant essays in classical Chinese, but his calligraphy was also beautiful and vigorous. It is hard to believe that a 14-year-old student could master calligraphy to such an extent. Xu developed his calligraphy style by imitating Zheng Menglong from the Northern dynasties. Xu’s extraordinary talent in calligraphy was rare among modern literature writers.

While attending the Prefectural Middle School in Hangzhou, he published progressive essays, including “On the Relationship Between Fiction and Society” and “History of Radium Ingot and the Earth.”

I obtained Xu’s most important essay from his cousin, Xu Chongqing. During his studies abroad in the summer of 1918, Xu wrote “Xu Zhimo on His Way to the United States.” The essay was printed in large typography on white paper and formatted as folded scripture. The impassioned composition of “On His Way to the United States” thoroughly reflected Xu’s patriotic concern for his country and people:

Ashamed of the decaying morals and collapsed nation —

It’s useless to speak of working hard for a mere moment.

Mourning the sudden demise of the country —

Those aspiring to serve the country rise up once,

determined to regain the lost land and vowing to serve the country.

When will it be the time?

When will it be the time?

It is time that we extend the fate of our nation.

It is time to fight back and keep the entirety of our homeland.

Youths, it is us who shall take responsibility and act immediately.

After Xu arrived in the United States, he wrote his self-imposed schedule in his diary:

[My four Chinese roommates and] I made rules that we would get up at 6 a.m., morning session at 7 a.m., to stimulate our sense of national shame, sing the national anthem every night, and go to bed at 10:30 p.m. During the day — besides studying hard and going out — we would exercise, run, and read the news.

When World War I ended, he wrote again in his diary:

Here comes the time when the sky cheers up and clouds change color. We celebrate and console each other with our pure, brave, and lasting patriotism. Ah! The empire is declining and the nation has lost its territory. The blood of the soldiers shall not be wasted for naught.

Xu’s words reflected the pure thoughts of a patriotic student studying abroad at that time. He respected Liang Qichao, and mentioned him often in his diary:

Liang’s “Three Founding Fathers of Italy” inspired me to be strong and courageous… Liang’s compositions move gracefully like a magical dragon whirling in the air. So powerful that they could tear down mountains. So unparalleled that they shadow the whole universe.

Liang’s essays made a great impact on Xu in his youth. I discovered Xu’s early diaries in 1947 while visiting the Xu’s family home (built after Xu’s death at Fan Yuan on Avenue Hague [now Huashan Road] in Shanghai; before, the Xu family lived in a house belonging to the Zhang family) and speaking to Zhang Youyi, Xu’s ex-wife who later became Xu Shenru’s adopted daughter. During my visit, she pulled out a signed autograph and two rice-paper notebooks of calligraphy titled “Zhimo’s Essays” and “Zhimo’s Diary.” On the notebook cover — beneath the title “Zhimo’s Essays” — Xu wrote “Honest Words.” Zhang told me, “Take these! You are attached to him emotionally.”

The notebook contained letters, essays written by Liang Qichao, and Xu’s diaries. Some essays were reading notes for the “Chu Ci” (“The Elegies of the South”) and “Shuo Wen” (“Origin of Chinese Characters”). He wrote pianwen (rhythmical prose characterized by parallelism and ornateness) very well; regretfully, no pieces exist anymore. His notebooks showed that he studied pianwen extensively. I edited two complete prose pieces out of the notes and published them in Shanghai’s newspapers and “Chronology.” The original notebooks are lost; only some blank papers are left. I felt deeply morose upon seeing the remnants.

Xu treasured his friends more than himself. After his death, someone referred to him as “everyone’s friend.” He was passionate and sincere with family and relatives. He had a broad network of friends — partly due to his upbringing as his father was socially active and well-connected to various contacts. The other reason was due to his character. From my casual survey, his friends included “scholars, farmers, workers, and businessmen.” Some of the friends were considered “rich,” while others were “poor.”

Xu’s extensive network contributed to his creative work. He wrote poems in Xiashi’s local dialect and included vocabulary only in use in the Xiashi countryside. While he lived in Three Aged Temple at Xiashi’s Eastern Hill, he often smoked and chatted with beggars and bought them food.

Xu subscribed to both old customs and traditions, as well as iconoclastic Western beliefs. Even though Xu and his father Shenru had great differences of opinion on the issue of his marriage, Xu still deeply respected his father. He despised being seen as the rich and young master from a traditional Chinese family, and instead carried his own suitcase and traveled widely in order to stand on his own two feet as an impoverished teacher. He was always short of money but refused to seek assistance from his father or family.

His financial setbacks eventually cost him his life due to his tendency to fly on dangerous airlines that were free of cost. When Shenru learned of his son’s death, he mournfully sighed, “Nothing left!” Shenru’s two words expressed the complicated relationship between father and son. Afterward, the Xu family business was handed to Zhang Youyi; her son Jikai — Shenru’s only grandson — became the hope of the Xu family.

This article, translated by Yue Zhengyang, is an excerpt from the book “The Xu Zhimo Garden in King’s College, Cambridge” published by the Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House. It has been lightly edited for length and clarity and is republished here with permission.

(Header image: Visual elements from Yue Zhengyang, reedited by Sixth Tone)