As Dalian Saves Its Seals, Sea Cucumber Farmers Feel the Cost

The sea cucumber farms in Wafangdian, a county-level city on the outskirts of Dalian, in the northeastern Liaoning province, are easy to spot.

They comprise massive, rectangular lots neatly arranged along the coastline that adjoins Xianyuwan Town and Santai Township. Each lot has a surface area of about 33,000 square meters and yields a catch of about 7,500 kilograms.

Such is the city’s reputation that, in 2020, the China Fisheries Association awarded it a title: “Home of the Liaoning Cucumbers.”

But for several years now, Wafangdian’s aquaculturists have been caught in a tug of war with authorities over land use. The sea cucumber farms are located right within the core zone of the Dalian Spotted Seal National Nature Reserve — the only national-level reserve for the species in China.

On Sep. 3, 2021, in the most recent escalation of the dispute, the Wafangdian municipal government issued a notice that required farmers in Xianyuwan Town and Santai Township to cease production, dismantle their facilities, and completely evacuate the area before Oct. 31, 2021.

The sea cucumber farmers interpreted this as a non-negotiable, all-encompassing ban.

But their problems began decades earlier. In 1992, Dalian established a municipal-level nature reserve for the spotted seal, which was upgraded to the national level in 1997. No one is allowed to enter the reserve, and no production facilities can be constructed in the core zone.

Sea cucumber farmers believe otherwise. “But our coastline is just alkali soil, reed ponds, and barren beaches — spotted seals won’t come here,” says Jia Dezhi, an aquaculturist in Santai Township. Echoing Jia’s sentiment, many farmers never left the core zone.

On Jan. 1, they submitted a petition to the mayor of Wafangdian, dissenting against the borders of the core zone, and requested readjustments.

Since its establishment, the reserve’s borders have already been reduced twice, but sea cucumber farmers say their core concerns have yet to be addressed.

Zero-day vulnerability

In 2021, the spotted seal was declared a national first-class protected animal. It measures about 1.2 to 2 meters long and is the only pinniped marine mammal capable of breeding in China’s waters.

Among the only eight zones in the wild across the world where this species breeds, the southernmost is the icy northern reaches of Liaodong Bay in Liaoning.

Every October, spotted seals migrate north to the bay. And from January to February the following year, females give birth on the bay’s ice floes. After the coastal ice and snow melt in March, they split up and scavenge the nearby waters and shores for food.

Over time, the mouth of the Liao River has become one of their main habitats, where they climb the river’s muddy banks to rest and molt. The spotted seals often stay until May, and then leave the Bohai Sea and migrate to Baengnyeong Island in South Korea in the summer.

The seals only climb onto floes or shores to reproduce, nurse, molt, or rest. Highly alert creatures, they dive back into the water at the slightest sign of danger. It’s why hardly anyone has ever seen spotted seals in Liaodong Bay other than local fishermen, who refer to them as “sea dogs.”

Since their fur, blubber, and male genitalia are all highly coveted, the spotted seal has been targeted across Liaodong Bay since the 1960s.

Wang Pilie was one of the first scientists to study spotted seals in China. Up until his death in 2021, he researched marine mammals for more than 50 years. According to his statistics, the number of spotted seals in China plummeted from a peak of about 8,137 in 1940 to only about 1,908 in 1979. In the early 1990s, he began calling for a nature reserve.

A series of investigations Wang conducted showed that the northern reaches of Liaodong Bay were key breeding grounds for spotted seals, while they were hunted in the south of the bay.

Zhang Wei, a researcher at the Dalian National Nature Reserve Administration (DNNRA), participated in the demarcation of the reserve zone in 1992. He recalls that one dominant assumption was that the northern part of Liaodong Bay was naturally protected from poachers from mid-December to late March the following year. “It all becomes ice — people can’t reach it,” he says.

Therefore, the reserve was established in the southern part of the bay, covering 909,000 hectares that included the then sparsely populated coastline and waters west of Dalian, as well as more than 70 islands. It comprised a core zone, a buffer zone, and an experimental zone.

That was when Jia Dezhi and his fellow aquaculturists found themselves in the middle of the core zone.

Han Jiabo is a former director of the Liaoning Marine and Fisheries Research Institute, where he is now a researcher. The institute is best known for studying the spotted seals. He underscored that the core zone should be the seals’ breeding area in the north. It means that the planning of the reserve was questionable from the start.

Escalating conflicts

As of Dec. 27, 2021, the borders of the spotted seal reserve not only encompassed coastal waters but also mountains, cemeteries, a road five kilometers from the beach, as well as a tide embankment built in the 1980s.

It left locals perplexed. “Why would the seals come to the cemetery? How would they end up on the road?” asks Qiao Hongquan, an aquaculturist in Xianyuwan Town.

According to Han, in the original demarcation system, the boundaries may have been established on the shoreline, but in the new system, the same boundaries may now be located further inland.

It is also possible that, over the last few years, the coastline has been altered after land reclamation — boundaries that were originally on the shore are now situated on dry land.

According to the local government, illegal land reclamation in the region has been rampant. An announcement by the Wafangdian Municipal Government stated that a residential community built in 2013 was located in the core zone.

The construction of this community, it said, “was the result of external factors, i.e., the state’s inaccurate delineation of the reserve; as well as internal factors, i.e., the illegal issuance of reclamation certificates by the Wafangdian Ocean and Fisheries Bureau. Of these two factors, the latter played a leading role.”

Wafangdian’s aquaculturists, however, face a different dilemma. Their sea area use licenses expired in 2016, and all renewals have since been rejected.

But Jia Dezhi insists that, at the time, authorities did not tell them why the licenses could not be renewed. “They didn’t say that it was because we were located in the reserve — but they did say that we could continue to produce, and they’ve never come to check since,” he says.

“They also said that if we eventually succeeded in renewing our licenses, we could pay retroactively for the years when we operated with expired licenses.”

Zhang Yue, chief of the Sea and Island Section of the Wafangdian Natural Resources Bureau, says their licenses have not been renewed to comply with the management regulations of the reserve — something the farmers were, he says, adequately informed about.

Asked why the aquaculturists still operated without penalty even after, Zhang said he didn’t know.

According to Zhang, in July 2020, the Wafangdian Natural Resources Bureau issued a notice ordering all aquaculturists to cease activities, but were unable to reach any of them. “We serviced it to every aquatic farm, but not one of the farmers signed for it,” he says.

But several aquaculturists say they neither received nor saw the notice posted anywhere.

The September ban was issued after separate central government teams conducted two inspections in 2021. That’s when the farmers grasped the gravity of the situation.

On Oct. 25, aquaculturists in Xianyuwan Town and Santai Township filed an “administrative reconsideration” to the Dalian Municipal Government, under whose jurisdiction Wafangdian city falls. This application was rejected on Dec. 20. Several have since said they would soon file administrative lawsuits.

Meanwhile, the Wafangdian Municipal Government has reiterated its determination to enforce the law. According to a memo shown by Zhang Yue, on Dec. 29, Wang Zhanlin, the vice mayor of Wafangdian City, requested a joint operation between departments.

The measures included cutting off the aquaculturists’ power, and if necessary, with assistance from local police and tactical units.

Boundary changes

Historically, the boundaries of the reserve have been redefined twice — in 2007 and 2016. With the first adjustment, the reserve was reduced to 672,000 hectares, which shrunk to 562,000 hectares after the second. And while in 1992 it comprised one core zone, now the reserve has two separate, smaller cores — one each to the north and south.

In 2005, Liaoning declared the harbor of Dalian’s Changxing Island an industrial zone. It’s also why the reserve was redefined two years later: to exclude the western and southern parts of Changxing Island and their surrounding waters.

An insider involved in the initiative says that, at the time, experts staunchly disagreed with a proposal to also exclude the northern part of Changxing Island from the reserve, where spotted seals were known to climb ashore. “Excluding the north would mean the functionality of the reserve was compromised,” said the insider.

In 2010, the industrial zone was upgraded to a “national economic and technological development zone.” At present, the island hosts the world’s largest production base for purified terephthalic acid (PTA) — a crucial raw material in various products, including polyester.

The areas excluded from the reserve during the two adjustments have also been used for several development projects, including a nuclear power station and an international airport. Some commercial and industrial shipping channels, which were once part of the reserve, have been excluded too.

DNNRA Director Shi Xiaoming says that the administration’s daily tasks include ecological monitoring, with the water being tested in the reserve once every season, and held to the highest water quality standards.

The administration has also submitted a plan for a third redrawing of the reserve, which the Ministry of Natural Resources and the National Forestry and Grassland Administration has approved to solve the longstanding problems caused by the delineation of its boundaries.

The plan is currently awaiting approval from the State Council.

Han Jiabo believes the reserve as it is defined now still maintains a healthy balance between economic development and environmental conservation.

Counting the cost

Despite being a national first-class protected animal, the population of spotted seals has not been surveyed for more than a decade — an oversight that has drawn criticism.

In a research paper, Han said that the most effective method to survey the population was aerial observation. However, with funding constraints, among other factors, few have been sanctioned.

Zhang Wei says the DNNRA once discussed using icebreakers with Han’s institute. Such a ship costs 13,000 yuan ($2,000) per hour, and every operation requires four such vessels out at sea for more than 10 hours each day.

Moreover, each expedition also requires drones and helicopters. Given that a survey takes several days to complete and needs to be repeated the following year for confirmation, the cost of such an initiative Zhang estimates “would require anywhere from 3 to 5 million yuan.”

The last time Han’s institute investigated the population of spotted seals was in 2006 and 2007, when they conducted an aerial survey of the seals’ breeding grounds on the ice floes of Liaodong Bay. In 2006, they counted about 1,200, while in 2007 it was about 890.

In 2020, the China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation (CBCGDF) claimed that the Ministry of Agriculture “described” this very data as “the results of the surveys in 2006 and 2007 showed the population to be around 2,000” — a statement parroted across the media.

In the same year, the CBCGDF simultaneously monitored spotted seal populations across the country. Ultimately, only 338 seals were spotted, and the foundation estimates that the total population was no greater than 500.

Poaching, however, has gradually decreased across the reserve. In February 2019, acting on information, the Changxing Island police seized 100 spotted seal cubs at a breeding facility in Wafangdian, of which 62 survived.

The suspects confessed that, beginning in mid-to-late January 2019, they had made several trips to hunt spotted seal pups in the icy waters in the north of Liaodong Bay.

Court verdicts in several poaching cases in recent years show that almost all defendants confessed that they had chosen to hunt seals in the northern reaches of Liaodong Bay because they knew that this area was their breeding ground and not part of the reserve.

“Our routine patrols couldn’t get there,” says Shi Xiaoming, director of the DNNRA. He asserts that one of the reserve’s biggest problems currently is that it doesn’t include the seals’ main breeding area.

At present, the DNNRA only conducts manned patrols where poachers are likely to hunt, which is inefficient. Shi Xiaoming says that relevant divisions are petitioning authorities to establish monitoring systems at 36 key ports and terminals throughout the reserve.

In Dec. 2021, the Taskforce for the Protection and Management of Spotted Seals in Dalian formulated a plan for the current migratory period. From Jan. 1 to April 30, 2022, all relevant authorities across district and municipal governments will be required to cooperate.

One of the key points of this plan is “grid management” — arranging spotters along the shore in every village. Once a sighting of suspicious activity is confirmed, it will be sent up the chain of command.

As locals, aquaculturists, and authorities inside and outside the reserve still debate its borders, the spotted seals last month began their migration to the northern part of Liaodong Bay. There, they will breed and rest on the ice, far away from land, ships, and people.

This article was originally published by China Newsweek. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and published with permission.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Zhi Yu and Apurva.

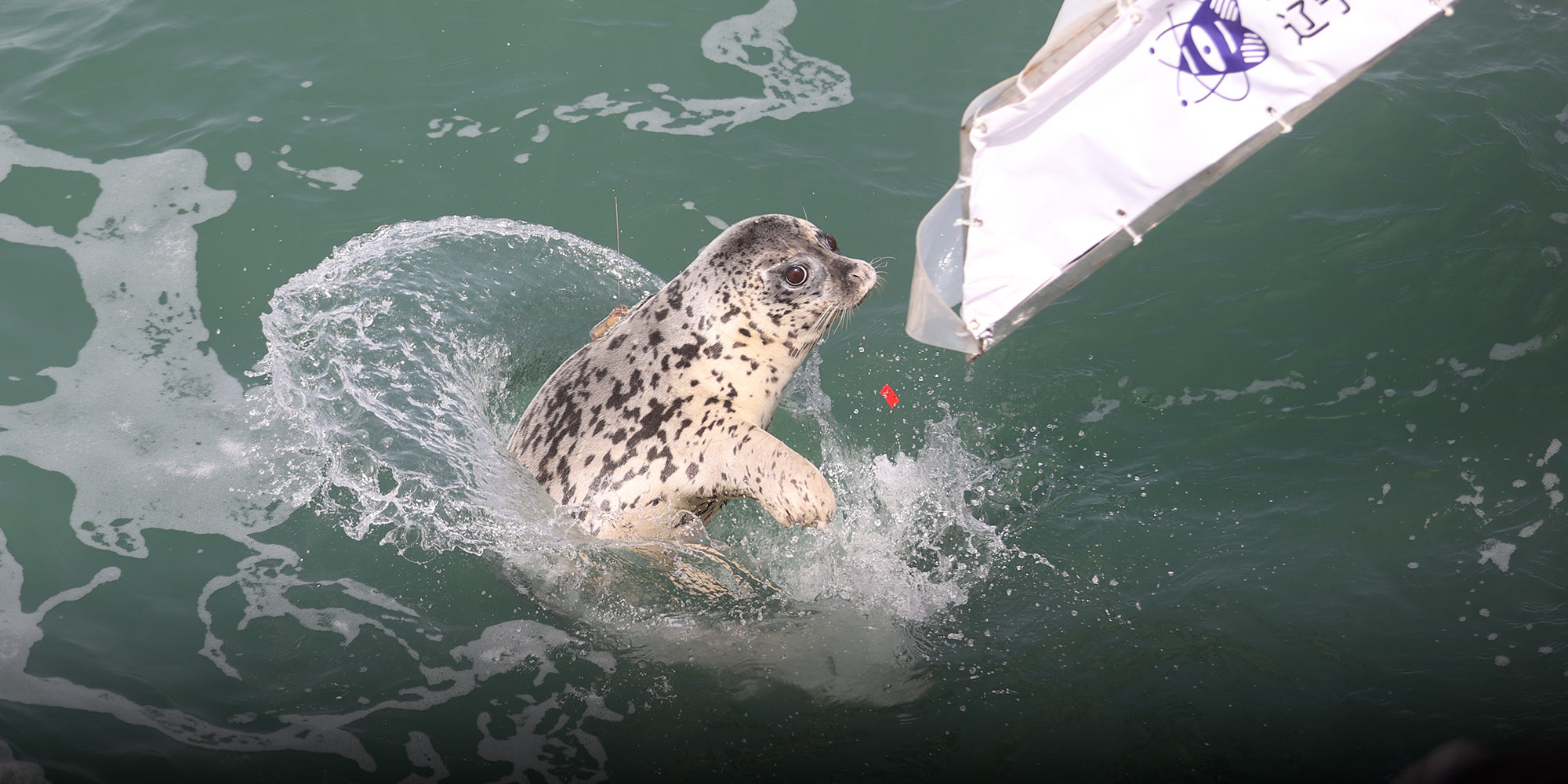

(Header image: A spotted seal being released into the wild in Dalian, Liaoning province, April 2021. People Visual)