Chinese Archaeology: Past, Present, and Future

On the morning of December 14, China’s State Administration of Cultural Heritage made a stunning announcement: Chinese archaeologists had identified the “Great Tomb of Jiangcun,” near modern-day Xi’an in the northwestern Shaanxi Province, as the resting place of Emperor Wen of the Han Dynasty (202 B.C. - A.D. 220) — one of the most renowned and popular ancient Chinese monarchs.

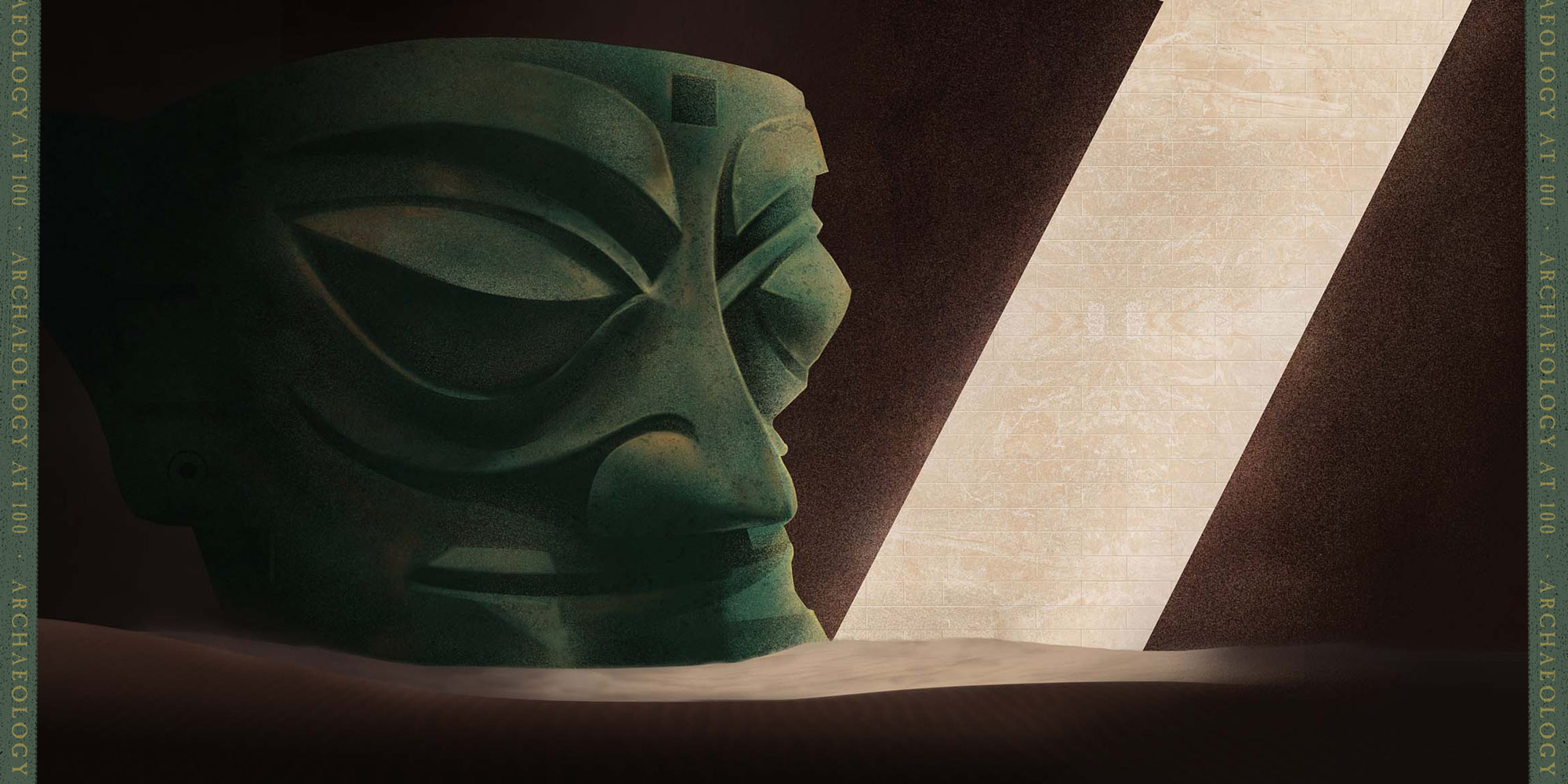

The news capped a banner 12 months for Chinese archaeology. In March, archaeologists uncovered over 500 relics from the mysterious Sanxingdui culture in what is now the southwestern Sichuan province. In September, a team led by David Dian Zhang published a paper detailing an even more remarkable find from the Tibetan Plateau: the world’s oldest immobile artwork, 140,000 years older than France’s Chauvet cave paintings.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of Johan Gunnar Andersson’s 1921 excavation of the Neolithic Yangshao site, widely recognized as the starting point of Chinese archaeology. That makes the field a relative upstart, especially compared to China’s rich traditions of historiography and epigraphy, but it hasn’t kept archaeology from becoming one of the country’s most important academic fields over the past century.

Much of archaeology’s initial appeal was as a subfield of history. Almost immediately after Andersson’s expedition, Chinese scholars recognized the potential power of archaeology to settle simmering disputes about the country’s prehistory. Western-oriented groups like the “Doubting Antiquity School” emerged around this time to question the existence of dynasties and events long taken for granted; and both sides of the ensuing debates saw archaeology as a valuable “tool” for making their arguments.

Andersson’s work also played a role in this dynamic, as his theory that the Yangshao culture had its origins not within China, but in Central and Western Asia, stimulated widespread interest in archaeology. These unexpected and often unwelcome ideas disquieted many Chinese scholars, but also reinforced their belief in archaeology’s power to make — or break — a nation’s self-image.

To write history is to shape, to cull; it is a process of invention, however well supported. At least in theory, archaeology is different: It is concerned with that which physically exists. That notion has been reinforced in China by recent technological advances and approaches that privilege high-tech tools, sometimes at the expense of old-fashioned hypothesis testing.

But archaeology is also a discourse. For evidence, look no further than the political importance placed on archaeology to confirm, expand, and tell the glorious history of China. The discipline’s rise over the past 100 years mirrors that of the Chinese nation, but it has also been characterized by a certain reactiveness — a vision of archaeology as a tool rather than a discipline. If this year’s discoveries are any indication, the future is bright. Yet archaeology can be so much more than just a way to answer the questions of history: If the second hundred years of Chinese archaeology are to be as successful as the first, Chinese archaeologists must ask their own questions — and find their own answers.

In the following three articles, three Chinese archaeologists engage with and discuss the past, present, and future of Chinese archaeology.

Series translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell; copyeditor: Johanna Costigan; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao; visuals: Fu Xiaofan and Ding Yining.

(Header image: Visual elements from Shijue Select/People Visual, reedited by Sixth Tone)