Inside the Subway Disaster That Killed 14 in Central China

HENAN, Central China — At around 4 p.m. on July 20, Zou Deqiang and his colleague Wang Yunlong were struggling to call a cab. It had been raining heavily all day in Zhengzhou — a sprawling megacity in central China — and few vehicles were on the inundated streets.

The pair, who were in Zhengzhou on a business trip, weren’t overly concerned: Minor flooding incidents happen regularly in the city. They jokingly snapped a video of themselves dipping their feet in the ankle-deep water, and headed for the subway.

It would be the last time Zou ever saw daylight.

Just two hours later, the two men found themselves trapped underground inside a packed subway train amid a devastating flash flood. With help slow to arrive, the passengers became increasingly desperate as the carriages rapidly filled with water. Fourteen people would eventually die in the tunnel — including Zou.

The disaster was just one of many that struck Zhengzhou that day, as surging floodwater left nearly 300 dead across the city. But it was a preventable tragedy.

Over the past two weeks, Sixth Tone has spoken with eyewitnesses, experts, and survivors to reconstruct a timeline of events leading up to the disaster. Our reporting suggests that had swifter action been taken, a fatal accident may have been averted.

By the afternoon of July 20, it was already clear to Zhengzhou’s weather bureau that the rainfall battering the city was no ordinary downpour.

Between 8 p.m. on July 17 and 8 p.m. on July 20, the city received just under 620 millimeters of rain — nearly an entire year’s worth of rainfall. The bureau issued five storm red alerts — its highest-level alert — in the 24 hours before the disaster in an attempt to raise the alarm.

A red alert should trigger a citywide shutdown of all unnecessary outdoor activities, with students and commuters encouraged to stay at home. But the warnings failed to catch the city’s attention.

From 4 p.m., the rain became even stronger — a record-breaking 200 millimeters of precipitation falling in just one hour. Streets rapidly turned into rivers, and water began pouring into underground parking lots and tunnels.

Yet when Wang and Zou boarded the subway, the city’s metro system was still running an almost normal service. Zhengzhou Metro Group, the network operator, had begun closing some station entrances at 3:40 p.m. to prevent water from flowing onto the platforms. But it did not order a full service suspension until 6:10 p.m.

Wang and Zou ducked into Huanghe Road station and got on a Line 5 train headed west. Line 5 is a busy commuter route that runs in a loop around the city center. That day, there were more than 500 passengers on the train, with many choosing to take the subway as the roads were flooded.

The passengers had no idea at this point that they were in danger. But their train was heading directly toward the most compromised section of the tunnel.

At the northwestern edge of Line 5, there is a rail yard called Wulongkou, from which Line 5 trains enter and exit the main tracks. As the rain became fiercer through the afternoon, the rail yard’s flood defenses began to buckle, sending water cascading down the tunnel toward the nearest station: Shakoulu.

In a statement issued after the disaster, Zhengzhou Metro Group said the rail yard’s flood defenses were destroyed at 6 p.m., leading the firm to shut down the entire network 10 minutes later. But eyewitness accounts suggest damage was apparent much earlier.

By around 5 p.m., floodwater had already breached the wall protecting the tracks inside the rail yard, an eyewitness — who requested anonymity for privacy reasons — told Sixth Tone. A photo taken by the person, time-stamped 5:02 p.m., shows that several parts of the wall had collapsed and disappeared under the water.

Wang Xiaodong, a construction worker who was resting in a porta cabin near the entrance to Wulongkou that afternoon, told Sixth Tone that water began flowing into his cabin at around the same time, forcing him to take shelter on top of a bunk bed. A photo Wang took from inside the room at 5 p.m. shows a man standing ankle-deep in water, with a washbasin floating nearby.

By 5:30 p.m., the flood had also destroyed a brick wall just outside the rail yard’s pumping station, leaving a gap several meters wide, two other construction workers who were near the site at the time told Sixth Tone.

Yet, unaware of the peril that lay ahead, the Line 5 train continued speeding west. At around 5:40 p.m., it stopped at Haitansi station, then restarted and headed toward Shakoulu, the closest station to the rail yard. This was when the passengers’ nightmare began.

Before reaching Shakoulu station, the train came to an abrupt halt, unable to continue due to the torrents of water already pouring into the tunnel. The train was stuck on a steep stretch of track designed to help trains decelerate as they approach the platform.

Video footage circulating online showed subway passengers trapped in a flooded carriage of a Line 5 train in Zhengzhou, Henan province, on Tuesday. Rescue efforts are underway, according to local media. pic.twitter.com/POdT5aBn8a

— Sixth Tone (@SixthTone) July 20, 2021

Floodwater started flowing into the carriages around 6 p.m., according to several survivors. Within minutes, the water was already several inches deep in the rear carriage — where Wang and Zou were located. Zou recorded a video of the partially flooded subway car and sent it to his wife.

As the train rapidly filled with water, passengers sent out desperate pleas for help to family members, emergency services, and via social media. Yet many of them would remain trapped inside the carriages for over three hours, watching the water rise ever higher and struggling to breathe as they gradually ran out of oxygen.

With no signs of immediate rescue, people on the train tried to take matters into their own hands. Staff members managed to open the doors inside the front carriage, allowing those on board to access an emergency walkway running along the tunnel toward the station.

Unlike cities like Shanghai and Beijing, the Zhengzhou subway system has yet to install designated emergency exit doors on its trains, which could have facilitated an evacuation.

About three dozen people managed to escape along the emergency walkway to safety. But before more could join them, the torrent became more violent. Cascading water dislodged the train from the track, blocking the escape route and forcing the remaining passengers back into the carriage, Wang told Sixth Tone.

“We were all panicked and wanted to ask the head conductor what we should do next,” one survivor told domestic media. “We felt like there was nowhere to ask for help.”

Inside the train, the passengers’ panic grew. The power supply went down, plunging the carriages into darkness, survivors recalled. Passengers held each other’s hands and exchanged comforting words, while others phoned loved ones to say their goodbyes.

As the water continued to rise, passengers allowed the children, elderly, and pregnant women to stand on the seats. One group managed to break a glass window near the top of the first carriage, to allow more air into the train.

Outside the subway, rescue workers struggled to respond. This was partly a result of the scale of the disaster: Zhengzhou’s emergency 120 hotline, which had 11 staff members on duty that night, was receiving calls for help from all over the city.

But internal communication issues inside the subway stations also appear to have hampered the response. A local resident surnamed Zong rushed to Shakoulu station after discovering that his wife was trapped inside the Line 5 train. However, when he arrived at the station just after 7:30 p.m., the staff appeared unaware of the situation inside the tunnel, Zong told local media.

By this point, some passengers had managed to reach Shakoulu via the emergency walkway, and the staff insisted that no more passengers remained inside the tunnel. Zong had to video call his wife to convince the subway workers they were mistaken.

“I knelt down and begged the metro staff to let me go down (into the tunnel), but it didn’t work,” he said.

The situation was direst inside the carriage where Wang and Zou were located. Because the train was stuck on a steep incline, the water level was even higher in the rear. By 7:30 p.m., it had almost reached the carriage ceiling, according to domestic media.

To save themselves, Wang and Zou decided to try and get out of the train. By clinging to some cables hanging in the tunnel, they hoped they’d be able to withstand the surging water and make it along the walkway to the station. Wang discarded his backpack, cell phone, and shirt, to allow himself to move more freely.

As Wang and Zou inched along the tunnel wall, floodwater roared past them like it was pouring through a burst dam, Wang recalled. Then, suddenly, Wang saw Zou slip and disappear into the rapids.

Wang went numb. He lost the ability to think and just gripped the cables as tightly as he could. He didn’t let go until a rescue party finally reached the stranded train. Survivors estimate the first rescue workers arrived at around 9 p.m.

That night, Wang said he repeatedly urged the rescue workers to search for Zou, believing he might still be alive somewhere inside the tunnel. But his pleas fell on deaf ears.

Two days later, the Zhengzhou authorities announced that rescue teams had saved 500 passengers and recovered 12 bodies from the tunnel. Zou, however, was still missing.

Convinced he might still be alive, Zou’s wife, surnamed Bai, traveled to Zhengzhou from Shanghai and desperately tried to persuade Zhengzhou Metro Group to continue searching for survivors. But the company didn’t agree to conduct further searches inside the tunnel until the night of July 22, more than 48 hours after the disaster.

On July 25, Zou’s body was finally found. Bai has demanded the company explain why it delayed searching for more survivors. She has yet to receive a response.

When contacted by phone, a staff member from Zhengzhou Metro Group told Sixth Tone the company was currently investigating its response to the disaster. “We will release the results of the investigation to the public when our work is completed,” she said.

Sixth Tone reached out to Zhengzhou metro staff on more than 10 occasions, asking to speak with workers who were on the flooded train and requesting further information about the company’s response to the accident. All of these requests were denied.

On Monday, the State Council, China’s Cabinet, announced it would also conduct an investigation into the disaster response in Henan province — the region where Zhengzhou is located — during the recent floods. It added that any instances of “dereliction of duty” would be punished according to the law.

Nine days after the tragedy, Sixth Tone revisited the area surrounding the Wulongkou rail yard. The scene was calm: The water had receded and the roads were busy once more. But the flood had also left several scars.

By the curb, several mud-stained vehicles sat abandoned, their open doors hanging like broken limbs. In the distance, a canal bridge was still covered with debris.

Near the rail yard, a local resident was scouring the area on a scooter. He told Sixth Tone he had revisited the roads between Wulongkou and Shakoulu three times over the past few days, trying to determine what had caused the deadly accident.

“All of us, my child and my family, we all take the subway,” said the man, who declined to be identified due to privacy concerns. “I have to do this. They must make changes and take precautions to avoid (similar disasters happening again) — even if they don’t tell the public the truth in the end.”

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that Zhengzhou received just under 550 millimeters of rainfall between 8 p.m. on July 17 and 8 p.m. on July 20. The real total was just under 620 millimeters. The text has been updated with the correct figure.

Additional reporting: Fu Beimeng and Chen Si; contributions: Bulbasaur (pen name of a Shenzhen-based transportation researcher); editor: Dominic Morgan.

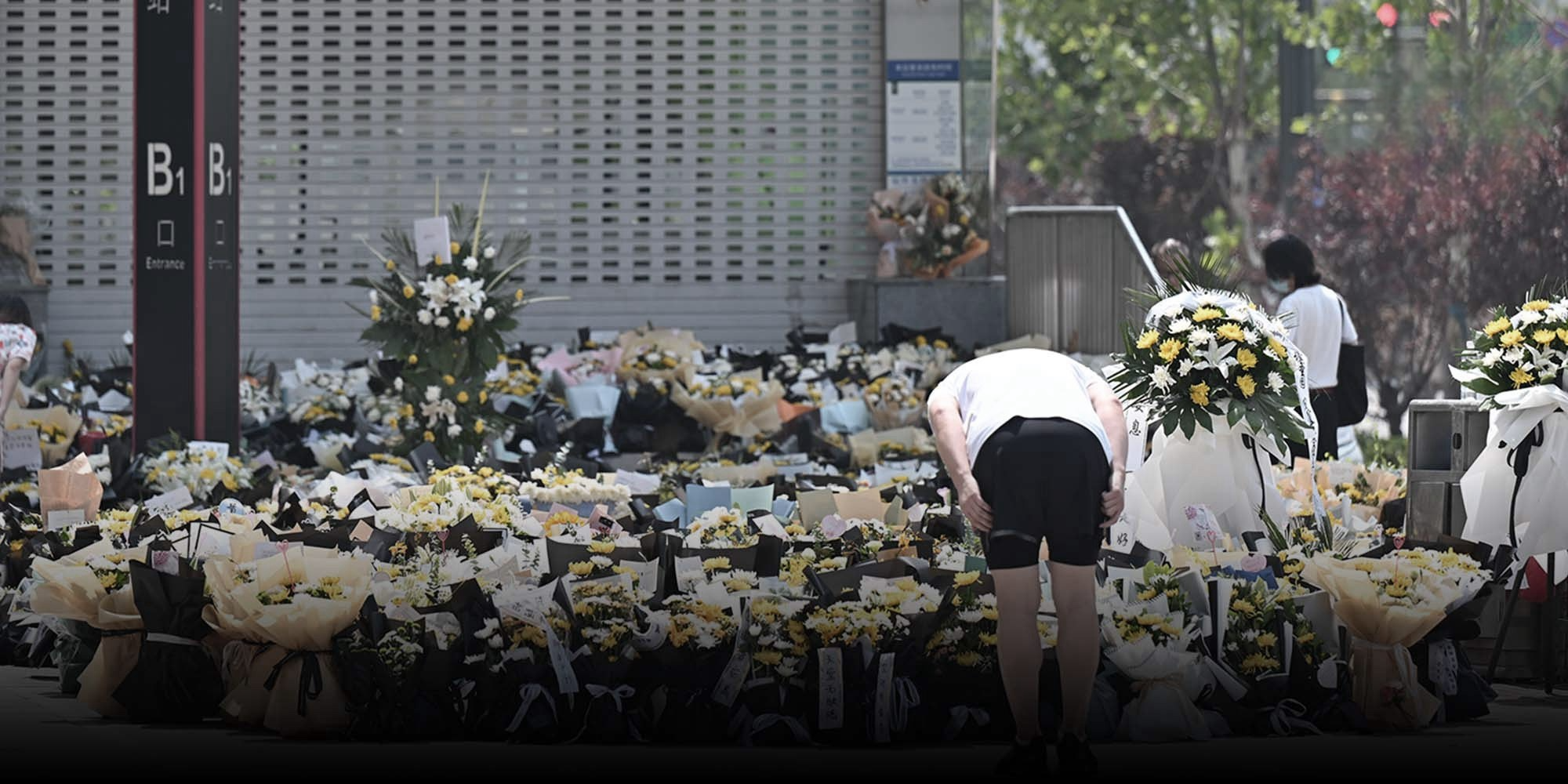

(Header image: People leave flowers and mementos to honor the victims of the tragedy in the flooded Zhengzhou subway, Henan province, July 27, 2021. People Visual)