China’s Sex Ed Classes Need to Teach More Than Fear

Sex education is finally on the agenda in China — sort of. Last October’s update to the Law on the Protection of Minors, for example, stipulates that “schools and kindergartens shall carry out age-appropriate sex education for minors, improving their awareness of and ability to protect themselves from sexual abuse and sexual harassment.” And at a March forum organized by the prestigious sex education organization Girls’ Protection, several deputies to the National People’s Congress and Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference proposed that sexual assault prevention be included in school textbooks and curricula.

There’s undoubtedly a real need for these measures. According to a recent report from Girls’ Protection, Chinese media reported 332 cases of sexual assault against minors involving more than 840 victims in 2020, and that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Yet it’s also worth noting what isn’t being talked about: sexual health and well-being in the broader sense, let alone contentious topics like homosexuality. With sexual behavior and sexual diversity still too sensitive to teach, the only knowledge about sex many students receive revolves around preventing sexual assault.

The rules about what can and can’t be said in sex education are reflected in Girls’ Protection’s own teaching plans and demo classes. These contain no description of sexual anatomy, such as the penis, breasts, or vagina; no mention of sexual acts like vaginal penetration; and certainly no discussion of sexual orientation. For example, in teaching students about anatomy, the teacher is told to lead the class in pointing out the ears, nose, legs, and other parts of the human body. But when they reach the sex organs, the teacher is to show a picture of a boy and a girl, dressed in blue and pink underwear, respectively. The genitals — covered as they are — are euphemistically referred to as the “private parts,” and even though the teacher is supposed to emphasize that they are “just the same” as any other part of the human body, no pictures are shown, nor are their actual names mentioned.

Naturally, there’s also no introduction to sexual activity. Children are instead taught to protect themselves from having their private parts touched and how to deal with “bad people.” The consequences of not protecting against these “bad people” include being “abducted, kidnapped, drugged, and killed.” By the end of the course, the students likely won’t understand much about sex, but they will have a solid education in the dangers lurking out there in the world.

All this may be helpful in protecting kids from sexual assault, yet that protection isn’t based on understanding, but fear. Sex is reduced to its risks, harm, and consequences, with none of its positivity and beauty. Meanwhile, what’s not talked about is just as telling, as this silence implies that the topic being avoided is wrong or abnormal. For instance, when sexual organs are not referred to openly like other body parts and when discussion of sexual behavior is avoided, the message kids receive is that sex is a sensitive or shameful topic. In a 2014 open letter calling for a less sex-assault-centric approach to sex education, the Chinese scholar Fang Gang shared the story of a teacher who asked middle school students what ideas the term “sex” conjured up. Most wrote down words like “rape,” “sexual harassment,” “pain,” “nausea,” “pregnancy,” “sexually transmitted diseases,” and “abortion.” Not one of them mentioned pleasure, joy, love, or intimacy.

A similar atmosphere once prevailed in Western classrooms. In 1988, the American scholar Michelle Fine published a research article in the Harvard Educational Review analyzing the mainstream discourses around sex education in American schools. She found that the discourses around sex often revolved around violence, victimization, and individual morality. Women were presented as vulnerable prey, and there was little discussion of desire, much less women’s desires.

This single-minded focus does a disservice to students. According to a 2008 survey of middle school students in New Zealand conducted by the academic Louisa Allen, the topic students most wanted to see added to their sex education curriculum was “how to make sexual activity more enjoyable for both partners.” In the survey, some students said that their teachers never used the word “orgasm” in sex ed class, and that sexual pleasure seemed to be treated as a bad thing. The New Zealand Ministry of Education’s 2020 update to its national Relationships and Sexuality Education curriculum now specifically states that sexuality education should not be framed by notions of risk and violence. Instead, it should focus on helping students develop the necessary skills and knowledge to have positive intimate relationships.

Underlying this shift is a broader critique of the overall goals of sex education. Mainstream classes on sex in many nations now seek to frame sexual health and well-being in a far broader perspective, including emotions, psychology, sexual rights, and social norms. Even the term “sex education” is falling out of use in favor of the more expansive “sexuality education.” In this framing, students are regarded as legitimate sexual subjects, able to weigh the pros and cons and make their own judgments and decisions in different situations.

Regrettably, China’s practices and policymaking concepts in the area of sex education have not yet caught up with these new trends. But there are hints that things are moving in the right direction.

Some Chinese academics have already expressed concern about sex education’s focus on preventing sexual assault. Prominent Chinese scholars of sexuality like Li Yinhe and Pei Yuxin signed Fang’s petition for comprehensive, “empowering” sex education in 2014. And in 2017, Liu Wenli, a professor at Beijing Normal University, compiled a series of educational textbooks for elementary school students entitled “Cherish Life” that included pictures of sexual organs and information about sexual behavior and sexual orientation.

Unfortunately, Liu’s work was withdrawn from circulation after it sparked backlash, which raises another question: Is it realistic to expect Chinese schools to immediately adopt mainstream international ideas on sex education? And might academics be overlooking the real difficulties schools have in setting up and promoting sex education classes? In an interview with a domestic media outlet, the head of Girls’ Protection acknowledged that, even without mention of sexual acts or naming the “private parts,” the group still faces considerable resistance from parents and school administrators. The organization’s curriculum is as much a product of compromise between the differing interests of these groups as anything else.

Still, sex education practitioners and policymakers don’t have to accept this compromise. If discussions of sex are silenced in sex education, or if sex education curricula unwittingly reproduce gender and sexual inequality, then what’s the point?

China’s initial forays into the field of sex education are a welcome and positive sign. However, it’s also important to realize their limitations, and to promote more comprehensive and more empowering sex education for young people. Only then can the country eradicate gender stereotypes and shift the focus of discourse surrounding sex away from violence, disease, and reproduction and toward pleasure, intimacy, and equality for all.

Translator: David Ball; editors: Cai Yineng and Kilian O’Donnell.

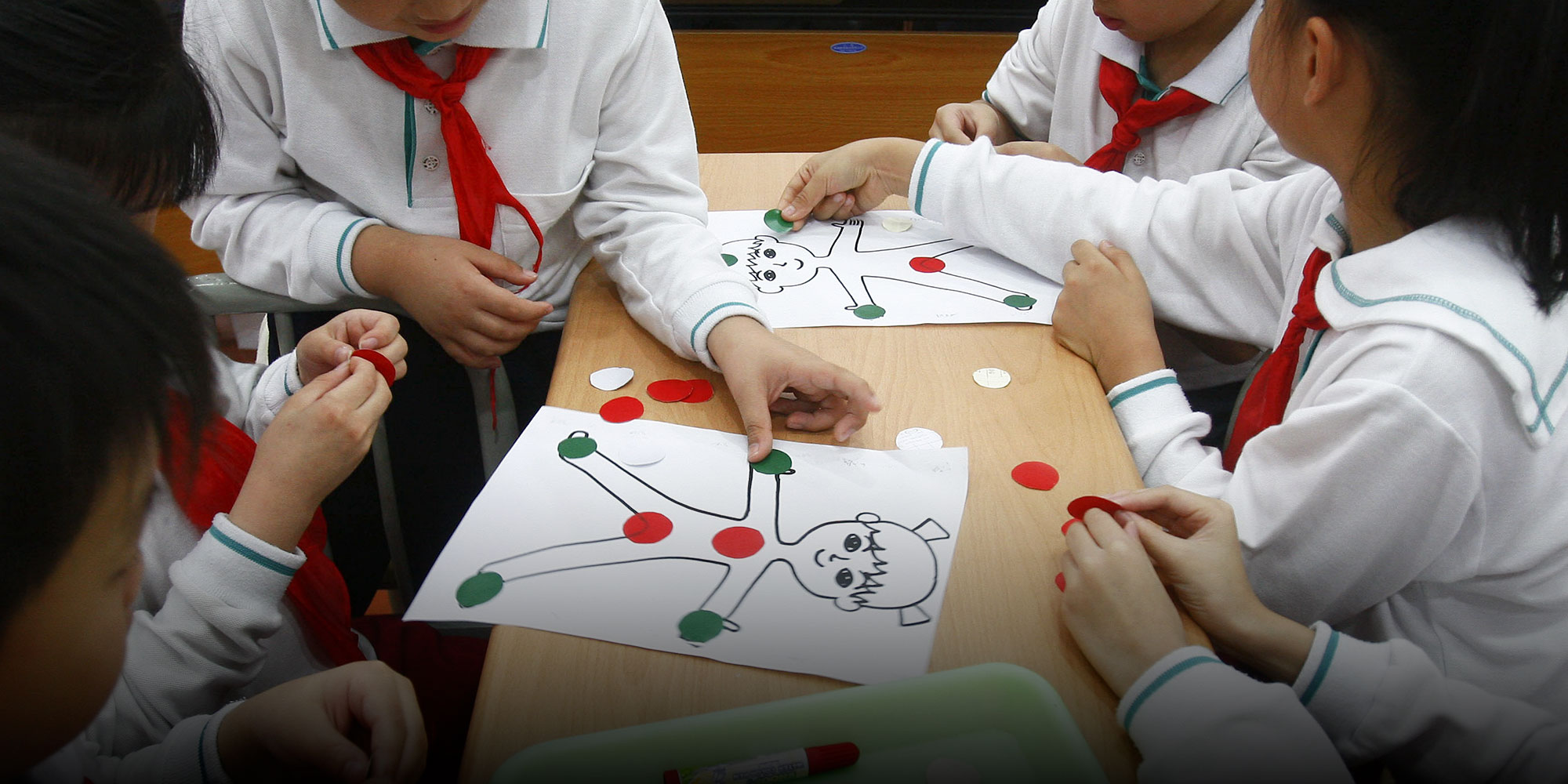

(Header image: Students take part in a sex education class at a primary school in Shanghai, 2011. Yang Yi/People Visual)