In Datong, a Crumbling Legacy of China’s Most Extreme Urban Makeover

This story is part of a weekend column featuring translations from respected Chinese media outlets, as selected and edited by Sixth Tone. All are reproduced with the outlets’ permission. A version of this article was first published in China Newsweek.

SHANXI, North China — Looking out over the city center of Datong, past the Temple of Confucius and the Temple of Emperor Guan, you can just make out a run-down area of ramshackle houses, their roofs mostly collapsed. Lü Laxi, 66, and his wife are among the few locals still living there.

Inside a square, single-story courtyard, the couple occupy a small room they bought in 1987 for 3,000 yuan — now about $440, then equivalent to nearly three years’ salary for Lü. Though not particularly luxurious, their home was located in the city center, a lively area close to good schools. “Every evening, people would sit outside our window playing cards by the light of the street lamps,” Lü remembers fondly.

Located about 250 kilometers west of Beijing, Datong is a small city by Chinese standards: Currently, Pingcheng District, which covers most of Datong proper, has 807,000 residents. But the city’s people could take pride in Datong’s rich coal seams and richer history.

When Lü moved from the countryside to Datong, the city’s historical center was still mostly recognizable as such, with many typically northern Chinese courtyard houses like Lü’s and other buildings from the days of imperial China, surrounded by imposing if not intact city walls. Five years earlier, in 1982, China’s central government had included Datong on its first-ever list of “National Historical and Cultural Cities” — no small honor for the hardscrabble coal town.

Decades later, Datong’s historical heritage would inspire a new, ambitious mayor, Geng Yanbo, to draw up grand plans to tear down and remake large parts of the city center. In 2008, work began to rebuild all manner of centuries-old buildings in a dramatic bid to steer the local economy away from coal and toward tourism. Thousands of homes would have to make way, earning Geng the nickname “Demolition Mayor.” More than 3 square kilometers of Datong’s city center became a giant construction site.

Though large-scale and controversial redevelopments are common for historical Chinese cities, Datong’s presented an extreme example. When Geng’s mayorship ended in 2013, he left a half-finished city center and a complicated legacy. To critics, the city had spent enormous sums of money without much to show for it. Today, 12 years after work began, Datong’s historical center still presents a headache for the local government. The impact on residents had been greater than anticipated.

“There used to be around 100,000 people in the old city, and at the time, the plan was to retain 30,000 to 50,000 residents. ” said An Dajun, the former leader of Datong’s People’s Congress — the local city council — and current head of the NGO Datong Cultural Heritage Conservation and Research Society. “No one expected numbers to fall to what they are now, fewer than 30,000 people,” he said. The former official also told China Newsweek that everyday life in the old city, with facilities such as hospitals and schools having been moved out, is difficult.

The courtyard where Lü and his wife live was once home to seven families, but today only two are left. Most have bought new homes and moved away. The erstwhile liveliness has given way to eerie calm. When night falls, all Lü can hear is the sound of dogs barking in the distance.

Replacing Real With Fake

In March 2019, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development and the National Cultural Heritage Administration published a criticism of five cities including Datong, stating that their “historical and cultural heritage has been severely damaged, and their historical and cultural value has been severely affected.” Datong, it said, had committed “wide-scale demolition and construction in the old city ... and the demolition of old buildings which have been replaced by fake structures.”

Though such issues have been widespread in China, the central government has gradually moved to protect the country’s ancient cities. In 2012, the two government bodies had put eight localities on notice over similar issues. Now, though, they went a step further: Datong was told to rectify the situation within three years, or the two government bodies will request that the State Council — China’s Cabinet — revoke Datong’s title as a National Historical and Cultural City. The city’s grand plan to build up a tourism industry is at risk of becoming its own undoing.

The bodies’ main criticism revolves around the reconstruction of Prince Dai’s Residence, a stately complex that was first built during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), but which had disappeared by the Qing dynasty (1644-1912). Demolition work to make way for a replica began in 2010. Together with restoring the giant Ming-era city walls and their countless towers, rebuilding the sprawling residence was a key part of Datong’s rejuvenation. Local media have dubbed it the “Little Forbidden City,” a reference to the former imperial palace in Beijing.

“After it was rebuilt and restored, experts raised issues with it,” Chen Ying, head of conservation and planning at the Datong Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau, told China Newsweek. Chen explained that after receiving last year’s criticism, Datong invited a team from Beijing’s prestigious Tsinghua University to compile a report on how to rectify the situation. The scholars concluded that Datong’s plan had been misguided from the start. Though the old city was being filled with replicas of Ming- and Qing-era buildings, Datong’s historical value was not connected to these dynasties. “Datong was the capital of the Northern Wei dynasty (386-534 A.D.) — that’s why it’s a famed city,” Chen said, citing the experts’ opinion.

Rebuilding the residence also came at the cost of demolishing existing historical homes. According to records, the old city was made up of “four main streets, eight lanes, and 72 alleyways.” Incomplete statistics show that more than one-third of the streets and lanes with their adjacent buildings have completely disappeared since 2008. Though the government’s plans include “restoration of old dwellings,” in practice such houses are torn down to make way for modern facsimiles.

Prior to the two departments announcing their criticism in 2019, Datong had kicked off a new, 12.5 billion yuan “revitalization project” that involved constructing more replica buildings. But the central government’s criticism and threat to revoke its National Historical and Cultural City status shook Datong. “This title is extremely important to us,” said Chen. All demolition and construction projects already underway in the old city were stopped until plans could be amended.

Decades of Destruction

The criticism was met with some grumbling in Datong. One expert, who did not want to criticize the central government on the record, said the evaluation process had been inadequate. “Whether the old city has been destroyed requires administrative investigation and assessment, and the opinions of local experts,” he said. “At the very least, the solicitation of opinions has not been fully carried out.” But others say the rectification demands have also spurred a healthy reckoning of Datong’s modern history of urban redevelopment.

Zhang Chengfu, an architect who specializes in historical structures, has made a detailed record of all the buildings that have disappeared in Datong. Practically every 10 years, the old city suffered a new round of destruction, he told China Newsweek. In the 1950s, Haihui Hall and the Bell Tower were both demolished. The local government also tore down four memorial arches in the center to ease traffic. In the ’60s, the South Gate and Wenchang Pavilion were knocked down. In 1979, the final surviving gate tower in the south and its connecting road that soldiers and their horses used to climb the city walls were also razed.

These structures were of unique historical and cultural value. “Take Haihui Hall, for example. (Famed architectural historian) Liang Sicheng identified a unique single-eave overhanging gable roof here,” Zhang said, his tone tinged with regret. Although the old city had been battered and bruised, enough history had survived for Datong to receive its coveted title in 1982. However, the 1990s, the second decade of China’s marketization drive, saw a nationwide tide of urban development.

In Datong, the municipal government wanted to build four thoroughfares through the old city, as well as replace all courtyard homes with six-story apartment blocks. The plans had popular support. Datong resident and bank security guard Ma Bin’s courtyard was torn down in 1998 to make way for an apartment block in which he still lives. “Our single-story houses weren’t worth a thing,” he told China Newsweek. “Everyone thought it was better to live in an apartment, so everything went very smoothly.”

Proponents stress that, at the time, the local government was short of funds. Zhang Weng, deputy head of the Datong Urban-Rural Planning Committee, told China Newsweek that despite the city’s reserves of “black gold,” little of the revenue from coal mining found its way into local coffers. Moreover, the incorporation of seven poverty-stricken counties into Datong’s jurisdiction put pressure on the city’s finances. Against this backdrop, Zhang Weng believes that projects to improve the city’s roads and people’s living conditions were entirely reasonable.

But conservationists called for immediate action to preserve the old city. In 1998, An became director of the Standing Committee of the Datong Municipal People’s Congress and started formulating laws and regulations to protect the old city. The headstrong director managed to halt the transformation before it became total. Nevertheless, the old city had changed beyond recognition. Nearly half of the kilometers-long old city walls were demolished, as were thousands of courtyard homes.

Such projects have been condemned by experts, too. Ruan Yisan, a professor of urban planning at Shanghai’s Tongji University who often advocates for protecting China’s historical buildings, wrote in an article: “What we refer to as ‘constructive destruction’ has occurred in the building of towns and cities across China since the 1980s and ’90s. During this time, most people, including leaders in many towns and cities, have lacked an understanding of historical and cultural heritage, blindly replacing old with new. They all say this is in order to meet the demands of construction and solve the problems of ordinary people’s living conditions, but they either neglect or don’t understand the significance of protecting cultural heritage, and have ended up causing irreparable damage.”

The Demolition Mayor

In 2008, the old city of Datong was already a product of conflict between those advocating conservation and development. But it would see even greater changes after the arrival of Mayor Geng that year. For better or worse, he would throw Datong into chaos. (His controversial tenure was the subject of a 2015 documentary, “The Chinese Mayor.”)

In his previous postings, Geng had already shown a passion for reconstructing historical buildings and old city districts. Urban renewal was his favorite governing tool. Two days after taking office in 2008, his first inspection trip was to Datong’s urban planning office, and not long after, he proposed his “one axis, two cities” concept: The old city would be restored, and to its east would rise an area called Yudong New District. The Yuhe River running between them was to be the “axis” between tradition and modernity.

Geng’s ambitious plans for the old city were initially questioned because of the large-scale demolition they entailed. According to the Datong Daily newspaper in 2016, the project to restore the old city walls alone took eight years and involved the relocation of 23,000 residents. The concept of reconstruction has also been criticized. “Historical objects cannot be reconstructed. The most basic tenet of protecting historical and cultural heritage is authenticity,” Ruan the professor told Oriental Outlook magazine in 2011. “What they’re building right now is a theme park.”

In February 2013, shortly after securing a new term as mayor, Geng was unexpectedly transferred out and appointed deputy party secretary of Taiyuan, the provincial capital, and soon after became its mayor. When he left Datong, all the construction sites fell quiet. The city wall still had a 185-meter gap on its western side. It wasn’t until 2015, when Zhang Jifu, then party secretary of a district in Beijing, was appointed party secretary of Datong and put in charge of finishing the walls, that work resumed. Locals who had grown cynical about the restoration project referred to this two-year pause as the “empty-window period,” a Chinese phrase for the time between breaking up and starting a new relationship.

Many reports at the time said Geng’s old city project had left the Datong government in debt to the tune of several billion yuan. However, An of the People’s Congress said this is overblown — that a majority of the roughly 70 billion yuan spent went to Yudong New District, with just 5 billion yuan going to the redevelopment of the old city. An explained that, early on, the municipal people’s congress did not want to go into debt, so it proposed funding the old city’s redevelopment with the proceeds of land sales in Yudong New District.

Nevertheless, when Geng left, the city owed some 20 billion yuan. His successor, Li Junming, noted in his first work report that Datong’s “cash flow problems are increasing by the day,” and that “the government’s debt risks must not be underestimated.” Under Li, the city focused on managing its debts, repaying more than 7.5 billion yuan in principal and interest in 2013 and 2014.

Despite it all, support for Geng can still be heard all over Datong. “Before Geng arrived in Datong, the city was unbearably dilapidated, and the people were listless,” said Zhang Weng of the planning committee. “Geng picked the city up from rock bottom. Residents discovered that our city still had a future.”

Finding a Fix

In Datong’s modern history, how to fix the city’s flaws has often been mired in institutional constraints and infighting between different government departments. Zhang Weng told China Newsweek that one such attempt in 2000 resulted in a deadlock between the municipal government, which wanted modern developments, and An’s people’s congress, which wanted to preserve the historical city center.

An was the main backer of the first set of regulations for preserving the old city, and his side of the debate has recently managed to draw up and promulgate an updated version. Two decades after the original, Regulations on the Protection of Datong Old City came into effect on Oct. 1, and include more specific protection measures.

Some bureaucratic maneuvering has taken place to bring the various sides together. “We have established a leading group and old city management committee to coordinate all parties,” Wu Baozhou, deputy head of the Datong Municipal Old City Protection and Development Leading Group, told China Newsweek. But the committee, established in 2017 and headed by Wu, has proved ineffective. It has been demoted in the official hierarchy from a city- to a district-level committee, lacking executive authority. The committee is in the process of applying for the old city to become a “provincial-level model ecological cultural tourism district,” which would bring enhanced administrative powers. In addition, an Old City Investment Group will be established this year to aid the construction work.

In the meantime, many of the remaining historical houses in the old city that were abandoned during the myriad redevelopment projects have collapsed, meaning restoration is no longer just a matter of patching up the roofs, according to Zhang Weng. “This kind of restoration work is very difficult,” he said. “We need to find a technological solution, no matter how difficult.”

Large tracts of land within the city walls, razed at some point in the past decade or so, still lay bare, such as the area around Prince Dai’s Residence. In 2019, there were plans for commercial and residential projects around the residence worth billions of yuan. But after the central government’s criticism, they were put on hold.

Another planned residential area next to Huayan Temple has also run into bureaucratic difficulties. Huayan Temple is one of the oldest and best-preserved temple complexes in China, dating from the Liao and Jin dynasties, between the 10th and 13th centuries. In 1961, the State Council named it among the first batch of “national key cultural relic protection units.” To its south, the city wants to build new courtyard houses where old ones once stood. But because of the temple’s lofty status, any nearby projects need central government approval. In February, the National Cultural Heritage Administration rejected the proposed plans, saying the city’s design did not properly reflect the area’s history, and requested that revisions be made.

“The redevelopment of the old city cannot be reversed,” Lin Lin, director of the Historical and Cultural City Planning and Design Center at the Shanghai Tongji Urban Planning and Design Institute, told China Newsweek. “Once you begin, you can never go back to the way it was: You can only continuously improve it. This is a possible path. But right now, there seems to be no direction.”

Translator: David Ball, editors: Yang Xiaozhou and Kevin Schoenmakers.

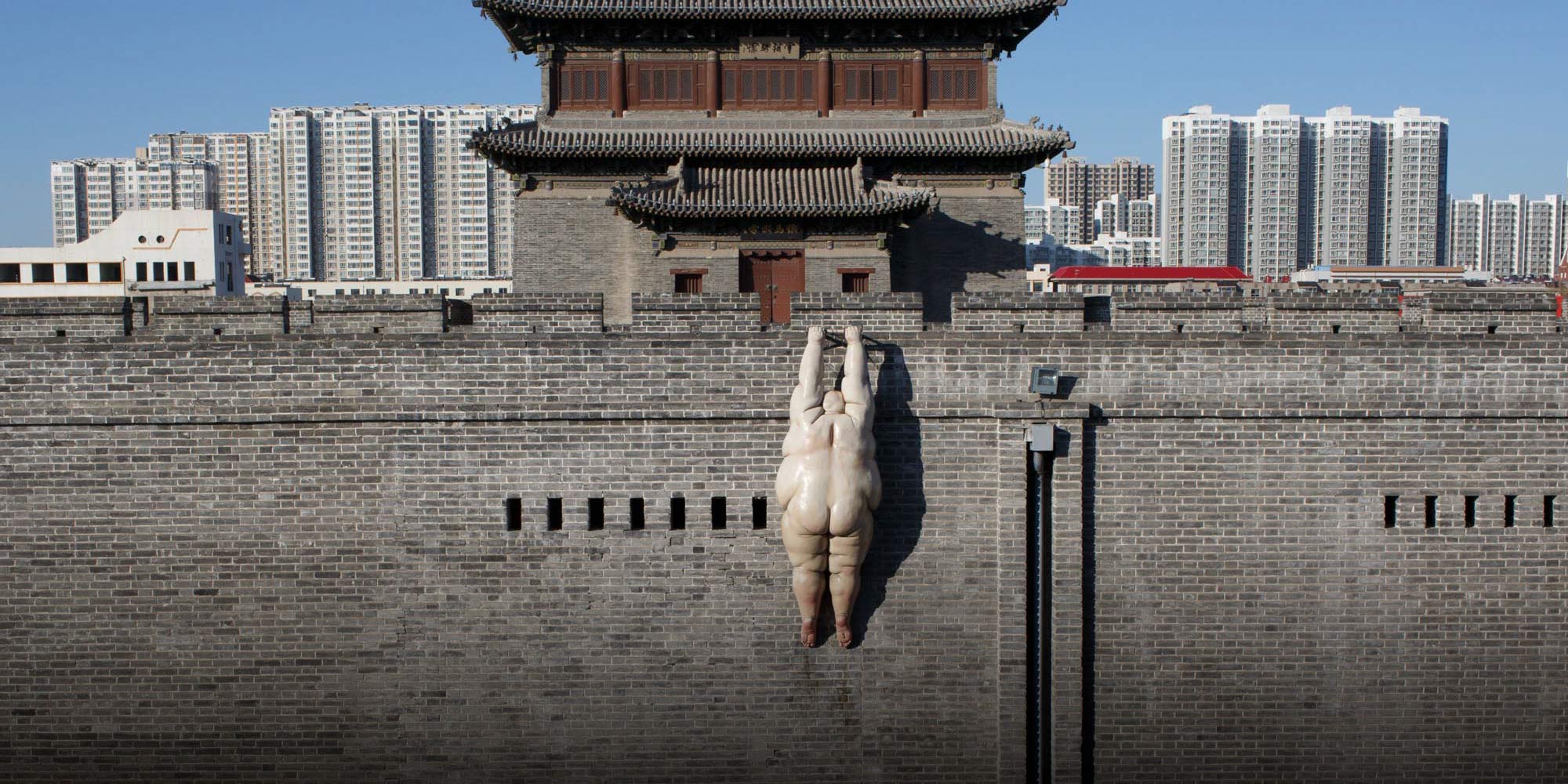

(Header image: A statue hangs from the city wall of Datong, Shanxi province, Nov. 2, 2016. Zhou Pinglang for Sixth Tone)