The Artist Giving China’s Ghost Villages a Second Life

The houses’ furniture has been cleared away, and the walls mostly stripped bare. All that remains are the items the families left for the bulldozers.

In one room, a stuffed toy crocodile spills from an open suitcase, as if the owners had suddenly abandoned their attempts to cram it inside. In another, a pair of sandals sits forlorn under a banner displaying the Chinese character for “double happiness.”

The poignant scenes are part of “The Entrance Hall,” a photography series by artist Guo Guozhu documenting the destruction of a village in eastern China during an urban development project.

In February 2015, a cluster of traditional residences on the outskirts of Hangzhou were torn down to make way for a new retail and residential complex, with the displaced residents sent to live in apartment blocks across the city. Before the demolition crew arrived, Guo went from house to house, snapping the interior of each condemned home with his camera.

The project aims to capture the sense of rupture and loss that haunts communities uprooted during China’s massive urbanization drive, which has seen the number of city dwellers rise from 170 million in 1978 to 830 million in 2018.

Moving into the cities has brought many former villagers unprecedented wealth, but also feelings of dislocation, according to Guo. The atomistic, competitive lifestyle prevailing in urban China alienates many from the more communal countryside.

“You’re definitely familiar with your neighbors in the village, but not necessarily in the city,” Guo tells Sixth Tone. “You may not even know who lives opposite you.”

The photographer has personal experience of the cultural divide between rural and urban China, having grown up in a remote mountain village in the eastern Fujian province. He describes his hometown as a typical rural community — an “acquaintance society” in which families were extremely close-knit, everyone knew each other intimately, and privacy was almost nonexistent.

For Guo, the most powerful symbol of this acquaintance society is the entrance hall — a common feature of rural Chinese homes that serves as the focal point of family life. Households use these front rooms to hold ceremonies to honor their ancestors, conduct family meetings, and host guests.

“You often put two or three tables in the entrance hall and invite many friends and relatives over to have a meal and drinks,” Guo tells Sixth Tone. “Especially if there’s something important (to celebrate) in your home — like if you buy a car.”

When Guo visited the condemned village in Hangzhou, his lens was continually drawn to the houses’ entrance halls. His images often provoke a sense of melancholy — the abandoned objects hinting that not only a home, but also an entire way of life has been left behind.

The 38-year-old shows Sixth Tone a portrait of one room in which the floor is covered with piles of dishes and bowls. The former occupants likely knew, he says, they’d never host so many guests in the city.

The divide between urban and rural, Guo suggests, is often not so much geographic as cultural and psychological. After the village in Hangzhou was redeveloped, many of the former residents moved into apartments in the new high-rises — a relatively common phenomenon in China. But the relocations are still jarring.

Though displaced residents often end up living within a few kilometers of their former homes, they can feel forced to swap one identity for another — a process that can be traumatic. In a surprisingly large number of houses in Hangzhou, Guo says the former residents had left behind their family photo albums, as if they’d accepted the need to start over completely.

“We must have a strong adaptability to deal with breakneck development,” says Guo. “It leaves bloodstains and wounds on each of us.”

Guo carries his own psychological scars, after struggling to adapt to city life in his youth. As a boy growing up in Fujian, he recalls the move to the city feeling like a lofty, but distant dream.

“Our image of urban life was shaped by Hong Kong-made movies and TV series, where every character has a magnificent career,” says Guo.

Life in the close-knit village, though warm and comforting, could also feel claustrophobic and restrictive. In the ’90s, one young man Guo knew was caught taking his girlfriend up the mountains to take nude photographs. The scandal haunted the man for years, affecting his career and reputation in the community.

“People kept gossiping about this young man in a way that made him unable to keep his head held high,” says Guo.

When Guo was in ninth grade — the final year of schooling in the countryside — the fear of being stuck in a rural community ate away at him. After years of slacking off, he studied furiously to make sure he got a place at an urban high school.

“I suddenly realized if (I failed), I’d have to learn carpentry with my dad,” says Guo. “I felt a little flustered at the thought of spending my life in the mountains as a carpenter.”

When Guo enrolled in a high school in Yongchun County, a conglomeration of small towns near his home village, he remembers being surprised to discover his 30 classmates all had different surnames. “We all have the same two surnames (back in the village),” says Guo.

Eventually, he gained admission to a college in Nanchang, the capital city of the eastern Jiangxi province. On weekends, he’d take his camera downtown and photograph the skyscrapers and enormous train stations like a tourist. But he was already beginning to feel disillusioned with city life.

“It may have many historical monuments, but the urban landscape in Nanchang wasn’t particularly good,” says Guo. “It didn’t match my imagination.”

After college, Guo landed a job at an industrial firm in Xiamen, a more modern and prosperous city on China’s southeastern coast. He finally started to feel like a true urbanite, but he also had to face the harsh realities of city life.

Most shocking of all was the moment Guo learned the price of an apartment in Xiamen. Owning a home is essential for migrant workers in China, he explains. Unless you’re a homeowner, it’s difficult to find a partner and get married. Buying an apartment is also the easiest way to gain permanent residence in the city, entitling your future kids to places at local schools. But the extremely high real estate prices in China’s large cities are unaffordable for many on average incomes.

“People work hard all their lives to buy an apartment, living their whole life as mortgage slaves,” says Guo. “It even affects their children and their entire quality of life.”

In 2010, Guo realized there was no way he’d ever afford an apartment in the city, and he decided to resign from his job and become an artist. He moved back to the countryside part-time, setting his heart on turning his observations on China’s urbanization drive into an art project.

Guo sees echoes of his own experiences in the lives of the villagers in Hangzhou. He acknowledges the majority of them initially welcomed the demolitions. To many, the project signified a more comfortable life and new opportunities.

“Most people were actually very happy, because there was substantial relocation compensation,” says Guo, adding that households received up to 5 million yuan ($805,000) each.

Guo’s photographs of the villagers’ jettisoned belongings provide stark reminders of how much more traditional — and less prosperous — China’s rural areas are compared with its urban centers. An accompanying collection titled “Relics of a Village” portrays a series of objects that appear to be from another era: a portrait of Stalin, an analog radio, a set of candles used for ancestor-worship ceremonies.

Discarding the items may have felt liberating to some villagers, who longed for a radical break with their past, according to Guo. But the artist can’t help viewing the scenes through nostalgic eyes, as he’s aware of what was lost in the process.

“They’re actually more like portraits of the deceased,” says Guo.

In the years following the demolitions, many villagers’ fortunes dimmed, Guo says. To some, the million-yuan payouts ended up being a poisoned chalice. Relatives arrived demanding money to pay for medical bills. Villagers took to gambling. Others developed drinking problems. Within a year or two, the money was often gone.

“When I was observing on the spot, I already saw many tragedies happening,” says Guo.

After a decade as an artist, Guo admits his feelings toward the city remain conflicted. Cities promise comfort and riches. Yet they can also bring stress, disruption, and danger. Despite all his misgivings, Guo says he still rents an apartment in Xiamen and sends his daughter to school there.

In the meantime, the photographer is continuing his quest to capture the reality of urbanization in China — and preserve the memory of what was lost along the way.

Editors: Dominic Morgan and Shi Yangkun.

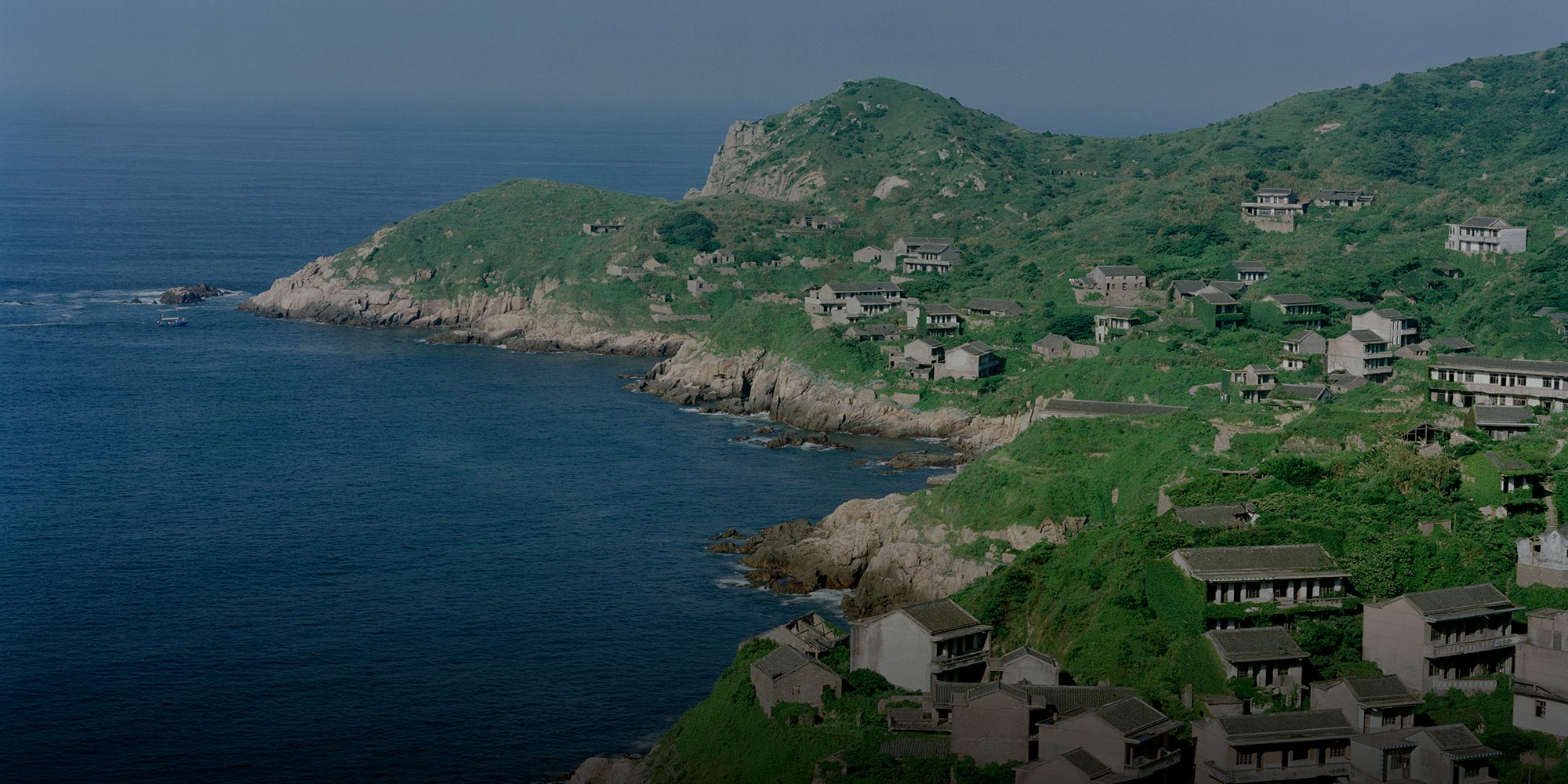

(Header image: “No.01︱122°82’E 30°72’N,” from “Lingering Garden,” 2015. Courtesy of Guo Guozhu)