China’s Web Fiction Writers Strike Over Copyright Confusion

After what has been called the most tumultuous week in the history of China’s internet literature industry, writers under the country’s largest online publishing group banded together Tuesday to protest potential changes to their contracts.

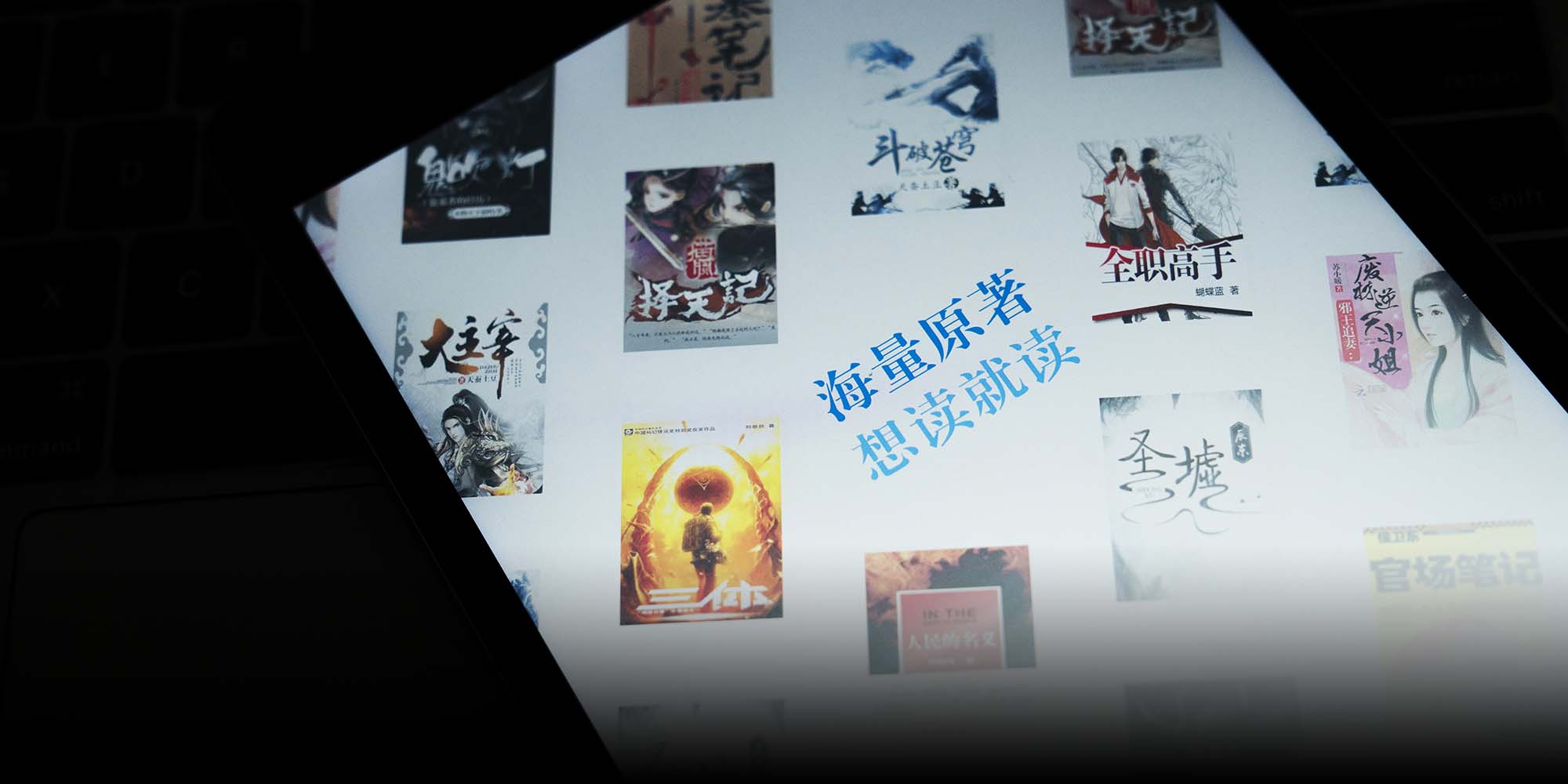

With one-quarter of the domestic market share, China Literature is the dominant player in the country’s online fiction industry. The Tencent-backed group owns several popular reading apps that are fed by an army of over 8 million “internet writers” — contracted authors of serialized web novels. In recent years, dozens of China Literature franchises like “The King’s Avatar” and “Ghost Blows Out the Light” have been successfully spun off as TV dramas, anime, video games, and movies.

The controversy began after a major management reshuffle at China Literature on April 27, when the group’s founding members collectively resigned and were replaced by Tencent executives. In the aftermath, rumors circulated that the old guard had resisted the group’s apps transitioning to free-to-read formats, according to Sixth Tone’s sister publication The Paper.

Tensions were exacerbated when an allegedly new contract with more stringent terms and conditions was widely shared among the group’s authors. According to screenshots of the document posted to social media, China Literature would own all rights to a writer’s works until 50 years after their death. The group would also be authorized to “transfer” the work of one writer to another, sell the rights to any work, or distribute it for free.

Other terms suggested that China Literature would have some authority over writers’ social media accounts, and that writers would have to cover their own legal fees in the event of a copyright infringement lawsuit.

The authors lamented that these changes would effectively turn them into ghostwriters for China Literature, enjoying none of the rights or privileges of regular employees.

“The new contract makes us authors feel like we’re just copywriters for the platform,” one internet writer told The Paper. “We lose our copyright, the right to know the makeup of our income, and the right to freely disseminate content on social media. This feels worse than being sold into slavery.”

To the writers, another vexing aspect of the new contract is the implicit transition to a free-to-read business model that would rely heavily on advertising. They fear this could lower their already-low incomes, which now mostly come from reader contributions and subscription fees.

From May 2, outrage over the contract trended on Chinese social media, with hashtags garnering millions of views and thousands of comments. The internet writers complained that the new contract was a prototypical example of the perils of market monopolies and the ugly face of capitalist exploitation — phenomena that the proletariat must resist.

“This is class struggle,” one writer commented under a related Weibo post. “The bourgeoisie and capitalists only pursue profits, their pores ooze dirty blood, they squeeze the proletariat for every drop of oil they can. ... Those who betray the people will find themselves nailed, by the people, to history’s pillar of shame.”

In the early hours of May 3, China Literature issued a statement that said the contract being circulated had actually been drafted and shared last September, and that the feedback received from it was being taken seriously. The group also said it was exploring various business models, and that transitioning to read-for-free was not economically viable at present.

However, the statement did little to assuage the author’s concerns. They responded with collective action, taking to social media and beseeching their peers not to post updates to their stories on May 5. To hype up the event, they shared posters featuring the date “5.5” and socialist imagery — fitting, given that the day before, May 4, is remembered as a milestone in China’s revolutionary history.

According to the internet writer who spoke to The Paper, the driving forces behind the strike were China Literature-affiliated writers who wanted to protect their intellectual property, as well as outsiders who encouraged authors to leave the group and start their own ventures.

On the day of the strike, some writers claimed that their May 4 story updates had been changed to read May 5, and story content they had saved as drafts was inexplicably published without their consent. Meanwhile, those who ignored their comrades’ call to arms and updated their stories as usual complained of being insulted as traitors to the movement.

After the taboo Tuesday, China Literature posted a list of rebuttals to some of the rumors that had been circulating, denying any timestamp tampering and promising to have an open discussion with the writers. And Wednesday afternoon, the group clarified that the terms in the old contract reflected industry problems dating from many years ago, and that the new management would have been hard-pressed to produce such a document so quickly after assuming control.

The group also said that the authors would have a say in how their works are used, and could have the option of choosing from among different kinds of contracts in the future.

To free or not to free — that is the question that has long created headaches for China Literature, according to industry commentators. In late 2018, a wave of free-to-read apps sprouted and quickly grew popular. Two have since risen to fourth and fifth place in terms of total market share. From 2017 to 2018, paid subscribers to China Literature’s apps fell by 1 million. The company is now largely preoccupied with creating popular franchises that can be adapted to TV and film, but this requires traffic.

Amid the chaos of the past week, some writers — notably the famous online author Zhang Wei, better known by his pen name Tang Jia San Shao — have called for calm, imploring the writers to give China Literature’s new leadership a chance.

“Authors are a resource, existing at the very top of the culture and entertainment industry chain,” Zhang wrote in a lengthy Weibo post. “I firmly believe that no leader will make decisions that will forsake these resources.”

Editor: David Paulk.

(Header image: The welcome screen for the QQ Reading app, operated by China Literature, is displayed on an iPad in Hong Kong, Oct. 25, 2017. Anthony Kwan/Bloomberg via Getty Image/People Visual)