It’s Time for China To Legalize Egg Freezing

Last December, 31-year-old Teresa Xu made international headlines when she sued a hospital in Beijing for violating her personal rights. Her cause? Doctors there had refused to help her freeze her eggs, citing national regulations that severely curtail unmarried women’s access to assisted reproductive technology (ART).

Xu’s ongoing case is the first-of-its-kind in China, but it is also the latest skirmish in a broader battle waged by Chinese women over reproductive rights. As more women put off getting married and having kids, many have come to view freezing their eggs as a sort of backup plan, or what advocates call “a medicine for regret.” But opponents, including many within the state apparatus, remain concerned about the potential impact on marriage and traditional family structures, as well as the social implications of a rise in single-parent families.

According to standards issued by what was the Ministry of Health — and is now the National Health Commission — in 2003, access to egg freezing technology is restricted to infertile married couples who are entitled to have children under China’s family-planning laws. This is broadly in keeping with the People’s Republic of China’s long-held stance that only legally recognized couples should be allowed to exercise their reproductive rights. Women wishing to freeze their eggs must present a marriage certificate, state-issued “birth registration form,” and ID card, and they must be able to show proof of infertility. Although there are exceptions to the law for single women diagnosed with cancer or other conditions that may result in impaired ovarian function, these are extremely limited in scope.

Ironically, while single women are prohibited from freezing their eggs, single men generally face no barriers to freezing their sperm. State-issued regulations designed to foster the development of sperm banks, also from 2003, explicitly allow men to “preserve sperm for use in fertilization in the future,” without needing to prove their marital status. There is no logical reason why men worried about fertility should be allowed to freeze their sperm while women with the same concerns are blocked from freezing their eggs, and many proponents of ART have used this discrepancy to argue that current laws unfairly restrict women’s rights.

The current rules aren’t only unfair, they are also over 15 years old and clearly out-of-step with some of the changes in Chinese society over the past decade and a half. Not only has the country gone from seeking to strictly limit births to trying to increase fertility — albeit within limits — shifting public attitudes toward love, marriage, and family norms mean fewer women consider staying single and starting a family fundamentally incompatible goals.

Other women, concerned about the so-called motherhood tax and focused on their careers, worry that having kids could set them back in the workplace. At least one major company has started offering to pay for some female employees to undergo egg freezing procedures abroad.

On a policy level, the former National Health and Family Planning Commission announced in 2017 that it was reviewing egg freezing technology. Proponents quickly renewed calls for the health authorities to allow the practice, and in 2018, the National Health Commission responded to a Shanghai-based lawyer’s pro-ART advocacy by declaring it would “increase research; gradually build a consensus; improve related laws and policy measures; and earnestly safeguard the rights and interests of women in reproduction, employment, and career development.” But these are just words, and there are as yet no signs of a policy or regulatory rethink at the national level.

Locally, there is one province on the Chinese mainland that allows women to freeze their eggs, at least on paper. Since 2002, regulations issued by health officials in the northeastern Jilin province have stipulated that “women who have reached the legal age of marriage, have decided not to marry, and have no children may have a child through legal medically assisted reproductive technology.”

Although this rule is clearly in conflict with current national statutes, it has survived unchanged for 18 years and withstood three provincial-level reviews. One reason is that it’s never been tested: There are no recorded cases of women taking advantage of Jilin’s law to freeze their eggs, likely because local hospitals and doctors are worried about crossing Beijing.

One of the key legal roadblocks to expanded ART access is the question of surrogacy. A hot-button issue in China, opponents and some policymakers worry about the legal, ethical, and societal impact of allowing the practice. In particular, China would have to determine the relative rights of any surrogate child’s biological and gestational mothers, as well as resolve thorny issues like inheritance.

In addition to the legal hurdles, some Chinese simply believe surrogacy goes against the normal reproductive order, runs counter to the public good, poses health risks, and could lead to the commodification of fertility. Others worry that children born into so-called incomplete families will be at a developmental disadvantage.

But surrogacy is a powerful tool for the realization of universal reproductive rights, and many countries and regions around the world have legalized it without undermining the social order. There’s a broader need in China for such services that goes beyond single parents and includes couples with fertility issues and aged shidu parents who have lost their only child.

If lawmakers are concerned that allowing single women to freeze their eggs will lead to uncomfortable discussions about sensitive issues such as surrogacy, then maintaining the current ban is undoubtedly their most labor-saving option. However, avoiding the problem doesn’t mean it ceases to exist. China is faced with an aging population, a trend toward delayed marriage and childbirth, and dropping fertility rates. If we truly want to resolve these issues and increase birth rates, perhaps we should start by freeing women to make the choices that are best for them.

Translator: David Ball; editors: Cai Yiwen and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhang Zeqin.

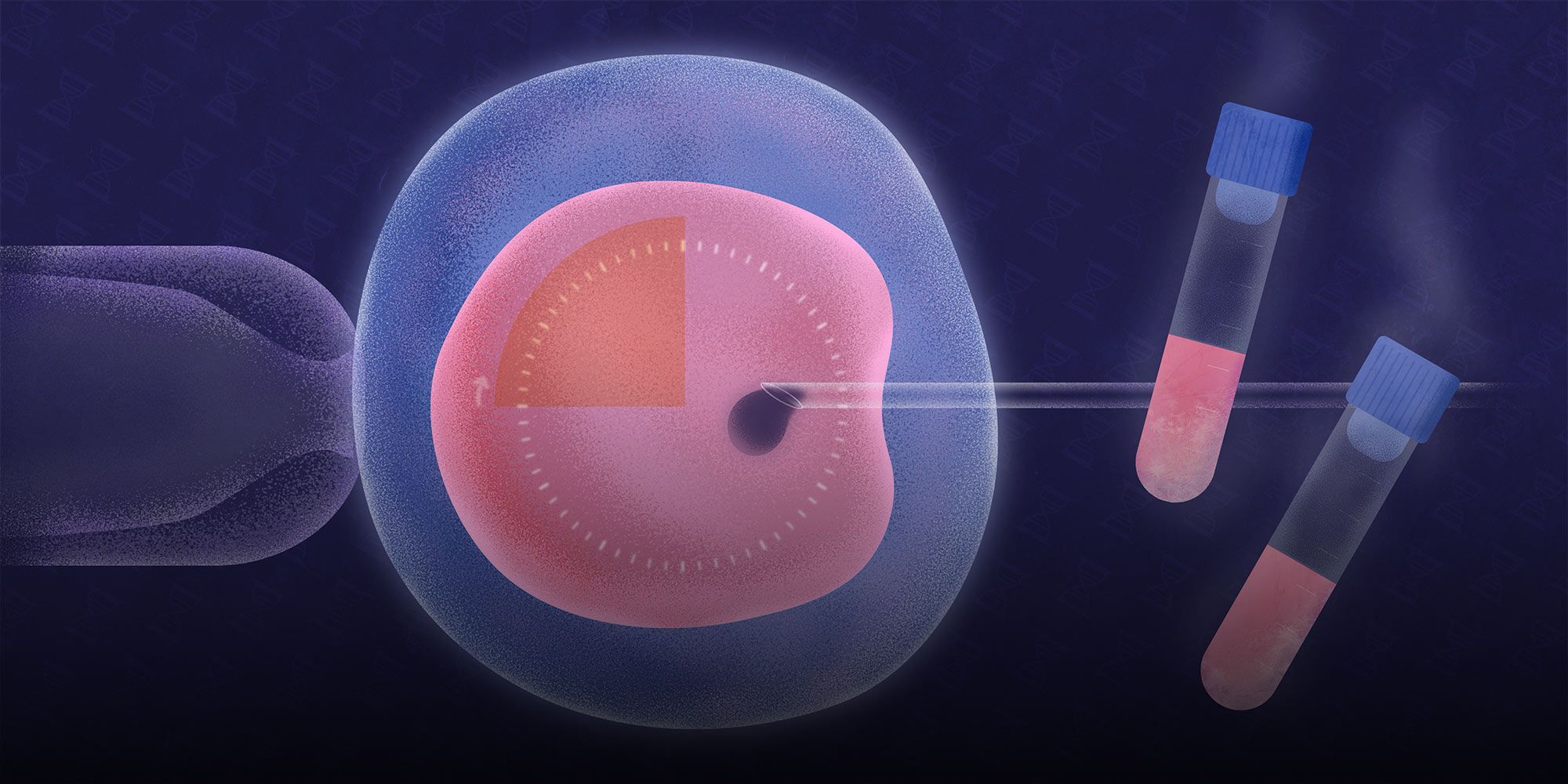

Header image: Fu Xiaofan/Sixth Tone