A Billion Homes: The Bittersweet Joy of Writing Home at Lunar New Year

This is the third article in A Billion Homes, a three-part series exploring the meaning of the Lunar New Year holiday for Chinese families across the world. Read part one and part two via the embedded links.

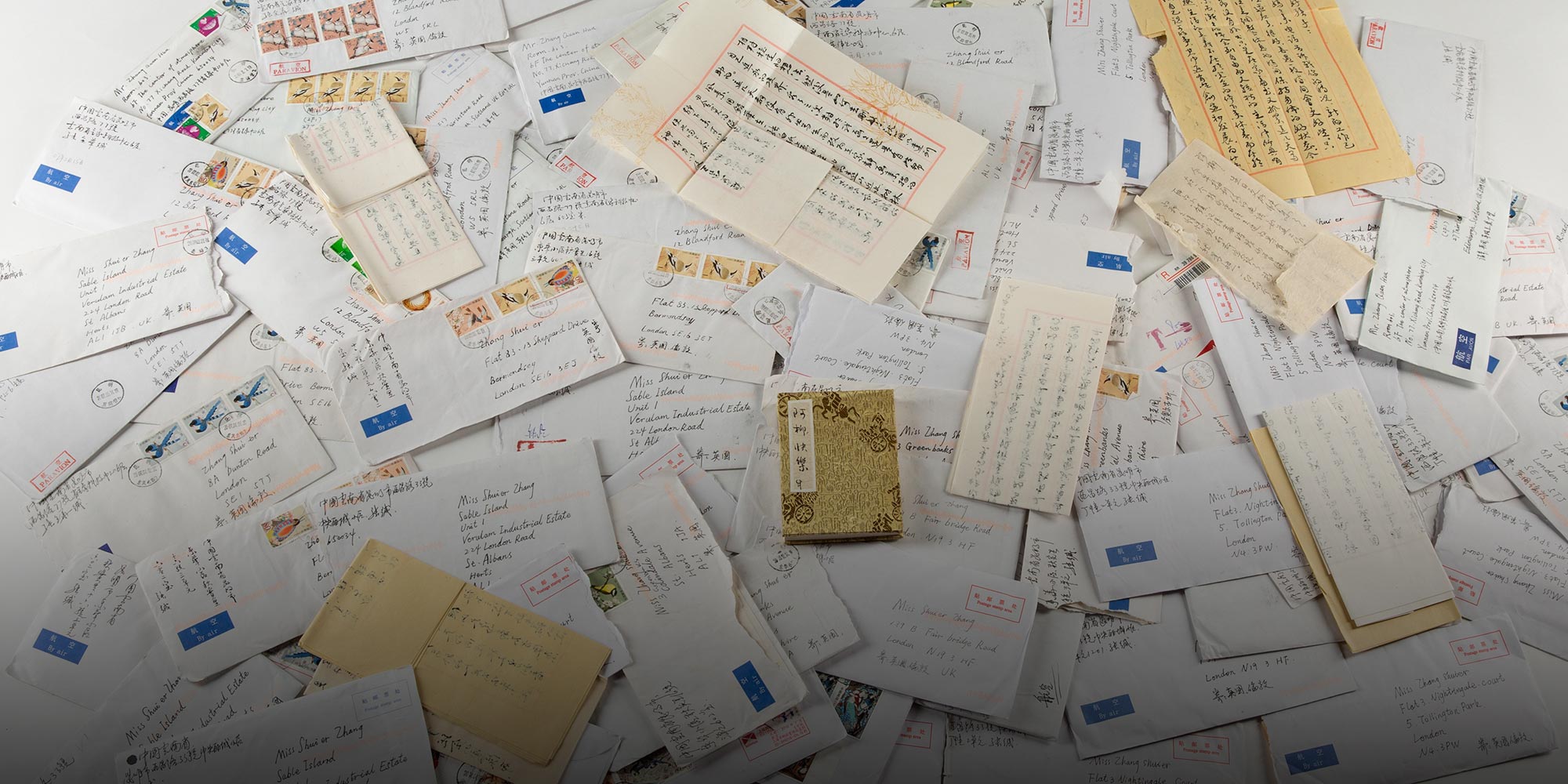

“Ah Liu, my dear child. This is my first letter to you, one that will travel an unimaginable distance — all the way to the West,” Zhang Shui’er read aloud. She’d pulled out a box full of letters and spread them across the kitchen table of her North London home, before picking up one from her father. As she continued reading, her voice started to crack.

This was my first time meeting Zhang — who prefers to go by Ah Liu, the nickname her father gave her. Originally from China’s southwestern Yunnan province, she had been living in the United Kingdom for a decade, working as a translator.

Ah Liu had contacted me in early 2016 after seeing a post I’d published on the social media app WeChat: “Friends in London, I want to give you a camera in exchange for your family letters.”

I wanted to find a handful of Chinese citizens living in the U.K. who would write to their families back home and document their own lives abroad for them, using the disposable camera I would send them. We would then mail the photos and letters to their relatives in China.

Classical Chinese poetry likens family letters to “tens of thousands of pieces of gold,” due to their essential role in maintaining ties between travelers and their kin. As I completed my master’s degree in documentary photography at the University of the Arts London, this phrase was often on my mind.

My homesickness had grown as Lunar New Year approached. I hoped the project would help me understand the root of this feeling, which many of my Chinese peers shared.

My post received numerous responses — all of them from women between the ages of 19 and 49. Many had heartbreaking stories they wanted to share. One had swallowed a bottle of sleeping pills in an effort to save her parents’ marriage. Another had sobbed inconsolably after missing her mother’s surgery. Yet another had been unable to visit her family in China for years, because she had to care for her ailing husband in the U.K.

Ah Liu was one of the participants. She had urged me to visit her in person, saying that her story would probably be of use to me. When I arrived, she produced a thick stack of letters. There were 107 in total, all written by her father in Yunnan between 2005 and 2015.

Ah Liu’s father had studied Chinese at university, and he penned his letters with care, using traditional letter paper bordered in red. His words, written in elegant Chinese characters, ran vertically, right to left. Every letter opened with the same greeting — Ah Liu, my dear child — before launching into a stream of reminders and advice.

On Ah Liu’s birthday in 2015, her father mailed her something special. He’d created simple traditional Chinese figure drawings in an orihon — a book with multiple, accordion-like folds — and transformed it into an illustrated book memorializing episodes from his daughter’s childhood.

After receiving her father’s letters, Ah Liu would always call or e-mail him, confessing that she could never match his letter-writing diligence. For her, writing him as part of my project helped fulfill a long-delayed promise.

Another respondent was Lan Lan, a 49-year-old from Shanghai who resided in a village in eastern England. She had been living in the U.K. for more than four years but had never been to London. She caught the early morning train, and we met at 9:15 a.m. beneath London Bridge before heading to a nearby café. For two hours, she poured out her story, barely pausing for breath.

Lan Lan’s first marriage had failed. But in 2006, when she was running a wine business in Shanghai, she met a Scottish man 17 years her senior. They quickly fell in love and married in 2009. When her husband’s company relocated him to Australia, Lan Lan went with him.

One day, while her husband was on a business trip to the U.K., Lan Lan received a call from one of his colleagues. He told her that her husband had suffered a heart attack and was in the hospital.

Lan Lan only had a Chinese passport at the time, so she had to apply for an expedited visa before she could fly to Britain with her son. By the time she arrived, her husband had already been discharged from the hospital.

Not long after, however, he was struck by another heart attack. Her husband had no choice but to retire early and return to the U.K. to recover.

“With my husband’s heart problems, depression, and alcohol dependency, he can’t take care of himself,” Lan Lan told me. “It’s been five years, and all of my friends — both in Australia and here — have pushed me to get a divorce.”

“But I won’t leave him,” she continued. “If I do, everyone — including my husband — will think that Chinese women just marry for a U.K. passport. I’m a Shanghai native. I have everything I need. I married him because I’m attracted to him. It’s that simple.”

Yet more than 9,000 kilometers away in Shanghai, Lan Lan’s 75-year-old mother continued to worry about her. Two years after Lan Lan moved to Australia, her father suddenly developed cancer and died, leaving her mother on her own in the city. In her letter to her mother, Lan Lan wrote:

Dear, Mom: Happy New Year! Both of us will have lonely New Year celebrations this year. You’re at home by yourself, while my husband’s minor stroke makes it hard for him to move around. His situation worsens by the day, but luckily our son is still around to keep us company. All of that just means I’m in no mood to make dinner on Chinese New Year’s Eve.

Her elderly mother had no desire to move abroad, but Lan Lan felt she couldn’t leave her bedridden husband’s side. She had no way to make everyone happy and felt guilty for not being able to see her mother. At times when she felt particularly down, she’d go to church and sit quietly by herself. Most of her time, though, was spent caring for her husband and son.

“My favorite work of literature is ‘Jane Eyre’ — I’ve read it about a dozen times,” said Lan Lan. “I envy her for finally finding her Rochester. Their house burned down, and Rochester went from being rich and handsome to being blind. It’s so romantic. I want to become a Jane Eyre.”

When I was putting together the project album, I chose the poem “Zhugan” from the classic anthology “Book of Songs” to use in the introduction. Written over 2,000 years ago, “Zhugan” narrates the homesickness of a woman from the ancient kingdom of Wei, who had left home after marrying.

By the end of the project, I still hadn’t found the answer or the antidote to homesickness. But the women I had spoken with helped me understand the ways these emotions connected and stretched across space and time. They also gave me a female perspective on understanding family.

Later, Ah Liu launched an account on the Chinese social media app WeChat, where she shared the 107 family letters I had digitized for her. Through the account, she breathed new life into the story of her relationship with her father, and she now plans to publish a collection of those letters.

As for Lan Lan, she messaged me on WeChat recently to tell me she now wants to go back to China once a year.

“Even if it’s just for a few days, I’d have no regrets,” she said. “Exploring the world helps us grow wiser. Crying over homesickness will change nothing.”

Translator: Katherine Tse; editors: Dominic Morgan and Ding Yining.

(Header image: Letters from Ah Liu’s father on display in London, 2016. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone)