For Love or Money: What Drives China’s Migrant Mistresses?

This article is the second in a two-part series on Chinese “ernai.” The first can be found here.

I first met Ah-Fang in 2006. (To protect the anonymity of my interview subjects, I’ve chosen to give them all pseudonyms). By that time, the then-26-year-old migrant from a small village in the relatively impoverished southwestern province of Guizhou had been living in the southern megacity of Guangzhou for roughly seven years. Her boyfriend of two years, Ah-Jian, was a 40-year-old small-time businessman from southern Chaozhou City, and he had a wife and three kids.

“I don’t know why I’m with him; he’s not rich or influential,” Ah-Fang told me, adding that she wasn’t truly in love with him. Ah-Jian wasn’t particularly wealthy, and Ah-Fang still spent three or four days a week at a mahjong parlor-cum-garment workshop, alternating between playing mahjong and doing the odd bit of needlework. While the other women at the mahjong parlor gossiped about their neighbors, Ah-Fang seldom uttered so much as a word.

That year, roughly 36% of the country’s 131 million rural-to-urban migrants were women, a percentage that has largely stayed steady, even as the migrant population has risen to almost 300 million. Some of them, like Ah-Fang, reject the exhausting life of a migrant worker and instead enter into long-term relationships with married men, becoming what is known in China as ernai, a colloquial term for a woman involved in a financially dependent relationship with a married man. Some migrant women see these relationships as a way to move up the social ladder, while others simply see them as a way to survive the social displacement and emotional dislocation involved in the rural-urban transition.

Studies have shown that many female migrants experience feelings of loneliness, anxiety, insecurity, and exhaustion in their new lives. Before she became Ah-Jian’s ernai, Ah-Fang had lived in Guangzhou for five years. Her father died when she was 10, and she started working after dropping out of middle school at 14.

Arriving in Guangzhou at the age of 19, she spent her first few years there hopping from job to job, working at a garment factory, a shoe factory, and a toy factory. She never made it off the assembly line, however, leaving her stuck working 10-hour days for meager wages. Finally, her then-boyfriend was sentenced to jail for theft, and Ah-Fang decided she was burned out from the boredom and loneliness of the migrant lifestyle.

Not long after, she was arrested for overstaying her temporary residence permit — a document designed to allow urban authorities to maintain control over migrant populations. Ah-Jian, whom she’d been introduced to by friends two months prior, bailed her out. He took her back to his Guangzhou pied-à-terre — where he stays while in the city on business — and offered to make her his ernai. Scared and desperate, Ah-Fang agreed.

One reason migrant women like Ah-Fang enter into ernai relationships is their lack of support networks. Their distant families are unable to provide effective emotional care and support in times of need and crisis, and, in some cases, lack an awareness of the kinds of issues rural women face in China’s cities. Others migrate to the city in large part to escape their patriarchal families.

Either way, migrant women are often highly dependent on their friends and colleagues in their new homes. But it can be hard to forge these connections — especially with other migrants, a demographic characterized by high mobility and low social status.

Thus, more often than not, migrant women have no one they can depend on for help resolving their emotional problems. This influences the character of their ernai relationships. For instance, in my research I’ve found that the emotional bonds between migrant ernai and their partners tend to be stronger than those involving ernai who were born and raised in Guangzhou.

In addition, while it’s not uncommon for men — especially wealthy men — to abuse their migrant mistresses, many of the migrant women I interviewed consent to the arrangement precisely because their partners treat them humanely. For migrant women, kindness and emotional care are important. Just as ernai help men reclaim or perform their masculinity, their partners help ernai reclaim a sense of dignity, a feeling of being more than second-class citizens.

Meanwhile — unlike the local women I interviewed, who generally placed greater value on a man’s ability to materially provide for them — Ah-Fang’s concerns were less materialistic. Her boyfriend, Ah-Jian, was not particularly wealthy, but he made a decent-enough living selling cheap accessories produced in his hometown to flea markets and vendors in wealthier cities to both support his family and second wife.

“He’s a nice guy, very kind,” Ah-Fang told me. “I was also really bored and tired of working in the factory and had no hope for love anymore.”

Like Ah-Fang, many migrant women perceive their mistress roles as a temporary shelter from the drudgery of migrant life. Life on the factory floor is demanding, dreary, and often demeaning, and the factory-provided dormitories are typically cramped and poorly ventilated. As migrants, they are constantly subject to discrimination and harassment by locals and the police, which reinforces their second-class status.

Long-term intimate relationships, even with married men, offer them a reprieve. The homes their partners provide them offer a physical space they can call their own, one in which they can feel at home. And the material and financial support they receive frees them from the physical toll of working menial jobs and gives them a chance to have fun.

But while these relatively stable extramarital relationships offer migrant women a temporary shield, the attendant social stigma often ends up further isolating them from potential support networks, whether at work or in their neighborhoods.

After leaving her job and beginning her relationship with Ah-Jian, Ah-Fang cut herself off from almost all her friends. Many migrant ernai not only voluntarily cut ties with anyone who might tip off their families — especially other migrants from the same part of the country as them — but also keep a distance from their neighbors, who might judge them.

When I interviewed her, Ah-Fang had no plan for what came next, though she knew her relationship with Ah-Jian wouldn’t last forever. Ah-Jian informed her early on in their relationship that he would not divorce his wife. And although she felt close to him, Ah-Fang did not regard Ah-Jian as husband material, in part because of his personality. (Like many migrant women, she had absorbed the middle-class values of urban China and craved a partner with good communication skills and a sense of romance).

Yet Ah-Fang wasn’t overly concerned with her lack of prospects. Ernai relationships sometimes function as an excuse for postponing marriage, which many migrant women view as undesirable. Migration often leaves women struggling to balance their new ideals of romantic love and autonomy with the reality that they’ll eventually have to return home and marry someone from their hometown — and once again subject themselves to patriarchal rural family structures.

The structural and cultural barriers to achieving their romantic aspirations adds another layer of emotional distress to migrant women’s lives. In some ways, it encourages them to acquiesce to mistress roles, including ernai relationships.

Ultimately, Ah-Fang decided to focus on the present. “Thinking about the future only makes me anxious, upset, and desperate,” she told me. “It’s pointless to think about the future. Life is like that. No one knows what’s going to happen tomorrow.”

Editors: Cai Yiwen and Kilian O’Donnell.

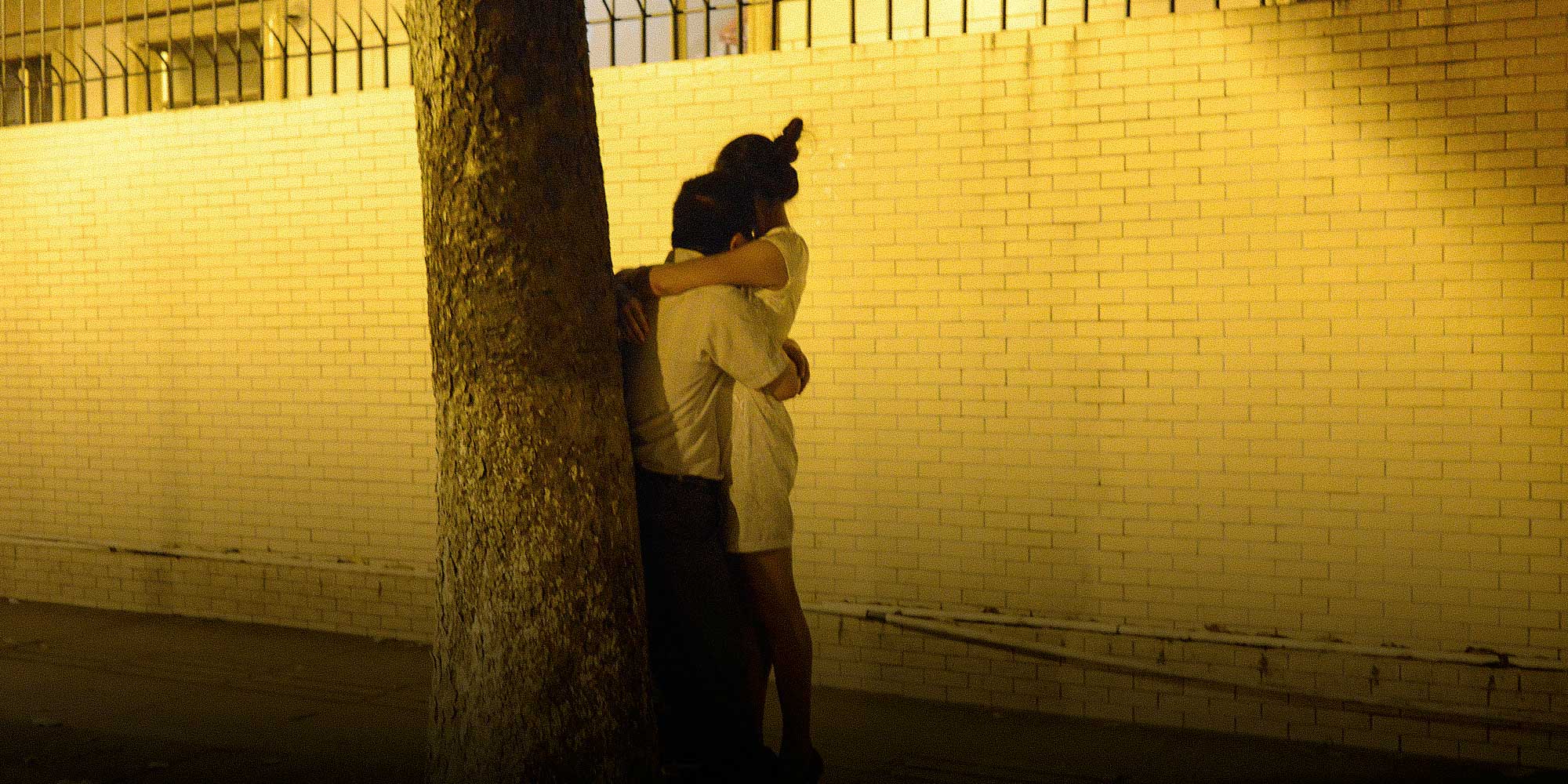

(Header image: Zhan Youbing/VCG)