Why Northeast China’s Forgotten Japanese Shrines Still Matter

This article is the third in a series on the South Manchuria Railway. The previous articles can be found here.

For more than 40 years, from the end of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 to the end of World War II in 1945, Japan dominated much and then all of northeastern China. Today, a great deal of evidence from Japanese colonial rule has been obliterated, but some traces can still be found — if you know where to look.

A century ago, imperial Japanese officials saw Northeast China, which they would eventually govern through the puppet state of Manchukuo, as a land of opportunity and fertile ground for their late-blooming colonial ambitions. Railroads, factories, and farms quickly sprouted up after 1905, along with a network of army bases to enforce their rule.

By 1945, there were more than 1.4 million Japanese living in the region — hundreds of thousands of them settlers — and they brought their culture and religions with them. The Japanese authorities recognized that the land’s spiritual colonization was just as important as its economic and industrial colonization, and they built Buddhist temples and Shinto religious shrines all across their new territory. The Chinese destroyed most of these structures after WWII, when they were seen as cruel symbols of the Japanese occupation, but a few of them still survive. Today, their remains pose a question: When and how should history be preserved?

I’ve spent parts of the past few years traveling through Northeast China along the Russian-built, Japanese-expanded Chinese Eastern Railway. In that time, I’ve come across a number of these colonial relics, from the port city of Dalian in the south to the former Manchukuoan imperial capital of Changchun, then known as Hsinking.

Changchun may be the easiest place to start for those interested in the Japanese colonial occupation. It was there that Puyi, the last emperor of China, resided until his puppet kingdom’s collapse in 1945. At the southeast corner of the former palace lie the ruins of the Manchukuo imperial family’s private shrine, the Kenkoku Jinja, which was built in honor of Amaterasu, the sun goddess in the Shinto religion. Destroyed by the Japanese as they evacuated the city, all that remains of the Kenkoku Jinja today is its stone foundation.

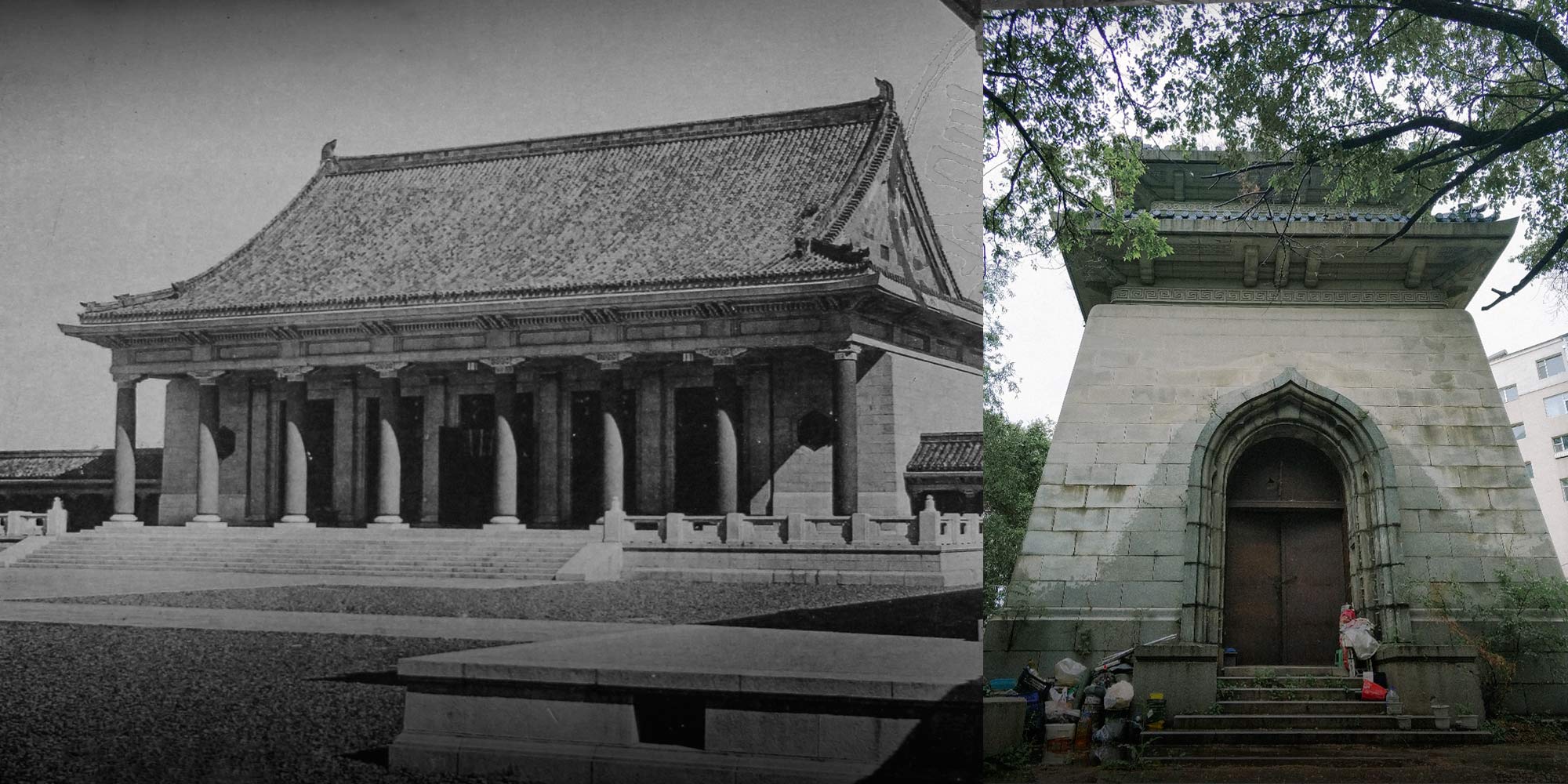

The Kenkoku Jinja was located within the imperial palace itself and was not open to ordinary citizens. A sessha, or auxiliary shrine, was therefore built in downtown Changchun, so that common people could pay their respects to Amaterasu. Called Kenkoku Chūreibyō — “Shrine to the Loyal Spirits of the Foundation” — it was completed late in the Manchukuo period. Today the shrine’s square pagoda is surrounded by vegetable gardens, and few nearby residents seem interested in its fate. “That’s the Yasukuni Shrine of Manchukuo,” one of the women tending their gardens told me, consciously linking the building to the controversial Japanese shrine for that country’s fallen soldiers.

Walking around the building, I came to the arched iron gate that dominates the temple’s front entrance, sealing it off from the street. It was locked, however, and while there was an exquisite ceiling relief in one of the temple’s turrets, I couldn’t get inside to see it.

Hoping to find a better-preserved example of Japanese religious architecture in Changchun, I asked a local friend of mine, who pointed me to Kongōji, a 102-year-old temple built in honor of the Shingon Buddhist sect, which originated on Mount Koya, south of Osaka.

But few people today treat it like a sacred space. Located at the end of an alleyway, its only link to the outside world is a narrow, dark passageway lined with tin sheds. When I visited, I found the temple surrounded by mountains of garbage. Only by climbing the stairs in an adjacent apartment building was I finally able to get a good view of the entire complex.

The main structure still looks more or less the same as it does in an old photo I found, but some of the walls, windows, and entrances are different, suggesting that it has since undergone a few renovations. A large, round pattern on the roof that I saw in the old photo was also nowhere to be found.

Such renovations were by no means unusual in the rare cases when Japanese colonial structures weren’t simply knocked down. In Dalian, the Japanese-built Shōtoku Hall, completed in 1911, was repurposed into a summer pavilion, and the statue of Prince Shōtoku — a semilegendary figure from the sixth century — was knocked down and replaced by one of Sun Yat-sen, the founder of modern China. More often they were just demolished. Demolition crews especially targeted Shinto shrines, as they were too reminiscent of Japanese rule, and most of the buildings that remain were either Buddhist or built in a vaguely Chinese architectural style.

The religious-building drive in Changchun was part of a broader Japanese effort to propagate the myth of Japan’s benevolent stewardship of the region, even as it sought to consolidate its hold on the land. In 1940, the Manchukuoan puppet emperor Puyi returned from a visit to Japan and declared Shinto the official state religion. The state required residents to study Japanese, worship Japanese deities, celebrate Japanese holidays, and take Japanese-style names.

Needless to say, by the time the region’s Japanese rule collapsed, people didn’t take too kindly to these structures, and there was little interest in preserving them. Even today, as a Chinese citizen, the religious edifices left by the Japanese evoke a complicated legacy. They’re symbols of China’s humiliation and of the attempted spiritual colonization of the local population. But, at the same time, I know they’re an important part of our past, and should not be lightly cast aside.

In 1945, few wanted anything to do with the legacy of Japanese imperialism, and their relics were left to rot. Now that enough time has passed to recognize their historical value, it’s too late. There’s a lesson in there, if we’re willing to see it: The dark side of history is worth remembering, no matter how traumatic it may be.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: Left: An exterior view of Kenkoku Chūreibyō, taken from an interwar-era postcard. IC; right: A view of Kenkoku Chūreibyō today, Changchun, Jilin province, May 28, 2018. Courtesy of Ma Te)