One Retiree’s Solution for Solitude: Nude Modeling

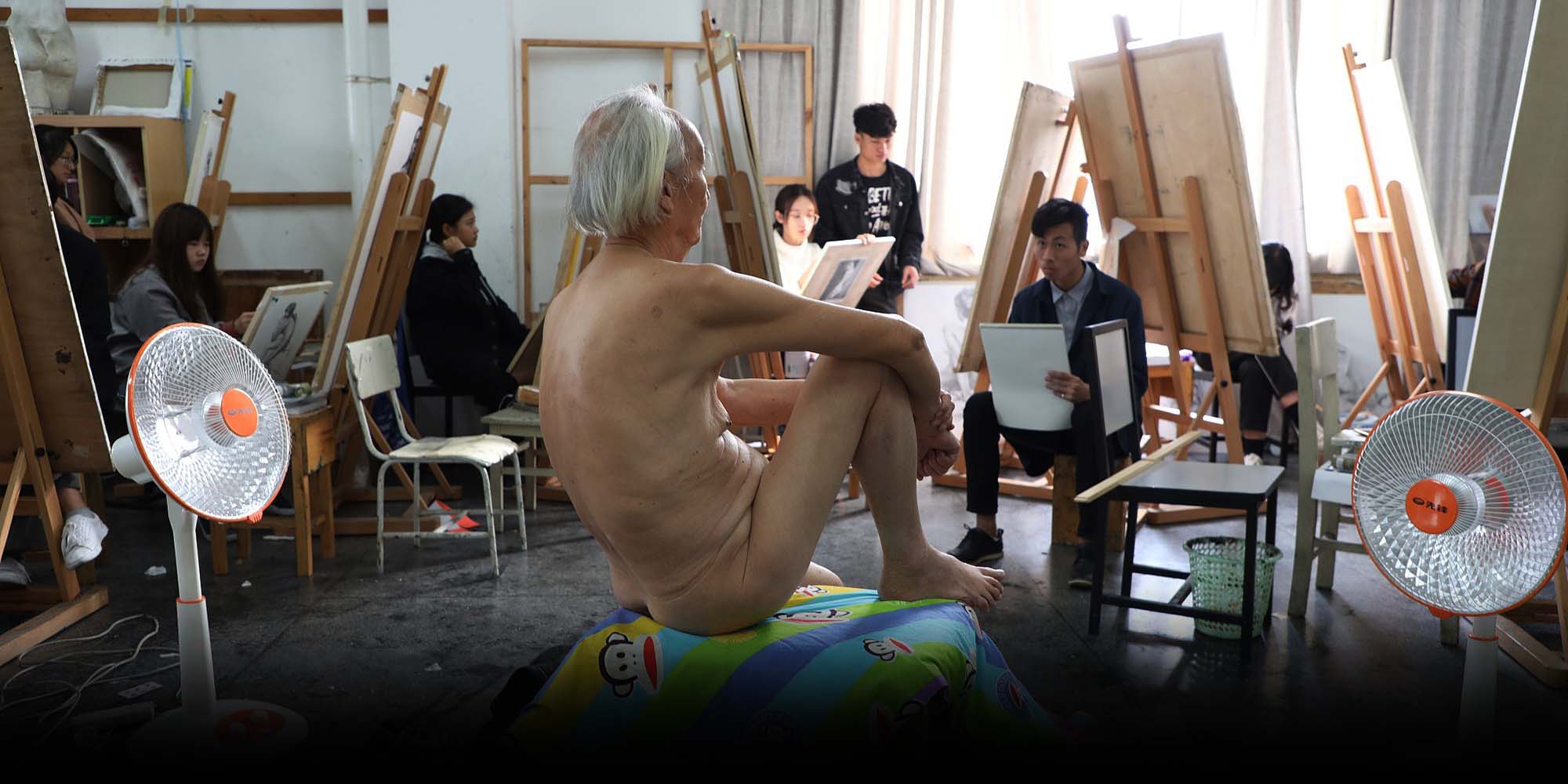

SICHUAN, Southwest China — As a nude model, Wang Suzhong cares about his appearance. Though he now stands at 1.68 meters tall, he stresses that he used to be a better-sounding 1.70: “I’ve shrunk by 2 centimeters.” When he bothers to brush his silver hair, it flows like that of a much younger man. In the past six years, he has modeled several times a week in nearly all the art institutes and colleges in town. For an 89-year-old, he has quite the career.

This unusual line of work is Wang’s answer to what has become known in China as the empty-nester problem, or when elderly people don’t live with their children. Until fairly recently, this was a rare situation in the country, but as younger generations prefer having their own homes, a majority of seniors now live alone. Empty nesters make up more than 70 percent of the elderly population in urban areas like Sichuan’s capital, Chengdu, a city of 14 million where one in every five is aged 60 or above. To make sure these lonesome seniors get enough attention, the filial duty to visit or call one’s parents became a law in 2013.

“I want to set an example for empty nesters like me, to find their own passion, be independent, and not become a burden on society,” says Wang as he takes a sip of the noodle soup he made for lunch — a lighter dish than normal, on account of a toothache. All Wang’s friends feel old and have health problems; some have passed away. But Wang’s new passion keeps him young, he says.

In 2012, when Wang was strolling past Sichuan Normal University near his home, he glimpsed a nude model posing for students at a life-drawing class at an art studio. Having worked as a tailor in the fashion industry all his life, Wang has always been fond of art involving the human form. When the manager of a figure-model agency noticed him, he looked Wang up and down a few times, and after a short pause asked if Wang wanted to be a nude model as well. “I thought about it for a day, and I was so excited that I tossed and turned in bed that night,” Wang says.

Wang wasn’t the least bit nervous the first time he modeled. In each class, he must maintain the same posture for an hour. Sometimes, he sits on a chair or sofa; other times, he stands or leans against the wall. “The students look so serious when drawing me, which makes me feel like I’m a work of art,” Wang says, flashing an easy smile.

When Sixth Tone meets Wang at his apartment in Chengdu, he’s on his day off. He’s wearing a dark jacket over a white shirt, and brown nylon pants. While eating his lunch, he watches international news on his new 55-inch TV; on a nearby desk is an assortment of fruit, a mirror, and a calendar themed after Chinese President Xi Jinping. His favorite portrait of himself hangs on the wall next to his bed. A student painted him sitting down on a table with his knees drawn to his chest and hands on his shins while looking into the distance. Wang says his mind is blank when he models for the students: “I don’t think about the past or the future. I just want to live in the moment.”

The public housing apartment costs 400 yuan ($58) in rent, just a tenth of his relatively generous monthly pension. He earns 110 yuan a day modeling, which he does up to three times a week. Wang doesn’t need the extra income. “Obviously, I’m not modeling for money,” he says. “When I’m working with the students, I feel like I’m not alone, and I’m still needed.” When Wang was younger, his mother needed him, then his wife needed him, and his children needed him. Now, his mother, wife, and younger son have passed away. The remaining three children have their own lives and rarely come to visit.

During summer and winter school breaks, when Wang’s modeling skills are not in high demand, he gets up at 6 a.m., reads his newspaper, and then buys food at the market. After cooking for himself, he goes to the neighborhood’s elderly service center and chats with other empty nesters. Despite being a big mahjong fan, Wang hasn’t played in a while. “I only enjoy playing with people I really like, but unfortunately they’ve all died,” he says. Sometimes, he joins the chorus at the park, singing revolutionary songs with other seniors.

Born in a small provincial city in 1929, Wang has gone through many of China’s most turbulent times, from World War II to the civil war that followed, and later the Great Chinese Famine and the Cultural Revolution. His father died when he was 3, and in 1942 Wang dropped out of school because his mother could no longer afford tuition. Wanting to fight the Japanese, he signed up for the air force, but an eye condition kept him from joining the war.

Wang then traveled to Chengdu to learn how to sew clothes from a relative. By 1949, when the People’s Republic of China was established, Wang had become a skillful tailor specializing in Western suits. He eventually became the general manager of a state-owned garment factory. He has taught more than 100 apprentices and has traveled all over the country, from cosmopolitan Shanghai to dusty inland cities, to meet with clients.

Wang’s career brought him abundant income. He was able to purchase three apartments in central Chengdu that he gave to his children, hoping that he could live with them in old age. However, after his wife died in 1997, his relationship with his children wasn’t particularly good. And it got worse when they found out about his modeling, which they consider “disgraceful,” Wang says.

Wang’s elder son works as a security guard. When he found out that his father would habitually strip naked in front of art students, he called and yelled that he wanted to end their relationship as father and son. Both of Wang’s daughters are retired. One visits him once every few months, and he has lost contact with the other. Wang’s family members declined Sixth Tone’s interview requests. Earlier this year, one of his granddaughters, a university student, told Sixth Tone’s sister publication The Paper that she’s happy her grandfather found his own passion.

“It’s not shameful to be a nude model at all,” Wang says. It’s the kind of art he learned briefly at school — Western-style life drawing and oil painting — but back then, he didn’t have the opportunity to study it further. Wang used to envy his fellow seniors who had their children and grandchildren for company, but now he’s relieved. “How long do you think I can live?” he asks. “I just want to follow my dream and make a contribution to society by doing something most people are reluctant to do.”

And there are plenty of people who do appreciate Wang. In China, he is something of a web celebrity, or wanghong — a term he has heard of, despite not owning a computer or smartphone. Several news stories about Wang have appeared in the past few years, and eye-catching headlines about the mysterious 89-year-old nude model have made him somewhat famous on social media. He is said to be the oldest such model in Chengdu.

Many of Wang’s neighbors know about his modeling and see him as an open-minded hippie. Zhang Guoxing, another retiree who lives in Wang’s complex, is aware of his neighbor’s nude modeling, though the two have never talked to each other. “I think many seniors in the community activity center have seen him on TV or on their phones,” Zhang says while walking his dogs. “What he does is great, pursuing his dream and fulfilling his life, but I would never have the guts to [be a nude model].”

As his reputation grew, Wang was invited in 2013 to star in a 45-minute movie titled “Free-Renting.” The film is an adaptation of a news story about an empty nester in his 70s who, in search of companionship, houses young people for free. Wang says he was basically playing himself. There is a line in the movie that describes his situation: “My wife is gone, children don’t come to visit, and I have made my own burial clothes.”

People of Wang’s generation expect their children to take care of them and bury them after they die. “I was so afraid to die without my children, but now I’m over it,” he says. “I will enjoy my remaining days and keep modeling until the day I can’t move.”

Editor: Kevin Schoenmakers.

(Header image: Art students draw Wang Suzhong in a studio at Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan province, Nov. 14, 2017. Wu Xiaochuan/VCG)