Patriot Games: How Nationalism Is Holding Chinese Athletes Back

This year’s Suzhou Taihu Marathon went viral for all the wrong reasons. As competitors He Yinli of China and Ayantu Abera Demissie of Ethiopia raced neck and neck toward the finish line during the women’s running event, two volunteers separately rushed onto the track to hand He Chinese flags.

The first attempted handoff was unsuccessful, but the second volunteer managed to stuff a flag into He’s arms. The Chinese runner continued for a few steps before casting it aside in an apparent effort to keep pace. It’s not obvious who would have won had the volunteers not intervened — the second flag-bearer appeared to temporarily disrupt Demissie as well — but the interference undoubtedly cost He valuable time in a race she ultimately lost by only five seconds.

What is clear is that the volunteers’ actions were entirely inappropriate and put He in an awkward position. A national flag may not be heavy, but it’s ridiculous to expect an exhausted runner in the midst of a heated duel for the winner’s laurel to carry what is essentially a sodden parachute. There’s a good reason that athletes have traditionally waited until after the competition to drape themselves in their country’s colors.

But this hasn’t stopped Chinese patriots from criticizing the runner for what they saw as a lack of national pride. The blogger and marathoner Wei Jing called out He on the social platform Weibo, asking, “Is victory really more important than the national flag?” Forced to respond to a torrent of online criticism, a beleaguered He defended her actions, writing, “I didn’t throw the flag away, it was soaking wet and my arms were stiff.” Nevertheless, He concluded her post with, “I’m very sorry, and I hope you can understand.”

Fortunately, at least some commentators seem to recognize that He Yinli is not the one who should be apologizing. Shortly after the race, state broadcaster CCTV published an editorial on its website lambasting He’s detractors and the “moral blackmail” that forces athletes to choose between victory and patriotism. Striving to do well is patriotic in itself, the author argued, and all this latest incident had done was expose the immaturity of marathon organizers and other critics online.

It is the people behind the stunt who should be apologizing, not He. It’s unthinkable that in 2018 there are still those who fail to understand the basic etiquette of allowing a competition to conclude before carrying out nationalistic displays.

Yet in an anonymous interview with Beijing Youth Daily the day after the marathon, one of the event’s organizers continued to defend the handoff, at least in principle. This year’s Suzhou Taihu Marathon was part of the Running China marathon series put on by CCTV and the Chinese Athletic Association, and competition rules state that Chinese runners within 200 meters of the finish line should be given a Chinese flag to carry. “It’s a good look to have the national flag draped over your back,” the anonymous individual was quoted as saying, pointing out that this was the first such mishap that organizers had experienced in more than 20 races. Still, the interviewed organizer admitted that the particulars of the day’s race made the handoff a mistake: “We have been trying to contact He Yinli, and we sincerely apologize.”

As its flag policy suggests, the Running China series — like so many sporting events around the world these days — is as much about patriotism as it is athletics. Sports have long been used to arouse nationalist sentiment — especially when competitors from different countries go head-to-head — so it’s no surprise that politicians would invest so heavily in promoting their motherlands’ sporting programs, or that they would seek to blur the lines between sporting and national success for their own gain. You have only to look at the Olympic Games to see this in action. The Suzhou leg of the Running China series was actually being used to promote the Belt and Road Initiative — China’s trillion-dollar global infrastructure and trade project — so it’s ironic that organizers’ obsession with performative nationalism might have cost a Chinese runner the race.

Indeed, it’s often athletes who pay the price when things go wrong. This is especially true in China, where sports media organs often conflate athletic and national success. Meanwhile, a state-run training program provides generous funding and valuable coaching to young athletes while also controlling their training regimens and public appearances. If you win, you are held up as a paragon of the system at work; fail, and you risk being reviled as a traitor to the Chinese people and nation.

Liu Xiang, China’s most famous hurdler, knows this better than most. Liu became a national hero when he tied the world record in the 110-meter hurdles at the 2004 Olympic Games, a feat that led Chinese media to dub him “Asia’s Flying Man.” Four years later, after an injury forced him to pull out of a race at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, netizens gave him a new nickname: “China’s national shame.”

Liu’s fall from grace is far from unique in the annals of Chinese sporting history. Before Liu, it was Li Ning who bore the brunt of his country’s reprobation. A famed gymnast, Li was vilified after making a series of mistakes during an event at the 1988 Seoul Olympics. One disgruntled fan even sent him a noose, along with a note telling Li to hang himself. And when Lang Ping, a respected volleyball coach and former star of the Chinese national team, led the American women’s volleyball team to victory over China in the Beijing Olympics two decades later, she was disparaged online as “traitorous scum.”

One of the few athletes to escape this cycle is the tennis player Li Na. Li has shied away from associating herself with the Chinese sporting system and from being used as a political symbol. An outsider of sorts, Li is known for her atypical frankness on the subject of sports and patriotism. “I am only a tennis player,” she once said. “I don’t play for my country, but to do my job well.”

While her attitude was originally the subject of heavy criticism — especially after failing to thank China when she won the Australian Open in 2014 or the French Open in 2011 — the country’s tennis officials seem to have smartly realized that it doesn’t matter what she says: If she wins, they can take credit, and if she loses, it’s easy for them to shirk the blame.

Sports allow us to test ourselves against the very limits of human endurance — limits that the best athletes somehow find a way to transcend. Sadly, this latest fiasco is a reminder that the barriers erected by nationalism are less easily overcome. He Yinli set out that morning to win a race, not become a national symbol. Yet in the end, her country tried to turn her into one anyway, letting her down in the process. If China wants to compete on the global stage in the future, it could use a little less of the Suzhou Taihu Marathon’s nationalism and a little more of He’s sporting spirit.

Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Zhang Bo and Kilian O’Donnell.

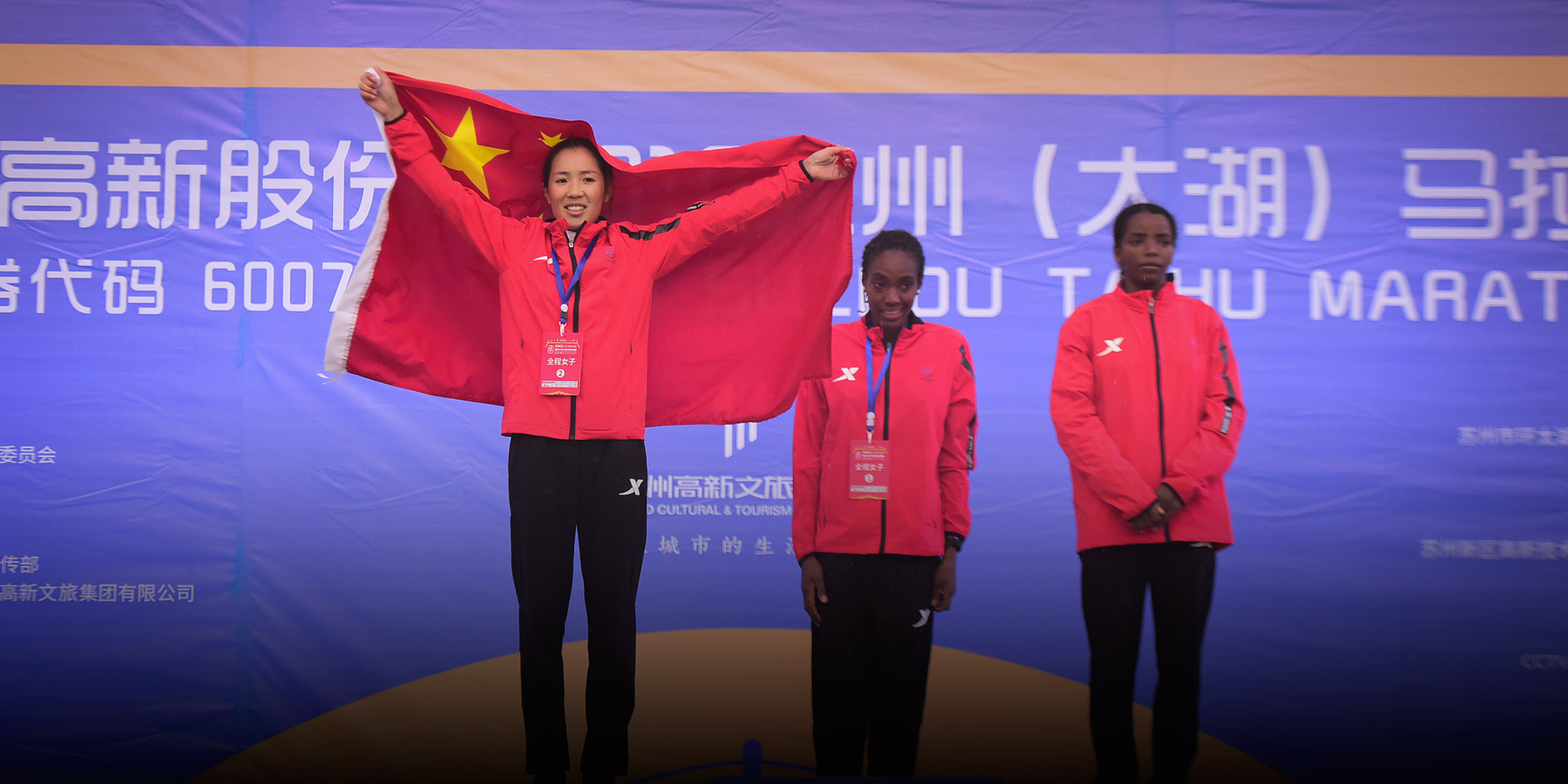

(Header image: He Yinli waves the Chinese flag after finishing second at the 2018 Suzhou Taihu Marathon in Suzhou, Jiangsu province, Nov. 18, 2018. Guan Yunan/VCG)