How The ‘Gaokao’ Rewards Students for Being Rich

Back in March, China’s Ministry of Education eliminated a number of preferential programs that allowed students to earn bonus points on the gaokao, China’s college entrance examination. Now, students are no longer eligible for extra marks based on standout performances in athletic, artistic, or scientific competitions. Bonus points for being granted the title of “provincial-level outstanding student” have also been abolished.

Programs bestowing bonus points on the gaokao date to the 1950s, when the policy was originally meant to benefit students from working-class and rural backgrounds. During the Cultural Revolution, the gaokao was suspended; after the central government revived it in 1977, it gave extra gaokao points to students from certain ethnic minority groups, as well as to those with consistently excellent grades, to student cadres, and to promising athletes and artists.

At its peak, the bonus point policy included more than 200 different programs. By 2015, at least 10 percent of all test-takers in the municipalities of Beijing and Chongqing, as well as in Hainan, Henan, and Hubei provinces, received bonus points on their gaokao.

However, the sheer number of ways to beef up your test scores provided fertile ground for corruption and cheating. In recent years, the policy has been dogged by scandal. In 2014, for example, reports surfaced of test-takers in the northeastern province of Liaoning and central province of Henan purchasing faked athletics certifications, thereby becoming eligible for bonus points on the gaokao. In the wake of the scandal, the bonus point system as a whole faced heavy criticism.

In China, gaokao scores carry profound repercussions for a student’s life chances. On a test where every point counts, 20 extra marks can mean the difference between going to a decent university and attending a mediocre one. But although bonus point programs have been criticized as unfair, until relatively recently, the country has failed to understand whom exactly they serve. With this question in mind, back in 2012 our research team carried out a sample survey at 22 higher education institutions in China. We found that a test-taker’s family background plays a significant role in determining whether or not they receive bonus points on the gaokao.

First, students from families who hold urban household registrations are far more likely to receive bonus points than those from the countryside. Among test-takers who received a score boost, more than 75 percent hailed from a city or town — even though urban residents comprised just 35 percent of China’s total population in 2012.

Second, those from higher socio-economic backgrounds are far more likely to be awarded bonus points than those on society’s lower rungs. Students whose parents are cadres in government or government-affiliated institutions, corporate managers, private entrepreneurs, or who have specialized scientific or technical knowledge made up 58 percent of bonus point recipients; meanwhile, the far more numerous children of low-level workers, farmers, and the unemployed or partially unemployed together account for less than 20 percent of the total.

Third, whether or not a student receives bonus points is also influenced by their father’s educational background. Among students who were awarded bonus points, 57 percent had a father who had received a post-secondary education.

It is clear that the bonus point policy has largely benefited the middle and upper classes, and that bonus points themselves have morphed into a form of class privilege. Science Olympiads and model plane competitions, each costing several hundred yuan to enter, are held to give the children of well-to-do families an opportunity to earn bonus points, while less well-off families lack the money and time to participate. Although bonus point programs hide behind the concept of a liberal, holistic education, they — and the elite university spots they lead to — disproportionately benefit children from privileged backgrounds.

The reality of bonus point programs is even more depressing when we consider that they started out as ways to assist members of underprivileged groups. The system was originally designed as a form of positive discrimination that would provide a path to a university education for the children of low-level workers and farmers. Today, however, bonus points give the affluent a leg up, depriving children from underprivileged backgrounds of educational opportunities. These programs run counter to the meritocratic ideals of the college entrance exam, exacerbate inequality of opportunity, and create feelings of injustice among the general public.

In recent years, the popular expression “Poor families rarely produce nobles” has surfaced repeatedly in Chinese media as the rich-poor divide in education has attracted public attention. Bonus point policies are not only incapable of reducing educational inequality — they actively contribute to it. Almost every nation has adopted targeted measures to try and ensure equal access to education: Colleges in the United States, for example, frequently implement affirmative action policies to mitigate educational inequality that primarily manifests along racial lines. China, too, has programs targeting students from rural or impoverished backgrounds, but the bonus point system largely undermines all initiatives that aim to help poorer children achieve academically.

In 2013, I co-authored a report showing that student enrollment in higher education is split along socio-economic lines, too. Students from more affluent backgrounds are more likely to attend elite universities, while those from poorer families are more likely to attend lower-tier schools. As the former group is more likely to get bonus points on the gaokao, students from less affluent backgrounds are pushed out of China’s top universities, further exacerbating social stratification and segregation at the country’s higher education institutions.

On the whole, the bonus point system has put children from disadvantaged backgrounds in even more unfavorable positions. The 2003 decision allowing some universities to take charge of their own enrollment procedures already serves to provide a path to university for unique talents and elite students, and there’s no need to rely on bonus point programs to fill this role any longer.

Now is the right time to end bonus point programs in their entirety. At present, the only reason some programs still exist is because of inequality in China’s basic education system. Ethnic minorities and test-takers from poorer areas lack basic educational resources, and steps should be taken to get more of them into universities. But state-sanctioned bonus point programs — at least in their current form — show precious little appetite to do so.

Translator: Kilian O’Donnell; editors: Lu Hua and Matthew Walsh.

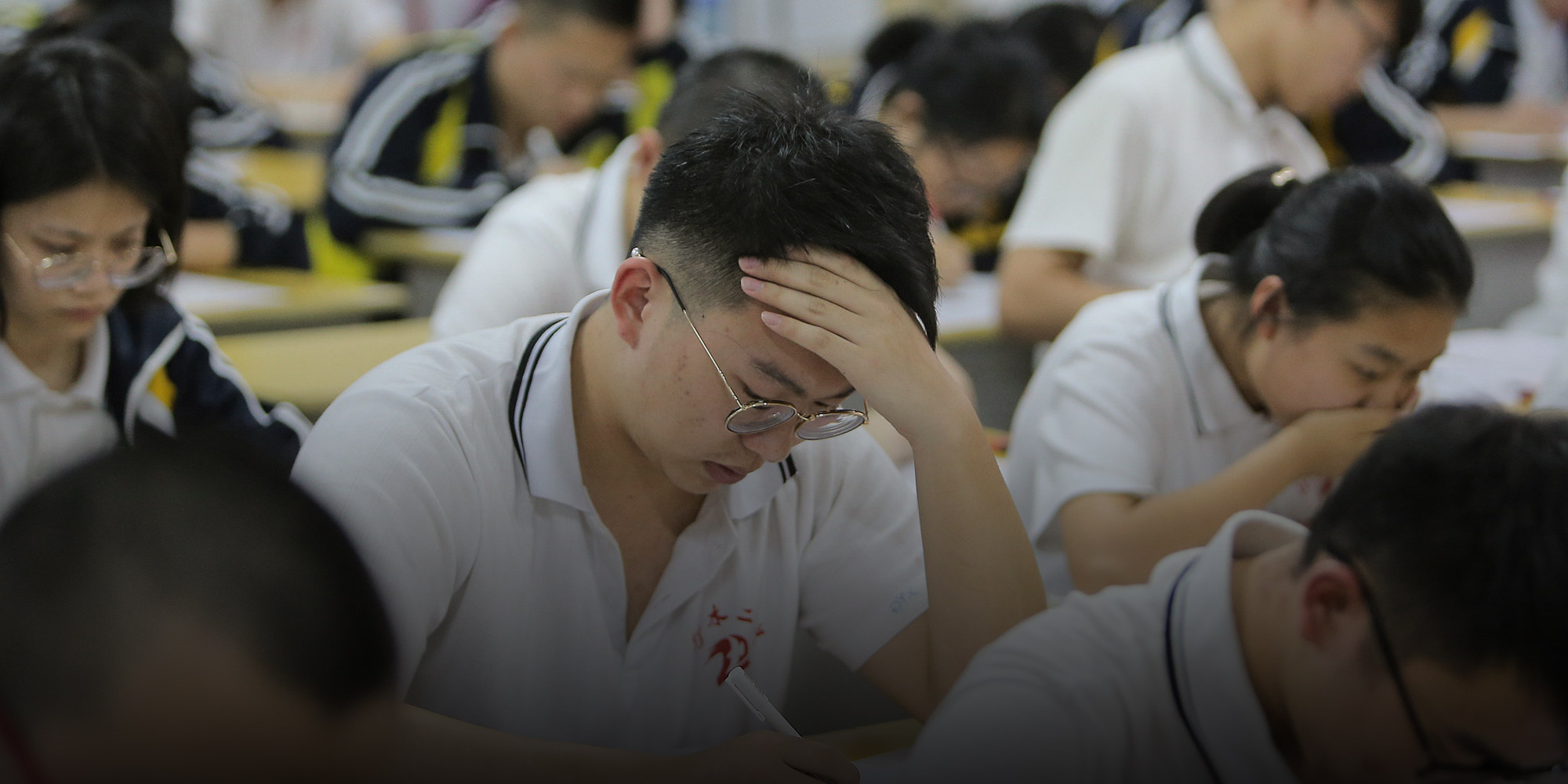

(Header image: Students take a test at a high school in Hengshui, Hebei province, May 3, 2018. Yan Nan/VCG)