How Chinese Police Interviews Fail Sexually Abused Kids

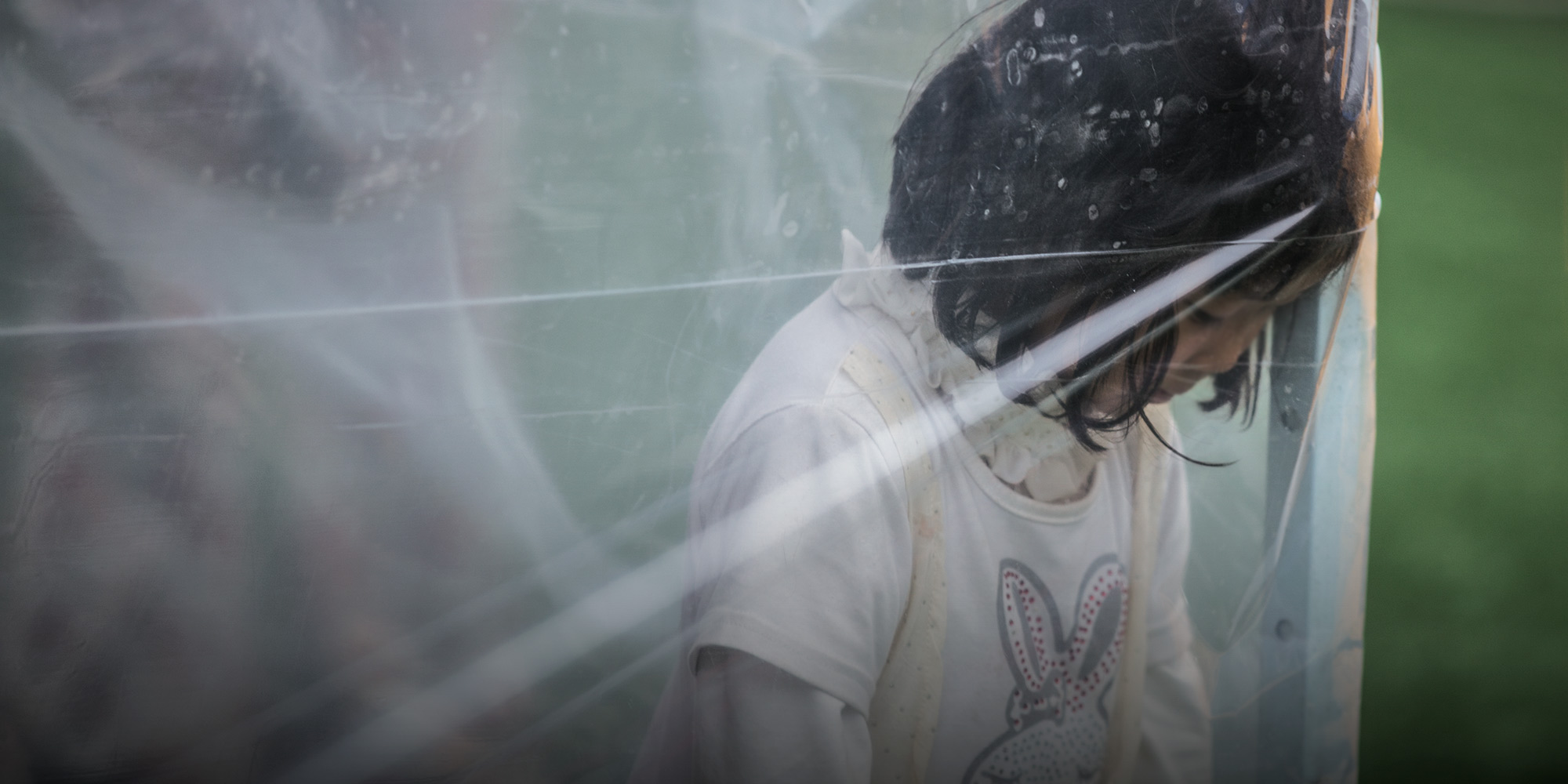

When 4-year-old Zhenzhen was taken to the police station for the third time, she bowed her head and said nothing when shown a photo of her alleged abuser. The little girl couldn’t understand why she had to answer the same questions over and over: What happened to you? When and where did it take place? Is this the man who molested you?

The issue of child sexual abuse is emerging from the shadows in China, spurred by a series of high-profile cases beginning around six years ago. Legal reform has made it easier to prosecute perpetrators, while awareness efforts have chipped away at longstanding stigmas around reporting sexual abuse for fear of bringing shame to the family.

But as the culture of silence begins to thaw, there are still significant gaps in law enforcement’s handling of the hundreds of children who come forward with sexual abuse allegations each year. In lieu of specialized interview procedures, police often treat child victims like adults, using questioning methods that can scare children and produce false accusations. What’s more, many police investigations don’t give child testimony much weight — but in a majority of cases, this is the only evidence.

According to data from Girls’ Protection, an NGO dedicated to preventing child sexual abuse, there were 1,151 reported cases of sexual assault of minors between 2015 and 2017. Many more likely go unreported due to persistent stigmas, particularly in rural areas — and most never see justice served, according to lawyer Lai Weinan.

“The fact that the vast majority of cases of sexual assault involving children can’t be cracked by the police is a big disappointment to families and discourages many from pursuing the cases and punishing the criminals,” says Lai, who works pro bono to help child victims of sexual abuse and represented Zhenzhen’s family two years ago.

If it weren’t for the pain she was feeling, Zhenzhen — a nickname used to protect her privacy — might never have told her mother that she had been inappropriately touched by a classmate’s uncle for as long as half a year. In 2016, the kindergartner often went to her classmate’s home after school in the southern city of Shenzhen. There, the other girl’s uncle would give his niece 5 yuan ($0.80) to buy snacks from the grocery store, leaving her alone with the man, Zhenzhen explained in sign language to her deaf mother.

“He closed the door, turned off the light, and pressed me against a desk, or sometimes onto the bed,” the 4-year-old told police. One day, the man touched her between the legs. That night, she told her mother during a shower that her crotch hurt.

“A 4-year-old couldn’t have fabricated so many details,” Lai tells Sixth Tone. “But the police told me they don’t value testimony from a child as highly as that from an adult.” The third time Zhenzhen was brought into the interrogation room to answer the same set of questions, she began to wonder whether she had erred. When shown a photo of the man she said had touched her, she went silent.

“I was livid at how the police dealt with this little girl,” says Lai. “I urged them to acquire all necessary information in one interview to minimize harm to the child. But they ignored me and continued interviewing the child the way they deal with adults.”

Police routinely ask adult witnesses the same questions over and over to verify information, but this method can confuse children. They may think their answers are wrong and either shut down or offer false information in an attempt to please the adults in the room. Instead, interviewing minors requires a specific set of tactics, says Pekka Santtila, a professor of legal psychology at New York University Shanghai.

“An interviewer should do a practice narrative — they can check what the kids did on their birthday. If you get a child to do such practice narratives, they’re likely to tell you many more details of the alleged abuse,” explains Santtila, who has years of experience working with police abroad on sexual abuse cases involving minors. “Ground rules should be made clear later: It’s OK to say, ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I don’t remember.’ And tell the children, ‘If I make a mistake, feel free to correct me.’”

Victim testimony is crucial in child molestation cases because 70 percent of the time, says Santtila, it’s the only evidence — as it’s often too late to collect physical proof, there may be no bodily injury, and so on.

But many investigations are dropped due to low confidence in children’s accounts. This was the case for Zhenzhen: The police eventually dismissed her allegations, citing lack of evidence. Discouraged, her family chose to drop the matter and leave the city. The police in Shenzhen’s Longgang District declined to comment when contacted by Sixth Tone.

In fact, “children are potentially as good witnesses as adults,” Santtila says. Numerous studies have shown that children and adolescents can give accounts of past events just as reliably as adults, with their accuracy rate often at 85 to 90 percent. Even kids as young as 4 can offer trustworthy testimony, says Santtila — it all depends on how they are questioned.

To aid in police training, Santtila has developed computer simulations based on studies of real children. “The avatars have either abuse memory or non-abuse memory. The interviewers can find it out by asking open questions — or if they use many leading or closed questions, they could find out inaccurate feedback from the avatar,” he explains. For example, if a child mentions during questioning that an adult touched them, responding with: “Tell me more about that” is preferable to asking: “Where did he touch you?” Santtila says his team is developing a Chinese version of the technology, which is currently used in countries where he has collaborated with local police, including his native Finland, Estonia, and Japan.

Whether led by humans or avatars, this sort of specialized training is unheard of at most Chinese police stations. In 2013, top legal authorities in the country issued an opinion stating that police handling child sexual abuse cases should prioritize protection of the minors, who are not yet physically or psychologically mature. The opinion — which has the force of law — is the closest thing China has to a national guideline on procuring victim testimony in cases of sexual assault against minors, an offense that has been in the criminal code since 1979.

Sexual violence against children has come to the fore in just the past few years. In one prominent case from 2013, a principal was accused of raping six primary school students in the southern island province of Hainan; that same year, a 12-year-old girl in central China’s Hunan province became pregnant as a result of sexual assault. Public attention to the issue has only grown since: Just last November, parent allegations of misconduct — including molestation — at a Beijing kindergarten shook the nation, even though the accusations were ultimately dismissed. Legal reform has followed, expanding the criminal code to protect teenage boys from sexual assault in 2015 and banning sex offenders from working with children in Shanghai last year.

Now, Beijing may be leading the charge for reform to police procedures: In 2012, the city’s Haidian District formed a team of 10 police officers to deal exclusively with cases involving minors, including sex crimes. But even here, there is no systematic child interview training for officers, says Li Han, vice director of the Beijing Chaoyue Adolescents Social Work Services Agency. Instead, police partner with Li’s organization in handling children across a range of cases.

Every year, the nonprofit social work agency meets with 10 to 15 child victims of sexual abuse whose families have agreed to pursue investigations. The social workers provide psychological support to such families and help put children at ease during police interviews. Li recalls one successful collaboration in which officers and social workers interviewed a 7-year-old girl at her home, using a doll to help her communicate her account of sexual abuse.

But many more cases don’t make it this far, according to Li, as parents decline help due to deeply rooted stigmas. “Families who accept our services are comparatively open-minded,” says Li. “For the families of extremely young victims, they normally choose not to talk about the issue with the kids, as they don’t know how to have such a conversation.” Other parents react too emotionally to allegations of abuse and bombard the child with leading rather than open-ended questions, says Li, which is also counterproductive.

Bringing in social workers to help police interview child victims could someday be a viable solution nationwide — but low pay and poor career prospects have resulted in a severe shortage of such personnel. China has pledged to build a force of 1.45 million social workers by 2020. Yet data from 2017 indicated there were only 760,000 social workers in the country, and the lack of professionals in fields like crime prevention and child services has yet to be properly addressed.

On the judicial side, Zheng Ziyin, a lawyer who specializes in child sexual abuse cases, says he has seen encouraging progress in courts’ treatment of child testimony.

Zheng cites a 2014 case that hinged on a 3-year-old girl’s account of sexual assault at the hands of a 65-year-old school security guard. Without physical evidence, police in the southern city of Guangzhou had previously dismissed the allegations — but a judge insisted that the girl’s testimony was worth considering, and the man was sentenced to 18 months in prison on appeal. “In my observation, legal officials are demonstrating more trust in children’s accounts,” Zheng tells Sixth Tone.

“In general, I’m optimistic that the judicial environment for cases of sexual assault against minors will keep improving, and at a growing pace,” adds Zheng. “But with the police force, I’m not so optimistic.”

Editor: Jessica Levine.

(Header image: Yang Yi/Sixth Tone)