Chinese Scientists Unlock Key to Anti-Malaria Drug

Chinese scientists have finally unraveled the genome of sweet wormwood, a shrub native to China that naturally produces an anti-malarial compound.

According to a study published Wednesday in Molecular Plant, a journal under Cell, the researchers were able to dramatically boost the production of artemisinin, a compound used to treat malaria. Across the world, the fatal disease takes one child’s life every two minutes.

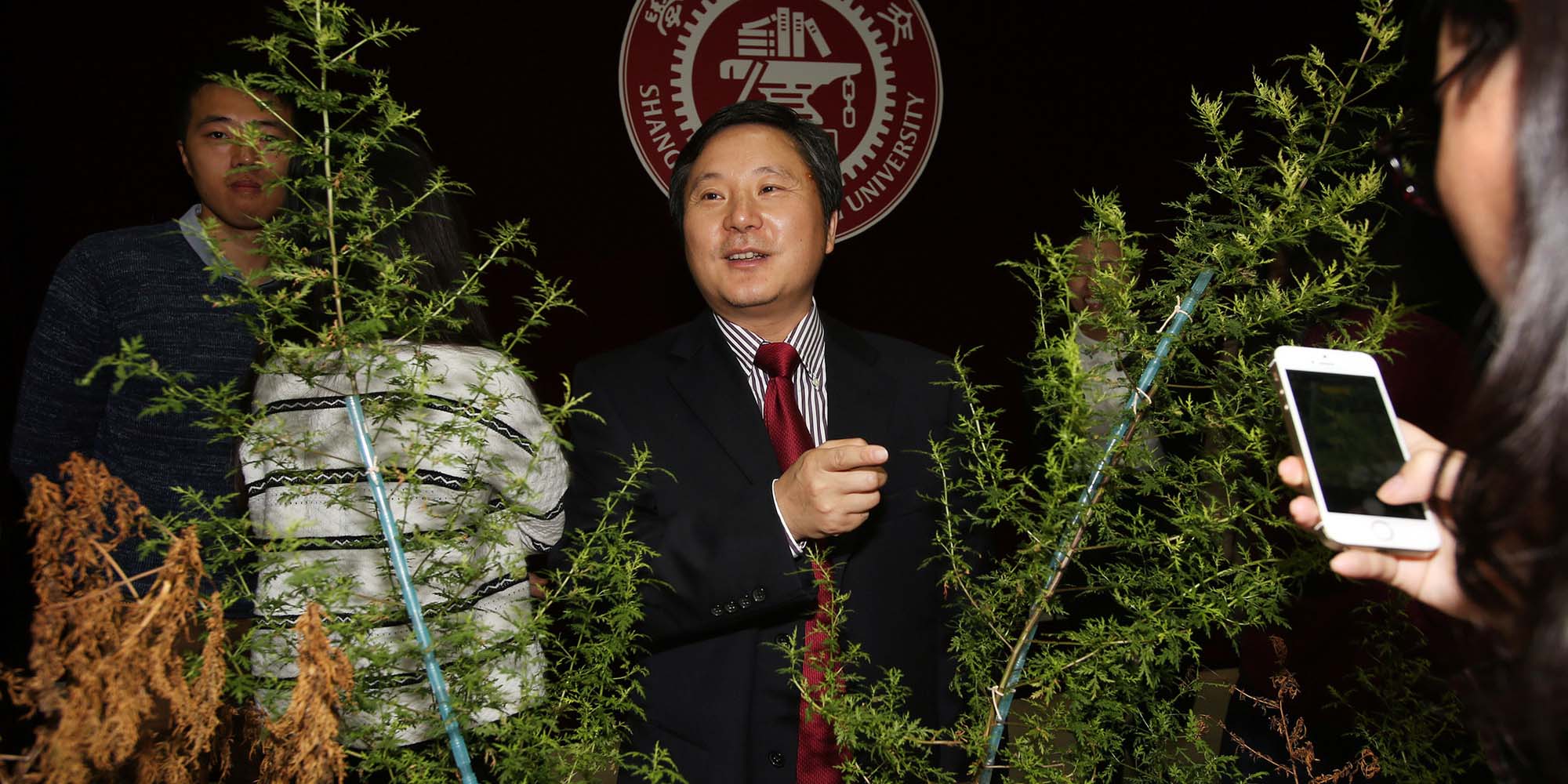

“Nearly half of the world’s population is at risk of malaria,” Tang Kexuan, a professor at Shanghai Jiao Tong University and a senior author of the study, said in a press release sent to Sixth Tone. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), malaria caused an estimated 445,000 deaths worldwide in 2016, when approximately 216 million people in 91 countries were affected — 5 million more than the previous year, and a worrying trend after years of decline.

Artemisinin was discovered in the early 1970s by Chinese scientist Tu Youyou and her colleagues. It has proved effective in killing the plasmodium parasites that cause malaria, and artemisinin-based therapies have been used as a first-line treatment for malaria for over a decade. Tu was awarded a Nobel Prize for her discovery in 2015.

However, the sweet wormwood plant produces very little artemisinin naturally — just 0.1 to 1 percent of the dry weight of its leaves. As such, global demand for the drug is not being met. Researchers have struggled for years to harness the compound’s therapeutic potential, but a lack of understanding of the sweet wormwood genome was a major impediment.

After five years of work, Tang and his colleagues were able to generate a complete sequence of the plant’s genome, containing over 63,000 protein-coding genes. Of these, they identified three genes related to artemisinin production. By activating these genes, they were able to achieve a threefold increase in production of the drug.

Seed samples of the genetically modified sweet wormwood have been sent to Africa for trials, and the scientists have set a goal of enhancing artemisinin production to 5 percent of dry leaf weight, up from the current 3.2 percent.

People with HIV, women who are pregnant, children under 5, and nonimmune migrants are especially vulnerable to malaria. Plasmodium parasites are transmitted through mosquito bites. When they enter the bloodstream, they invade liver and red blood cells, where they reproduce. Eventually, the infected cells burst, spreading more parasites throughout the bloodstream and causing high fever, chills, brain damage, and even death.

At present, around 90 percent of worldwide malaria cases and deaths occur in Africa. In 2015, the WHO set a goal of reducing malaria cases by 40 percent by 2020, but progress has stalled due to drug resistance and a lack of funding after an unprecedented few years of advances. Earlier this month, however, pharmaceutical giants GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis joined Microsoft founder Bill Gates and others to pledge nearly $4 billion toward anti-malaria research.

“In recent years, we have made major gains in the fight against malaria,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the WHO’s director-general, said in a November 2017 press release. “We are now at a turning point. Without urgent action, we risk going backwards, and missing the global malaria targets for 2020 and beyond.”

With the latest research progress, though, Tang believes that more affordable anti-malaria drugs are on the horizon. “If a plant can produce more artemisinin, it will be possible to reduce the price while still allowing pharmaceutical companies to profit,” the scientist told Sixth Tone. “Hopefully, many more people will be able to afford the drug in the future.”

China currently produces around 80 percent of the world’s artemisinin. While sweet wormwood typically grows in mountainous areas, Tang’s team has developed a new variety that can grow in grasslands and even alkaline soil.

“Our strategy for the large-scale production of artemisinin will meet the increasing demand for the medicinal compound and help address this global health problem,” Tang said. Having the full gene sequence of sweet wormwood can facilitate research on other compounds effective in treating malaria, Tang added, referring to substances that could potentially be used to treat artemisinin-resistant strains — a growing concern.

Apart from malaria, artemisinin is also believed to have applications for treating a wide variety of conditions such as tuberculosis, cancer, and diabetes. A new lupus drug containing the compound is now in clinical trials.

“Millions of people still cannot afford anti-malarial drugs at their current prices,” said Tang. “The demand for artemisinin is huge.”

Editor: David Paulk.

(Header image: Tang Kexun (middle) introduces his research outcomes on wormwood during a press conference in Shanghai, Oct. 27, 2015. IC)