More Nanjing Massacre Miscreants Detained by Police

A man was detained in eastern China on Saturday after posting “extremist speech” about the Nanjing Massacre in a private chat group, according to the official Weibo microblog account of the Nanjing police. The case is the latest in a series of investigations related to historical events.

On Thursday, the Nanjing Public Security Bureau posted a notice detailing two recent incidents. The first involved a 27-year-old man, Wang, who was working in Nanjing, capital of Jiangsu province, though he originally hailed from Jinan, capital of neighboring Shandong province. Posting under the name “Father Christmas” in a WeChat group of some 315 job-seekers, Wang is described by police as having “vented his frustrations” at the low salaries being offered in want ads.

“Nanjing is a pit,” Wang wrote. “We should let the Japanese come slaughter again.” Local police were alerted to the incident after screenshots of Wang’s messages were circulated on social media, and they arrested him two days later.

The same Weibo post from the Nanjing police referred to a second man who had encouraged users of QQ, another social messaging app, to take violent action against the authorities because of how they had handled — or in his view, mishandled — the case of a failed Nanjing-based investment platform called Qianbao.

Many of China’s most historically significant events — including the mass slaughter of Nanjing residents by the invading Japanese army in 1937 — must be treated with the utmost care. On Feb. 21, the Weibo account of the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall criticized two men who had donned Japanese military uniforms and posed for photos at Purple Mountain, the site of a major battle. Two days later, a 35-year-old man was detained in Shanghai after repeatedly insisting in WeChat messages that too few had died during the infamous massacre.

Businesses have also been known to hurt the feelings of the Chinese people because of a lack of historical sensitivity. In August 2017, a Shanghai company was booted offline for two months after it produced a social media sticker set featuring the real-life “comfort women” whom Japanese soldiers had used as sex slaves during World War II. And in December, a salad restaurant near the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall was ordered to cover its sign after netizens complained that the diner’s name sounded too similar to the Chinese term for the somber historical event.

Works of art such as songs and poems can prove sensitive, too — especially those describing wartime events. In January, a parody of a famous revolutionary ballad that instead celebrated year-end bonuses was derided as “blasphemous” by Party newspaper People’s Daily. And earlier this month, a deputy to the National People’s Congress suggested that companies and individuals responsible for such irreverent reproductions of venerated cultural classics should be severely punished.

In September 2016, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, China’s state prosecutor, introduced internet regulations stipulating that an individual’s digital data — including text messages, images, emails, and blog posts — can be used as evidence in a court of law. The following year, new rules were passed making the “owners” of WeChat groups legally responsible for content posted by other members, whose complete chat logs would also be stored for potential police use for a period of at least six months.

Editor: David Paulk.

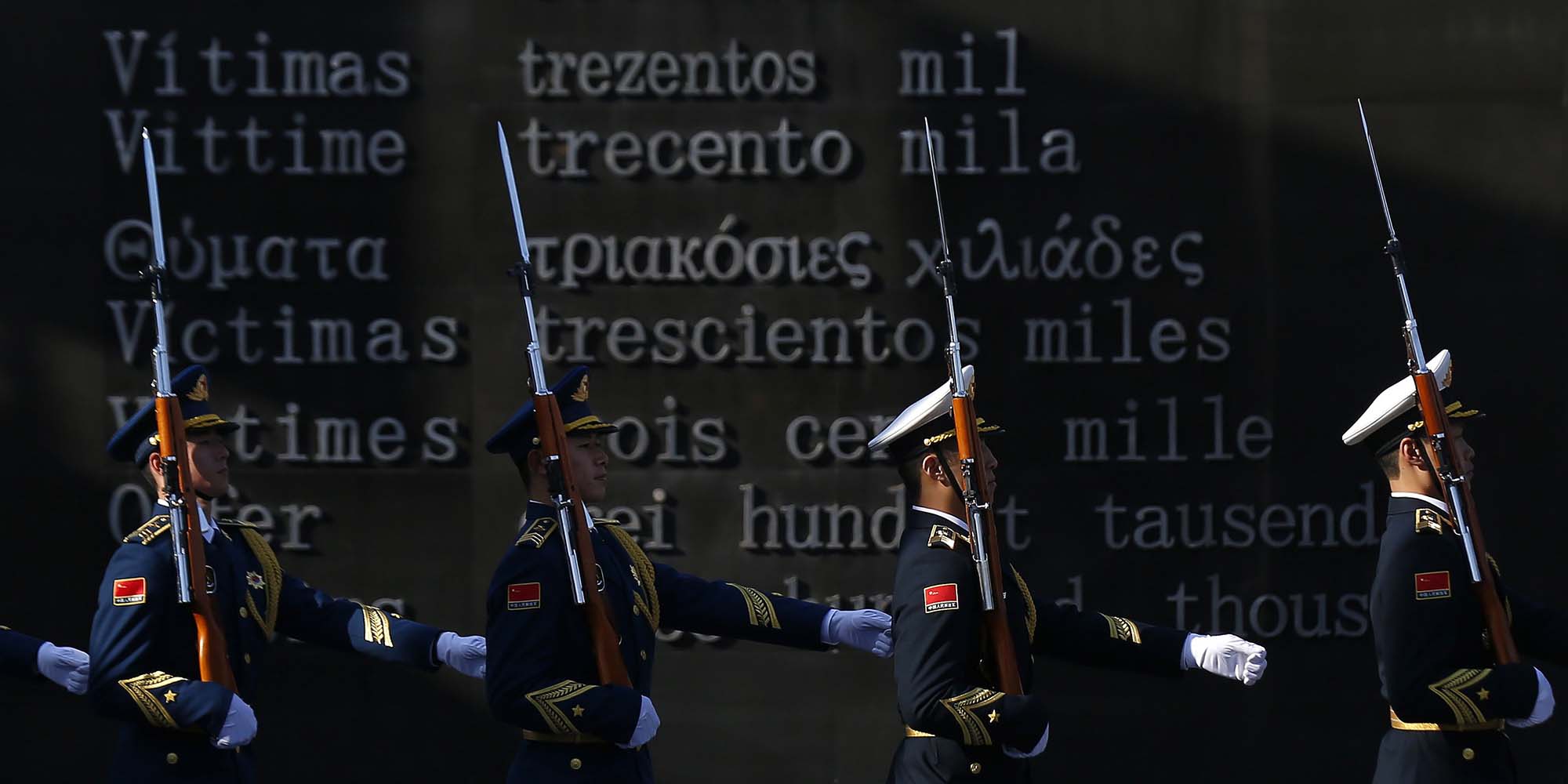

(Header image: People’s Liberation Army (PLA) soldiers march during a ceremony at the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall in Nanjing, Jiangsu province, Dec. 13, 2014. Aly Song/Reuters)