The Enduring Legacy of the Line Between Two Chinas

This article is part of a series looking back at some of the most noteworthy China stories of 2017.

JIANGSU, East China — A two-story lane house built in the early ’30s near Nanjing’s Southeast University has been home to four generations of the Hu family.

In 1935, the house’s first owner — Hu Huanyong, then dean of the geography department at National Central University — drew an imaginary line stretching from Heihe in China’s far northeast to Tengchong in the southwestern corner of the country. In the decades since, this demarcation — later named in Hu’s honor — has taken on great demographic, environmental, and political significance.

For five weeks last spring, Sixth Tone traversed China’s heartland to explore life along the Hu Line. Even when he first imagined the boundary, Hu realized there was a striking difference between what lay to the east and what lay to the west: The latter was home to only 4 percent of the population but accounted for 64 percent of China’s land area — disparities that hold true today. In addition to being more populous, the affluent east is also more homogenous: The overwhelming majority of its inhabitants are Han, while most of China’s ethnic minorities live to the west.

Despite the sweeping economic and social changes that have taken place since its inception, the Hu Line today holds much the same significance as it did 80 years ago and has attracted increasing attention in academic circles.

Hu Huanyong’s grandson Hu Fusun now dedicates much of his time to researching the life of the man behind the Hu Line, who also cultivated a reputation as the founder of Chinese population geography.

Born in 1901, Hu Huanyong lived during the most tumultuous period in contemporary Chinese history, encompassing the Warlord Era, the Sino-Japanese wars, the civil war, and the Cultural Revolution — when he was labeled a counter-revolutionary because of his Nationalist ties and put in prison for five years. In his late 70s, however, he was given the opportunity to resume his research on population at East China Normal University in Shanghai, where he remained until his death in 1998.

“Of my grandfather’s descendants, not one studied geography,” Hu Fusun, a retired consultant, told Sixth Tone. “He had seven children, most of whom ended up in engineering or the sciences — decisions that might have been influenced by the ideological wave after [the founding of the People’s Republic in] 1949.” In Hu Fusun’s opinion, his grandfather’s achievements extend well beyond the contribution of a single invisible line.

Sixth Tone talked to Hu Fusun about his grandfather’s life, the Hu Line, and the boundary’s ongoing legacy. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Sixth Tone: Your grandfather studied in France. How did this influence his research?

Hu Fusun: I think it had a considerable influence. In 1926, he and three of his friends devised a plan: Two of them would stay home in China and work to support the other two as they studied abroad, and then they would switch places. My grandfather was one of the two who went abroad first. His professors were internationally renowned geographers. During his two years of study in France, he said, he was always either in the library or in class. He also felt that the Western education in geography helped him build up his knowledge tremendously.

But he didn’t get a degree. It wasn’t because he was incapable, but because he was worried about his mother back home, as China was in the throes of war. So he wrote a letter to Zhu Kezhen [his Harvard-educated professor in China], who agreed to bring him home. Zhu sent my grandfather money to buy a batch of scientific instruments. He also asked my grandfather to visit several observatories, including the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, U.K.

My grandfather returned to China by train, through Siberia, with the instruments from France in tow. These instruments eventually became part of the Institute of Meteorology on Qintian Mountain in Nanjing. Zhu made my grandfather a professor in the geography department at National Central University immediately upon his return. At the same time, he also worked as a researcher at the meteorological institute.

Sixth Tone: How was the term “Hu Line” first coined?

Hu Fusun: In 1935, when my grandfather published a research paper titled “The Distribution of Population in China” — which included a population density map — it didn’t attract much attention.

My father, Hu Zhizhong, told me that it wasn’t until my grandfather went to Maryland [in the U.S.] as a visiting scholar in 1945 that he learned his discovery was being used in Chinese population research by the international community. They were the ones calling it the “Hu Line” — while back in China, there was no such term.

Sixth Tone: The Hu Line has gained increasing attention in recent years. How do you feel about this?

Hu Fusun: We are surprised by this ourselves. Hu Huanyong first discovered the line when he was a young teacher in his 30s. At that time, the geography department at National Central University had undertaken multiple research projects, including ones commissioned by the national government. For my grandfather, [the Hu Line] was just a general research discovery. But today, it has become a baseline for maps used in the study of meteorology, agriculture, geology, and even seismology.

From today’s perspective, it seems like a great find — and one that I assume exceeded my grandfather’s expectations.

Sixth Tone: What can you tell us about Hu Huanyong’s experience during the Cultural Revolution?

Hu Fusun: During the revolution, his house was searched many times because he had been repeatedly denounced for being “too intimate with the Nationalist Party.” At first, he was forced to sweep the streets at East China Normal University. Later, from 1968 to 1973, he was put under investigation.

My grandfather was “rehabilitated” in 1979. It was impossible for him to continue his research during the revolutionary period, but he stuck to his reading habits, even as the Red Guards kept coming to search his home.

Sixth Tone: Why did you decide to study your grandfather’s life?

Hu Fusun: When my grandfather was alive, we all knew that he was a great scientist. But it’s a pity none of his descendants turned to geography.

After my father retired from teaching and fell ill a few years ago, he would often share stories with me about his dad — my grandfather — and this helped me realize that there should be someone in our family to carry on this research — and so I became quite interested in it. Besides the materials we have at home, I’ve visited large archives and libraries. My interest grows stronger the more I read, both online and off. Today, I think of my grandfather not just as my ancestor, but as a true master of science.

Sixth Tone: Besides the Hu Line, what are some of Hu Huanyong’s significant achievements?

Hu Fusun: In September 1931, my grandfather became the principal of Suzhou High School while he was still the dean of the geography department at National Central University. At first, he only committed to one month — but then came the Mukden Incident [a railway explosion that precipitated the 1931 Japanese invasion]. Amid the general feeling of insecurity spreading across Chinese society, some students and teachers left the school, but my grandfather moved his family to Suzhou to reassure his colleagues, the students, and their families that they would be safe.

My grandfather was quite pleased with his two years as principal at Suzhou High School. Many of his students became leaders in a variety of industries, and they kept in touch with him.

“The country is going through a difficult time,” my grandfather once said to them at their graduation ceremony. “I hope you can take care of yourselves. I have great expectations for you, as you have been cultivated to excel in all areas.” Looking back now, I believe he thought of their success as his success, too.

Additional reporting: Wang Yun; editor: David Paulk.

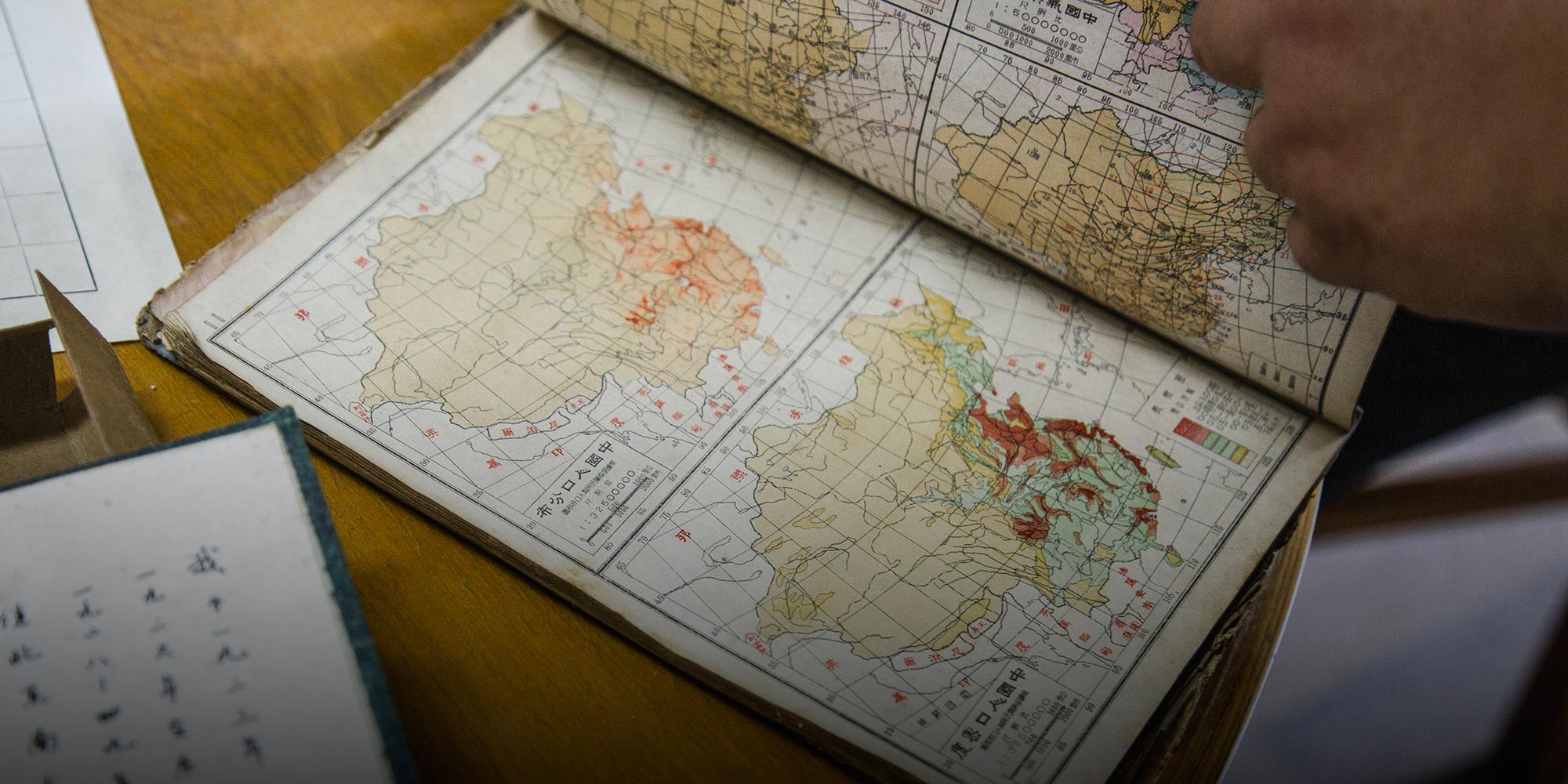

(Header image: Hu Fusun turns the pages of an atlas at the Hu family home in Nanjing, Jiangsu province, July 28, 2017. Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone)