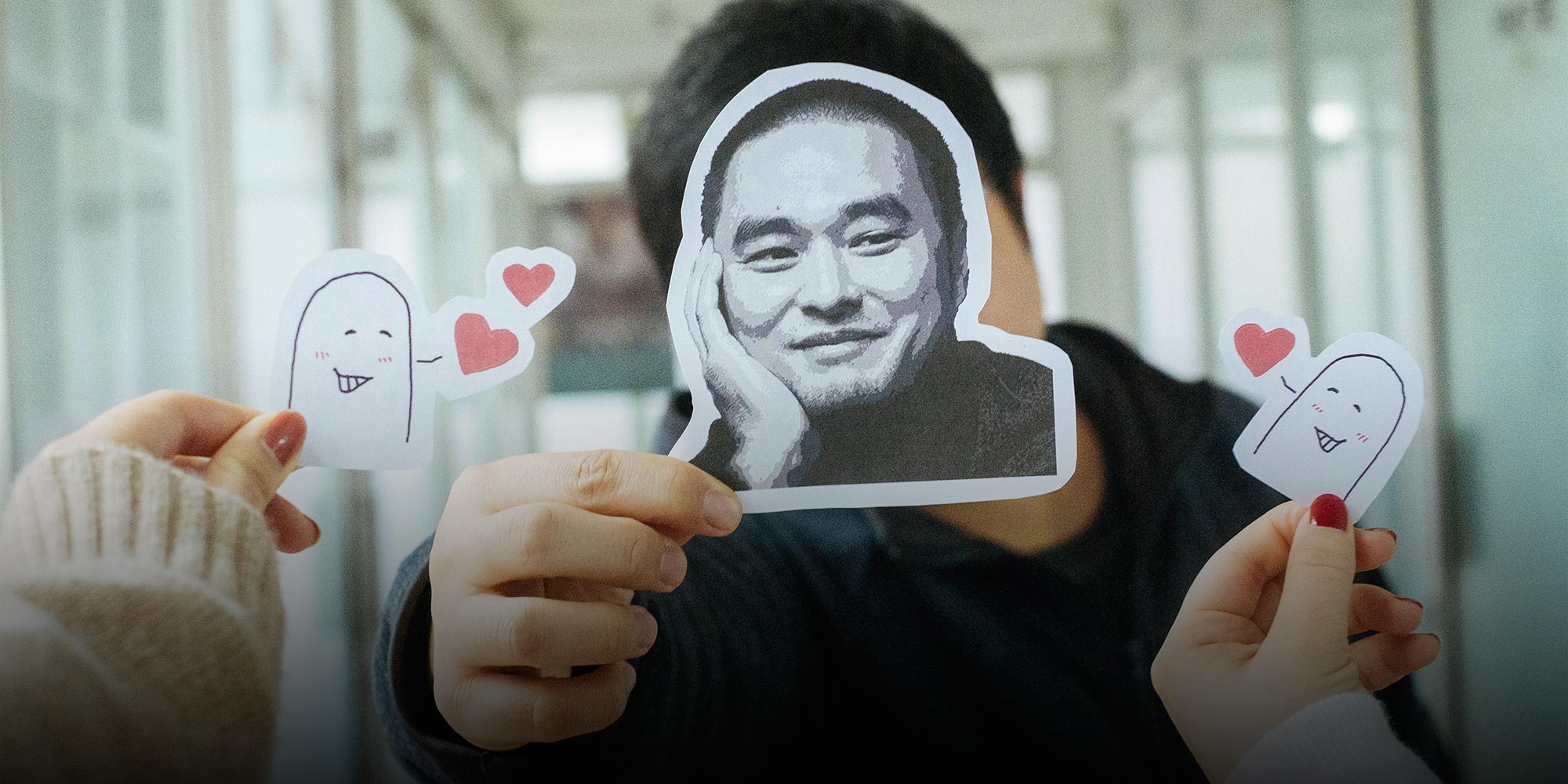

An Awkward, Greasy Year: China’s Top Slang of 2017

This article is part of a series looking back at some of the most noteworthy China stories of 2017.

Every year, novel words and expressions blaze a twinkling trail through China’s social media stratosphere.

These memes can take the form of images, chat stickers, phrases, or even single characters. Their origins include video game jargon, viral articles, reality TV shows, and even old movies.

Once a saying starts trending, it gets lapped up by online media, brand marketers, and even government departments hoping to appear more relatable to younger audiences. It’s all part of the life cycle of China’s teeming online ecosystem.

At the end of each year, Chinese media outlets and even government ministries publish lists of the top memes and expressions from the previous 12 months. On Dec. 18, a language research center under the Ministry of Education officially released its list of the “Top Online Sayings of 2017.”

Below are the translated expressions, along with our explanations.

1. Awkward small talk

尬聊 (gàliáo)

2017 was the Year of the Rooster: a suitable animal for a year in which young Chinese developed a love of all things awkward.

Combining the character ga — most commonly seen in the word ganga, meaning “awkward” — with other characters has created an entire vocabulary dedicated to toe-curling cringe. There’s gawu, “awkward dancing”; gachang, “awkward singing”; and galiao, “awkward small talk.” Galiao can be used as both a noun and a verb — for example, “What are you galiao-ing about now?”

Earlier this year, a middle-aged man burst into spasms of dance when traffic police on the island of Hainan stopped him. The video of the incident became a viral hit, with some netizens adding techno beats to the footage of “gawu uncle.”

2. Do you freestyle?

你有freestyle吗?(nǐ yǒu freestyle ma?)

Last summer, the hugely popular music TV show “Rap of China” nudged hip-hop into the spotlight. In the first episode, one of the show’s judges, Canadian-Chinese pop singer Kris Wu, repeatedly asked contestants whether they “freestyled,” using the English term for improvised rap within an otherwise Chinese sentence.

The expression instantly went viral, particularly online GIFs of Wu asking the question. Before long, netizens all over China were jokingly asking each other, “Do you freestyle?”

Although the meme mocked Wu, he enjoyed a massive boost in popularity as a result of the show, and has since netted a string of endorsement deals for brands such as fashion house Burberry and cellphone maker Xiaomi.

The show also popularized a number of other terms, such as the English hip-hop culture term “diss” — meaning “to show disrespect” — and terms from Chinese dialects, such as Sichuanese, that appeared in rap songs.

3. Call for support

打call (dǎ call)

This term, which again mixes Chinese and English, is often misinterpreted as meaning “to call someone,” but in fact it’s used to rouse support.

The phrase originates in Japanese pop culture. During live concerts, singers often gesture for audience members to wave glow sticks in time with the music — a “call” for fans to wave in unison.

Later, influential Chinese social media accounts adopted the term and it became used more widely, eventually becoming a rallying cry for anything: a brand, a person, or a phenomenon.

During the Party’s 19th National Congress in October, the Weibo account of the Communist Youth League, a state-run youth organization, posted an image mosaic of nine quotes from President Xi Jinping’s opening speech. “Today, let us encourage ourselves and da call for the ‘new era,’” read the accompanying text, ending with a popular catchphrase to emerge from the weeklong event.

4. Pipi Shrimp, let’s go!

皮皮虾我们走 (Pípí xiā, wǒmen zǒu)

GIFs depicting a comic figure riding some sort of creature with the slogan “(Creature’s name), let’s go!” emerged as early as 2015, with an early version depicting a boy riding a monster from a collectible card game.

In 2017, a variant of the meme featuring a boy on a giant mantis shrimp shouting “Pipi Shrimp, let’s go!” went viral. Online sticker sets soon began to include their own crustacean-riding variations.

The sticker has been popular because it is cute, absurd, and versatile: Use it to say goodbye in a group chat, or when you’re leaving an argument in a huff.

5. That hurts, bro.

扎心了,老铁 (zhāxīn le, lǎotiě)

This meme originated from bullet screen comments on video-streaming sites. Laotie is a term from China’s northeastern dialects, meaning “buddy” or “bro,” while zhaxin literally means “to pierce the heart.” The phrase is often used humorously to feign heartbreak.

In August, a humorous Weibo post about a wife whose saucy dreams of amorous liaisons with a literal line of men were revealed through her sleeptalking was liked over 30,000 times. The post was titled, “Your wife had a bad dream, hahahahahahaha, that hurts, bro.”

6. Surprised? Shocked?

惊不惊喜,意不意外 (jīng bù jīngxǐ, yì bù yìwài)

A quote from the 1992 Hong Kong movie “All’s Well, Ends Well,” this expression is often used to mock dramatic plot twists in TV series, but it can also apply to other shocking events.

Recently, the Dallas Mavericks, an NBA team that is also popular in China, used the phrase on its Weibo microblog account to describe a clip of a player scoring a crucial basket in the final seconds of a game.

7. Doesn’t this hurt your conscience?

你的良心不会痛吗?(nǐ de liángxīn bù huì tòng ma?)

This expression arose from an article on social media pointing out that Tang Dynasty poet Du Fu wrote 50 verses dedicated to his contemporary, Li Bai, while Li reciprocated with very few — and even wrote a famous ode to another poet. In the comments, users jokingly asked, “Li Bai, doesn’t this hurt your conscience?”

The expression was later popularized after it appeared in a sticker set of the Poinko Brothers — two chicken-like puppets who flapped their way to fame earlier in the year, as China welcomed the Year of the Rooster. But it turned out that the fowl pair were in fact parrots from a 2015 series of promotional videos for a Japanese telecommunications company.

8. Fight back!

怼 (duì)

Dui is an infrequently used character that originally meant “resent” or “bear a grudge,” but this year it has become a popular expression meaning “bite back” or “retort.”

The word, which is more commonly used in dialects, can be deployed in a wide range of scenarios. If your car is dui, for example, it was hit. In video games, players call on teammates to dui, or kill, their enemies.

9. You can even do that?

还有这种操作?(hái yǒu zhè zhǒng cāozuò)

Coming from the world of esports, where it was used in response to an impressive move or trick in a video game, this phrase later became a generic expression of incredulity, usually in the form of a sticker.

Along with a photo of a white-collar fashion innovation — a garter for keeping men’s dress shirts tucked in and well-kempt — one Weibo user expressed his amazement at finding such a whimsical item: “You can even do that?”

10. Greasy

油腻 (yóunì)

In October, an article by doctor-turned-blogger Feng Tang titled “How to avoid becoming a greasy, dirty middle-aged man” gained 6.3 million views on social media app WeChat.

The article called out middle-aged men for their unsavory tendencies, such as being sleazy and unkempt and putting down younger people. Many hit back at the writer, saying he was a greasy middle-aged man himself.

Although the term was already in existence, hot takes on “greasy” conduct in all demographics mushroomed after Feng’s article — for example, calling out middle-aged women for gossiping, or young people for showing off on social media.

Editor: Qian Jinghua.

(Header image: Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone)