Long Hours Lead to Labor Disputes for China’s Startups

The “996” culture that pervades China’s tech industry — working hours from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week — is resulting in management problems and even lawsuits for many startups, a recent report found.

While employees at many startups work nonfixed hours that include lots of overtime, more than 40 percent of such companies lack clear rules on paying for the additional work or compensating it with time off, the report says. It identified this problem as the thorniest management issue faced by the young companies — ahead of salary, social insurance, or employee training.

The report on the employment risks of China’s early-stage enterprises was published Friday by Wusong Network Technology Co. Ltd., a Beijing-based law consulting company, and China Growth Capital, a venture capital firm.

According to Chinese law, companies that forego the standard eight-hour work day and adopt flexible schedules should get approval from the local government department in charge of human resources. “It’s common practice, but many startups don’t realize that they have to get approval from the labor administration department,” Jiang Yong, the founder of Wusong, told Sixth Tone.

Ninety-nine internet startups yet to undergo a third financing round were surveyed for the report beginning in April of this year. They include companies in the fields of e-commerce, business-to-business services, finance, and artificial intelligence, most of which are based in Beijing, Shanghai, or the relatively affluent coastal provinces of Guangdong and Zhejiang.

The most common labor disputes faced by these startups involved terminated contracts (accounting for 35 percent) and salaries and bonuses (accounting for 16 percent). More than 20 percent of the disputes end up in court or arbitration, according to the report, a brief of which Wusong sent to Sixth Tone.

“Because of the high [price] of legal services, most of the startups are unable to hire full-time, in-house lawyers or get solid advice from legal professionals,” Jiang said, adding that when it comes to legal risks, many startups are just “running around naked.”

Last year China’s largest site for classified ads, 58.com, adopted the 996 work schedule, with employees only getting Sundays off. They complained publicly, but the measure was nevertheless adopted, with other tech companies following suit, especially during peak periods.

Gu Huitao, a 27–year-old working at an online advertising startup, told Sixth Tone that he usually leaves his office around 7 or 8, and sometimes works on the weekends. “We don’t have a bonus for overtime, but if we work late, the bosses might treat us to a late-night snack, or allow us to arrive later the following morning,” he said. As the father of a 1-year-old child, Gu values his free time — so much so that he turned down an offer from a shared-charger startup last year because that company operated under a 996 work schedule.

Despite their inherent challenges, startups are mushrooming in China. Since 2015, Premier Li Keqiang has frequently called for “mass entrepreneurship,” which local governments across the country have responded to by offering startup subsidies and building incubators. In 2016, 5.5 million new companies were registered nationwide, an increase of 25 percent compared with 2015.

Editor: Kevin Schoenmakers.

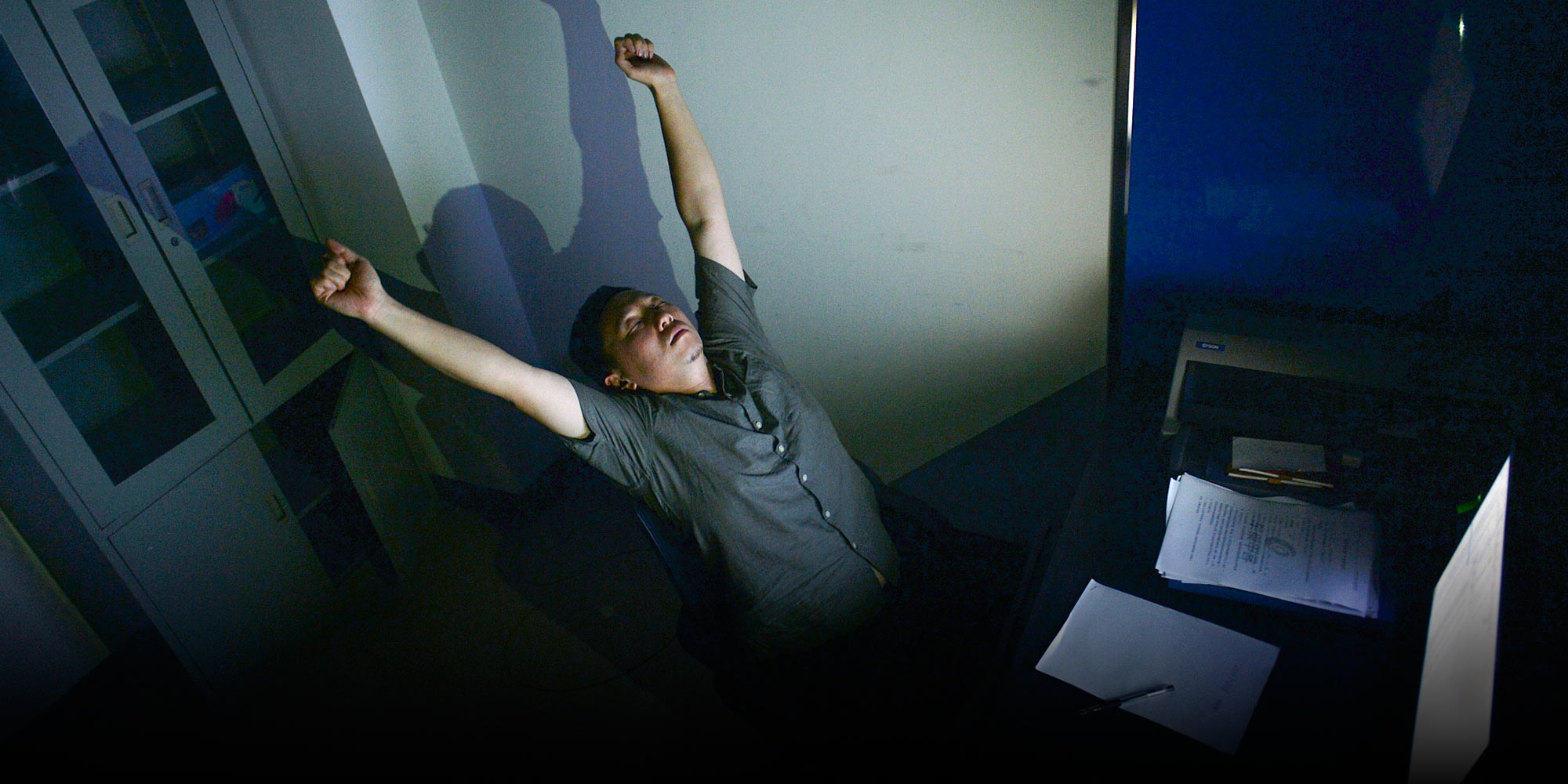

(Header image: An employee at a startup company stretches at his desk while working late in Shijiazhuang, Hebei province, June 22, 2016. Chen Jianyu/VCG)