40 Years of ‘Gaokao’ After Mao

Though it was winter when China’s national college entrance exam — the gaokao — resumed in December 1977, none of those who sat the test mentioned the cold when they spoke to Sixth Tone about their experiences. It was a sunny day, they recalled. Their excitement overrode everything else, as the chance to attend college finally appeared within reach after a decade of fierce anti-intellectualism.

The gaokao started in 1952, but when the Cultural Revolution began in 1966, the exam was canceled. High schools and middle schools in China’s cities stopped teaching as students left class to answer Chairman Mao Zedong’s call for revolution and then were sent to labor in rural communes.

Members of the demographic that would have graduated from high school between 1966 and 1968 are called laosanjie. Literally translated as “old three classes,” the term identifies the generation that both propelled and endured the most feverish heights of the Cultural Revolution.

From 1968 to 1976, universities reopened, but only to students recommended by their Communist work units — a path dependent on having a blameless proletarian family background. In 1973, a test was added to the recommendation system, but the results were disregarded following a political outcry that the test was elitist.

The gaokao was finally reinstated on Dec. 10, 1977, more than a year after Mao’s death. These days, the gaokao takes place in early June, and more than 70 percent of candidates — mostly high school students — secure college admission. But in 1977, only 5 percent of the 5.7 million people who took the exam were admitted to college. Most were already in their 20s, or even their 30s.

Many of the country’s current power brokers and luminaries were part of the 1977 cohort, including Premier Li Keqiang and celebrated painter Luo Zhongli. They emerged from adolescences in one of history’s most volatile periods to form the backbone of culture and politics in contemporary China.

Like Premier Li, Liu Bingkang hails from Hefei, the provincial capital of Anhui in eastern China. Now 65 years old and a professor of architecture at Hefei University of Technology, Liu is one of 15 million laosanjie whose schooling was disrupted during the Cultural Revolution. His experience of sitting the 1977 gaokao exemplifies that of a generation hungry for knowledge after being deprived of higher education for a decade.

This is his story, as told to Sixth Tone and edited for brevity and clarity.

When the Cultural Revolution began in 1966, I was in my second year of middle school in Hefei, and classes stopped. Like many others, I was sent to the countryside in 1968. Two years later, I came back to Hefei to work as a carpenter in a construction company.

I knew I wouldn’t get into college based on the recommendation system because I had a “bad” family background: My father was an intellectual, a professor at Anhui Normal University, and they accused him of working in “reactionary organizations” before the establishment of the new China. But I didn’t give up.

Even before 1977, I secretly studied with my colleagues, who were all educated youth. Publicly, we set up philosophy study groups and read books by Karl Marx and Mao. Privately, we exchanged any books we could find, such as [Leo Tolstoy’s] “Resurrection” and [Charlotte Brontë’s] “Jane Eyre.” Back then, you’d be condemned for lacking revolutionary spirit if you were found reading these books.

I searched for textbooks everywhere. At the time, books were rare, so it wasn’t easy. I bought a series of advanced mathematics textbooks with Mao quotations printed all over them, and worked through half of the series. People mocked me, saying I was “on the path of anti-socialist professionalism,” but I believed that the knowledge you learn is yours. It will not fail you.

Sixth Tone: The term “anti-socialist professionalism” was used to denounce people who focused on academic research or professional expertise without taking a political stance during the Cultural Revolution.

When the news came in October 1977 that the gaokao would resume, I applied without further thought. By then, I was already 25 years old.

Everything happened in a rush. We had less than two months between when we registered and when we sat the exam, so you had to rely on what you’d already learned. We heard the exam papers were printed at the same factory that printed copies of the “little red book” [of Mao’s quotations].

Sixth Tone: Each province had its own exam papers in 1977, but there was no distinction between humanities and science students like there is in most provinces now. That year, universities in Anhui only accepted students from within the province. For candidates in Hefei, the exam took place at Hefei No. 9 Middle School.

I rode a bicycle for half an hour from my workplace to the school to take the exam, and went back to the company for lunch. It was a simple event, not like it is now.

Over two days, I took four exams: Chinese, mathematics, politics, and physics. I felt lucky that chemistry wasn’t included, or I wouldn’t have done so well, as it’s very hard to learn chemistry without a lab for experiments. My knowledge of advanced mathematics helped as well. To calculate an extreme value, I used derivation, which I’d learned through self-study.

There were two essay topics to choose from in the Chinese exam. The first was on Mao’s legacy: “Follow Chairman Hua; sing ‘The East Is Red’ forever.”

Sixth Tone: Chairman Hua Guofeng was Mao’s successor, and “The East Is Red” is a song praising the leadership of Mao and the Communist Party. Adapted from a folk melody, it was widely sung during the Cultural Revolution — when the national anthem was less popular because its writer, Tian Han, had been falsely denounced as a traitor.

The other essay prompt was an excerpt of a poem by Ye Jianying, one of the founders of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army: “The road to science is dangerous and difficult; only by fighting hard can you break through.” That’s the one I chose.

Around 40 people in my company took the test, and I was the only one accepted to university. Several others went to vocational schools.

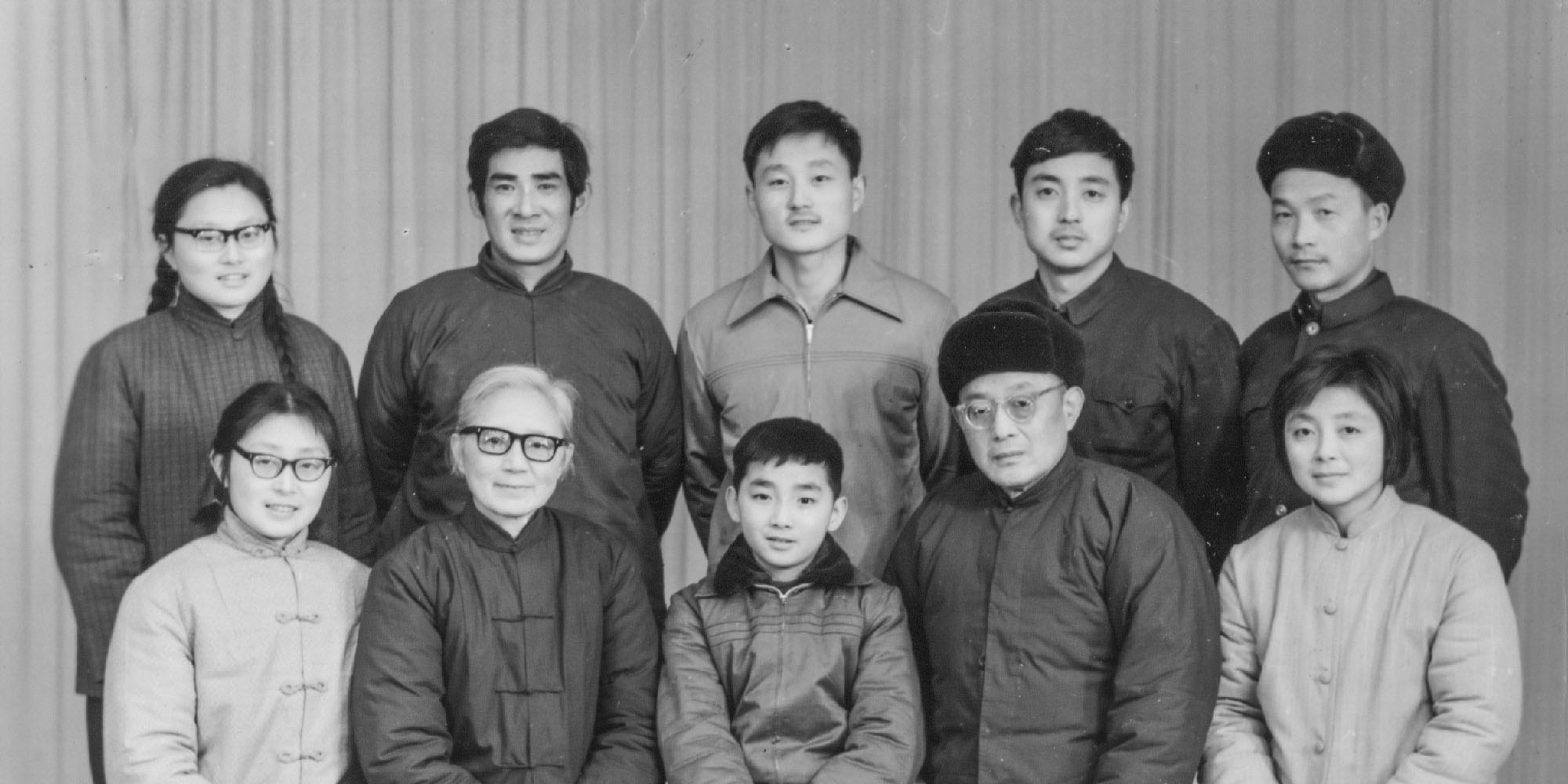

It was an important time for my family. When the admission letters came before the Spring Festival [in February 1978], we were so delighted to learn that my younger brother, my younger sister, and I were all accepted to college.

The news quickly spread through our community. Neighbors told us our ancestors must have blessed us from the tomb. Some said it was because we had come from an intellectual family — family background became important again, but in a different way. My parents, who had felt guilty that we couldn’t go to college because of their background, were very pleased.

But I was already 25 years old. I had applied for a major in teaching mechanics, but I was admitted to the industrial and civil architecture program because the school thought it suited my background [in the construction company]. I had no problem with that — I was happy to study anything.

Sixth Tone: Though candidates in 1977 could submit their course preferences, they were sometimes directed toward other majors based on the country’s needs. As the universities themselves were short-staffed, many of the available courses were for future teachers.

Our major had 72 students across two classes. Most of my classmates had been born in the mid-’50s and had endured numerous hardships in factories or in the countryside. Some were more than 30 years old and already had children.

Before the Cultural Revolution, the education system was imported from the Soviet Union. When I went to college, it was still the same. Most textbooks were old, and in the first month, we did not have textbooks for some subjects because they hadn’t been printed yet.

People who go to modern book stores would not have imagined that back then, whenever books arrived at the store on campus, students would rush to buy them. Books were so rare that no matter what they were, we felt they must be beneficial to our studies.

The campus living conditions were rough: We had seven people in our dorm but only four beds, so people had to share beds. The canteen food was poor quality, too. But despite the lack of resources, all the students worked hard, to an extent that students today could neither imagine nor understand. We were like hungry wolves craving knowledge, thanks to years of suppression.

The doors of our study building would close at 11 p.m., so some students would stay in the classrooms until the next day. The lights of the dorms would go out at 11 as well, and students would go into the hallway, where there was still light, to read. Girls with long hair found combing their hair time-consuming, so they cut it off.

I got married after graduation, when I was 30 years old. In 2000, my son took the college entrance exam. When he saw the test questions we had on the [1977] gaokao, he laughed at how easy they seemed. It’s true: The questions we had were much easier than the questions today. But getting into college was much harder then. Only 200,000 of the 5.7 million people who took the gaokao that year were admitted to college. Today, there are more annual doctoral admissions than that.

After graduating with distinction, I stayed at my alma mater as a professor and have devoted myself to teaching and researching in the field of architecture ever since. Sitting the gaokao in 1977 fundamentally changed my life.

Editor: Qian Jinghua.

(Header image: A family photo shows Liu Bingkang (back row, second from right) during the 1978 Spring Festival. Around that time, Liu, his brother, and his sister all received college admission offers. Courtesy of Liu Bingkang)