Reliance on Foreign Tech Puts Strain on China’s Genetics Market

In 2007, Shanghai launched a project called Eastern Scholars, which provided funding to lure distinguished academics to the city to reinvigorate academic programs at top universities. The program provided the impetus for my 2009 move to Fudan University, where I ran the nanofabrication lab. Now, however, my goal is to provide the technology necessary to treat diseases using DNA sequencing. In the next couple of years, I hope to make this a viable option for the majority of Chinese patients, and as quick and easy as drawing blood.

After three years as an Eastern Scholar, I decided in April 2015 to start my own gene sequencing company, Turtle-Tech. The name is a play on words: In Chinese culture, turtles are symbols of longevity; in Chinese language, the word for turtle — haigui — can also refer to someone who returns to China after studying abroad. This reflects my own experience as a student in Sweden, where I worked on a project to develop a gene sensor using semiconductors.

Genetic testing allows scientists to examine a person’s DNA from, say, a blood sample. In addition to providing medical diagnoses, it can also be used to see how likely it is that someone will contract a given disease in their lifetime. It can even be used in cancer screenings, to test a patient’s susceptibility to certain types of cancer, and thereby help them to prolong their life. Currently, there are over 1,000 diseases that can be diagnosed using genetic technologies.

The DNA sequencing industry has grown rapidly in recent years, with the global market for sequencing services growing from $7.94 million in 2007 to a predicted $11.7 billion by next year. It is estimated that this market will continue to grow by more than 20 percent annually over the next 10 years.

In China, DNA sequencing services began popping up online as early as 2006. Since 2009, health management centers at some of the country’s top-ranked provincial and municipal hospitals have offered genetic testing as part of physical examinations. The barriers for clinical application remain high, however, due to the fact that the genetic testing industry and its products still constitute “medical instruments requiring supervision.” In practice, this means they are required to pass clinical trials and be approved by the China Food and Drug Administration (CDFA) before they can be used for medical purposes.

People soon discovered, however, that although the barriers to clinical use are quite high, DNA sequencing holds a potentially vast commercial value. In advertising, such technology is frequently portrayed as having almost miraculous effects: It can prevent illness, help you lose weight, unearth hidden talents, even trace your ancestry. The fact that current technology is not mature enough to guarantee these benefits does little to persuade people that a product this impressive won’t be in high demand in the future.

In China, there are currently two main types of sequencing companies in the industry. Most of the first kind entered the market more than five years ago; they include companies like BGI, NovoGene, Berry Genomics, and BasePair. These companies largely emerged out of the scientific research industry, and are primarily focused on offering medical testing services. The second kind consists of companies that have entered the market in the past two years. This group, which includes the likes of WeGene, G-Cat, Somur, M+ Gene, and QuantiHealth, primarily market their technology to ordinary consumers.

Recently, in the battle for market share, the second set of companies have started diversifying their products. Now, in addition to letting consumers test their own DNA, they are also engaged in a major price war, with tests costing only 300 to 400 yuan ($43 to $58). They also offer products aimed at weight loss, nutrition, fitness, and early education.

Against this background, newcomers to the market immediately find themselves on their heels. First, if you want access to the medical testing market, your product must win approval from the CFDA, after which you still need to come up with a way to persuade hospitals to buy your products. If the commercial market tickles your fancy, you have to face up to a nagging doubt at the back of consumers’ minds: Is genetic testing actually of any use to me?

The number-one barrier to the growth of the genetic testing industry is one of knowledge. While China has made impressive strides in the field of DNA sequencing, its data capabilities have yet to catch up to more developed countries, and China still lacks a national DNA database. This data is important for carrying out research and developing our overall knowledge of genetics. Those of us involved in bioinformatics essentially turn that raw data into knowledge, then use this knowledge to make inferences and deductions about human health.

But certain limitations are keeping genetic testing from living up to its full potential. At present, DNA testing kits run anywhere from a few hundred to a few thousand yuan, but according to some radical viewpoints, they should be made totally free to anyone who wants them. The problem is that the exact implications of genetic testing results are not yet clear. While gene editing technology makes for enticing headlines, it is not ready for widespread use as an method for curing disease.

As a leader in DNA sequencing, China began adopting the “precision medicine model” — which focuses on making health care customizable and personalized — only a few months after the United States. Currently, the two countries are keeping pace with one another in this field. However, due to an effective duopoly on key technologies by American companies Illumina and Life Technologies, China is restricted in its research into DNA sequencing and treatments involving genetic manipulation.

The development of DNA sequencers and their accompanying chemical reagents is largely dependent on foreign capital, with the two aforementioned American firms having achieved dominant positions within the industry. Their market dominance is compounded by the continuous rise in prices of key materials and reagents. The price of a single gram of imported polymerase — the enzyme that builds DNA — is comparable to that of gold. Creating a domestic variant of polymerase, however, would mean Chinese companies could lower this price significantly. By developing homemade versions of the necessary machine components, sequencers could be produced for around one-third of what they cost to make overseas, and possibly even less.

The initial wave of startups since 2015 has now receded, and the Chinese genetics industry is undergoing a lull in investor interest. DNA testing itself has also entered an awkward phase, with domestic and foreign research organizations having hit a technological plateau. Given the inherent limits of genetic technology, it may be necessary to wait until both it and the market has matured further before it can reach its full potential. For me, personally, I hope that my little Turtle-Tech can stay afloat through these rougher waters, and that we will be ready to offer competitive products to the Chinese genetic testing industry when the tide finally does come back in.

Translator: Kilian O’Donnell; editors: Lu Hongyong and Matthew Walsh.

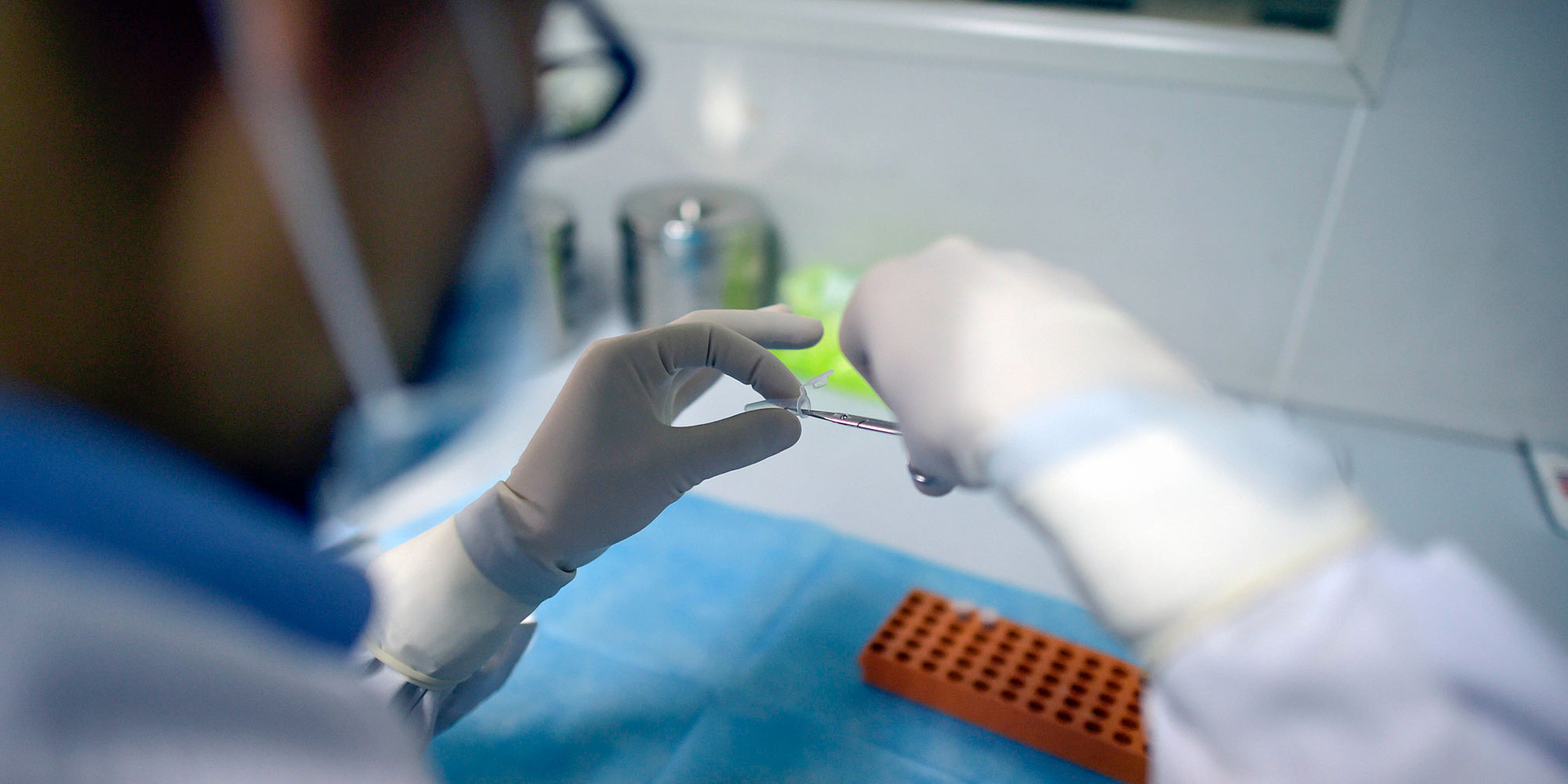

(Header image: A laboratory technician transfers a sample for a genetic test in Chongqing, April 9, 2015. VCG)