Temples Put Profits Over Enlightenment

Last year I attended a conference in Shanghai on Buddhism, where I met a member of the Buddhist Association of China. We got to talking, and I asked how many Buddhist temples there are in China and how many monks occupy them. He told me that the latest figures were around 30,000 temples and 80,000 monks.

Although there are no official figures for the country’s monk population, the State Administration for Religious Affairs reports that as of 2015 there were 28,247 registered “Chinese-language Buddhist venues for religious activities” in China. Of course, these numbers may be misleading. Since the official number of temples only accounts for those that are formally registered, the actual number may exceed the official one.

It is also difficult to place an exact figure on monks. The number is determined by how many registration certificates have been issued, but these certificates stay with the monks and are still included in the census even if they decide to leave the monasteries and pursue a secular life.

This means that according to official reports, there is roughly one monastery for every three monks.

And yet, new shrines continue to pop up all over the country, the budgets for some of which are staggering. It would seem then that it wouldn’t be hard for a monk to find a home. But even with tens of thousands of temples dotting China’s map, many monks are still having difficulty finding suitable places in which to settle into a monastic life.

What’s the reason behind all this? Since some of the temples are businesses in the sense that they require investment, management, and are affected by fluctuations in the economy, it may be helpful to compare them to corporations to better understand how they are run. In China, there are several types of business entities, including state-owned, collective, private, and joint-stock.

[node:field_quote]

In China, all land and historical buildings are owned by the state, and this includes all of the famous ancient temples. The government doesn’t necessarily need to see a profit return on historical landmarks, but in some cases they are constructed in strategic locations to boost the local economies by attracting tourism.

Although collectively owned corporations — that is, businesses owned by their workers — are rare in modern China, many temples remain communally owned. Villages sit at the bottom of China’s administrative hierarchy and are self-run by the local residents. Thus, many temples funded and built by villages are actually owned by the villagers themselves.

Monks who take up lodging are often restricted by locals who seek to take a strong hand in managing the monasteries. They will try to make a profit out of the construction projects, or take a piece out of the public donations religious venues heavily rely on.

“Joint-stock temples” are unique in that they are financed by outside investors, who jointly own the temple and run it like a business. These investors will find monks to manage the temple with a sole focus on profit.

Temples that are owned privately are usually small places of worship built by an individual who seeks to attain a personal spiritual profit. The individuals will shave their heads and take up residency themselves or find a monk to reside there.

Some of these for-profit temples have even been involved in widely publicized scandals. According to a report published on May 16, 2013, in the Southern Weekly newspaper, a management committee abused their positions to make money off a temple in Xian, in northwestern China’s Shaanxi province. They reportedly built a big project near the temple, installed men in it who posed as monks, and embezzled public donations.

Attempting to extricate themselves from all of this, some monks end up building their own places of worship. But they face two chief problems.

First, it is costly to build a temple, and donations don’t provide much support. Learning and practicing Buddhism may be good for the soul, but monks still need to eat.

Second, even if they do manage to scrape up the construction and management costs, the monks will face a lot of pressure from outside entities. Large state-owned temples may try and strike mergers or villagers may set up outside the holy walls and sell overpriced souvenirs. All of this disrupts the normal operation of the temple.

The ultimate problem facing society is that most people value economic gain far more than faith. This is even true with donors, many of whom simply give money for a personal vindication: seeking fortune, safety, and good health. Their motivations often have little to do with true, selfless faith.

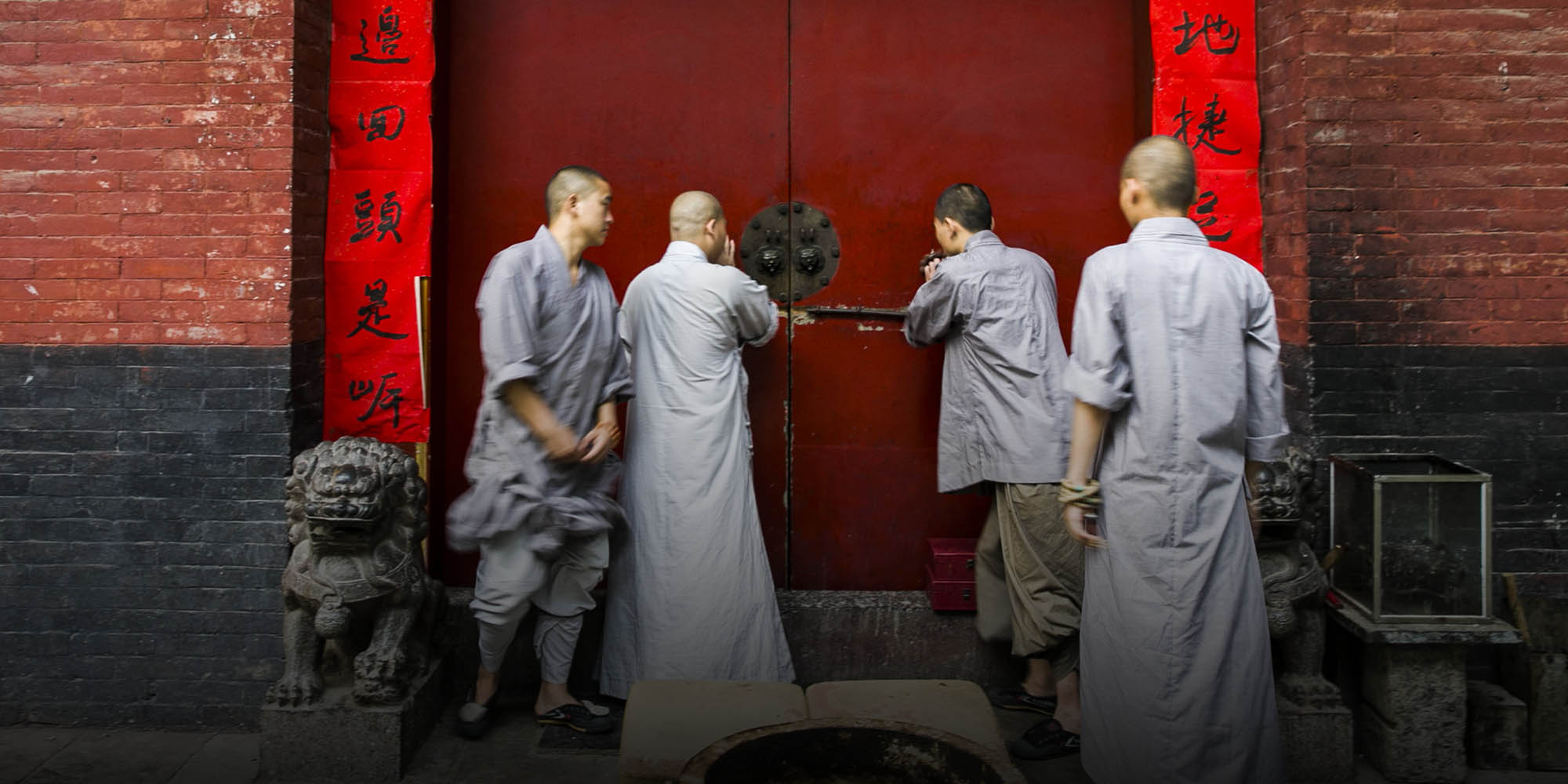

(Header image: Monks stand next to a gate at the Shaolin Temple in Henan province, July 31, 2015. Chen Wei/VCG)