Incomplete and Opaque: The Problems with China’s Porn Laws

This article is part of an ongoing series examining erotic culture in modern China.

The Chinese government has adopted a zero-tolerance policy toward so-called sexual content. Commonly defined as sexual, pornographic, and obscene material, the production, dissemination, and sale of such content, as well as other related behaviors, are forbidden under the law of the land. For the state, these crimes run counter to Article 24 of the Chinese constitution, which asserts that “the state strengthens the building of socialist spiritual civilization.”

As Chinese society has become more open, a debate has developed over the legal status of sexual content. The country’s criminal law, enacted in 1997, refers to obscene material as “publications, films, video and audio recordings, and images containing depictions of sexual acts. Works related to human physiology and medical knowledge are not obscene. Artistic works containing pornographic content are not obscene.” In practice, however, such content remains difficult to define in certain situations. Some of the legislation in current use is still based on ideas of asceticism or abstinence that better reflect social views of sex from 20 or 30 years ago.

The government’s approach is to actively block pornographic content rather than leave it lying around. As a result, China throws significant judicial and administrative resources into frequent pornography-cleanup campaigns, often with mixed results. Two particular problems plague these crackdowns: selective enforcement of the law — often as a result of official corruption — and enforcement strategies known as “fishing,” which attempt to entrap lawbreakers.

For example, crackdowns typically target illegal sexual services provided to ordinary citizens by massage parlors and street prostitutes but rarely go after those that offer services to the elite. Luxury hotels and clubs, which often operate under the protective umbrella of the police, army, or other enforcement agencies, are less likely to be raided.

Additionally, as information on the internet is exceptionally difficult to police, online crackdowns are becoming harder and costlier to carry out. This has led many in China’s legal circles to call for a gradual reform of the nation’s official stance on sexual content. According to current law, in order to determine whether online pornographic content qualifies as obscene material, investigators must consider three factors: the extent to which it was disseminated, whether it was uploaded to make a financial profit, and the severity of its effects.

Over the past 10 years, obscene and pornographic content has spread rapidly across the web. In late 2004, the Chinese government shut down the 99 Erotica forum, a site responsible for disseminating a large quantity of obscene material and whose primary revenue source was fees charged to registered members. In October 2005, the individual who ran the site was sentenced to 12 years in prison, and an additional 10 defendants were given sentences ranging from three to 12 years.

The 99 Erotica case stands in contrast to the case of video-hosting company Shenzhen QVOD Technology Co. Ltd. that was eventually settled in September this year. Back in April 2014, the national office charged with cleaning up pornography and eliminating illegal publications — in conjunction with the Shenzhen Public Security Bureau, the Ministry of Industry and Information and Technology , and other departments — launched an investigation into QVOD for allegedly disseminating pornographic videos.

Officials argued that company CEO Wang Xin and four other defendants were fully aware that QVOD’s media server installation processes and media player were being used to spread, search for, download, and play obscene videos, and that the company allowed this usage in order to profit from it. This led to a large number of obscene videos being disseminated on the internet and had a negative impact on society, officials said. In light of these allegations, QVOD was fined 260 million yuan (about $37.8 million), and its company heads prosecuted. QVOD later appealed the decision.

The disagreement between QVOD and the original prosecutor, the Shenzhen Market Supervision Administration, centered on four points: whether the administration had the authority to levy the punishment, whether the enforcement process was lawful, whether the “civil wrong” committed by QVOD actually harmed the public interest, and whether the size of the fine was appropriate.

On Sept. 13, 2016, the People’s Court of Haidian District, Beijing, issued a preliminary judgment ruling that QVOD had violated the law by disseminating obscene material for a profit. The court decided on the much-lighter punishment of a 10 million yuan fine against the company. Wang Xin and other high-ranking executives were also fined and given sentences ranging from three to three and a half years.

The punishments meted out in QVOD’s case demonstrate the more lenient social attitudes toward pornography in China today. Yet the case also reveals the current shortcomings of China’s pornography laws. A debate continues in criminal law circles as to whether the actions of the defendants constituted criminal offenses; whether what QVOD did actually qualified as disseminating obscene videos; whether QVOD permitted its site to be used for the dissemination of obscene videos; and whether the company profited from these actions.

Another debate centers on whether the viewing of sexual content by adults, in a way that does not influence the interests of others, should be restricted. In 2002, a couple from northwestern China’s Shaanxi province was arrested for watching pornography in their own home, an action that aroused the ire of Chinese legal professionals. When it comes to consenting adults viewing sexual content in the privacy of their own homes, more-liberal lawyers argue that the government should not interfere. However, more-conservative lawyers believe that relaxing the existing prohibition would damage social conceptions of ethics and morality, thereby endangering the supposed moral core of society.

There is a case here for strengthening the rule of law with regard to pornography regulations. First, there is currently no single set of legislation governing issues related to sexual content. Instead, the government’s legal approach is characterized by numerous rules spread across disparate official policies and industry regulations; subjective legal standards that change constantly; and significant discretionary power accorded to investigators.

As a result, legal professionals do not know where they stand in relation to the law. To address this, the government could first clarify the legal standard for investigating sexual content. Additionally, as the institutions that supervise sexual content remain opaque, we should consider establishing more transparency and opportunities for redress. Due process must be respected throughout, and law enforcement must be open, just, and fair.

One interesting way pornography laws could be reformed is by establishing a ranking system for sexual content, adapting the one currently used for commercial films. This system would be tailored to China’s current conditions and ethical and moral standards, and the organization responsible for the rankings could be regularly audited, allowing the government to actively incorporate new technology, improve efficiency, and ensure that the system reflects our ever-changing society.

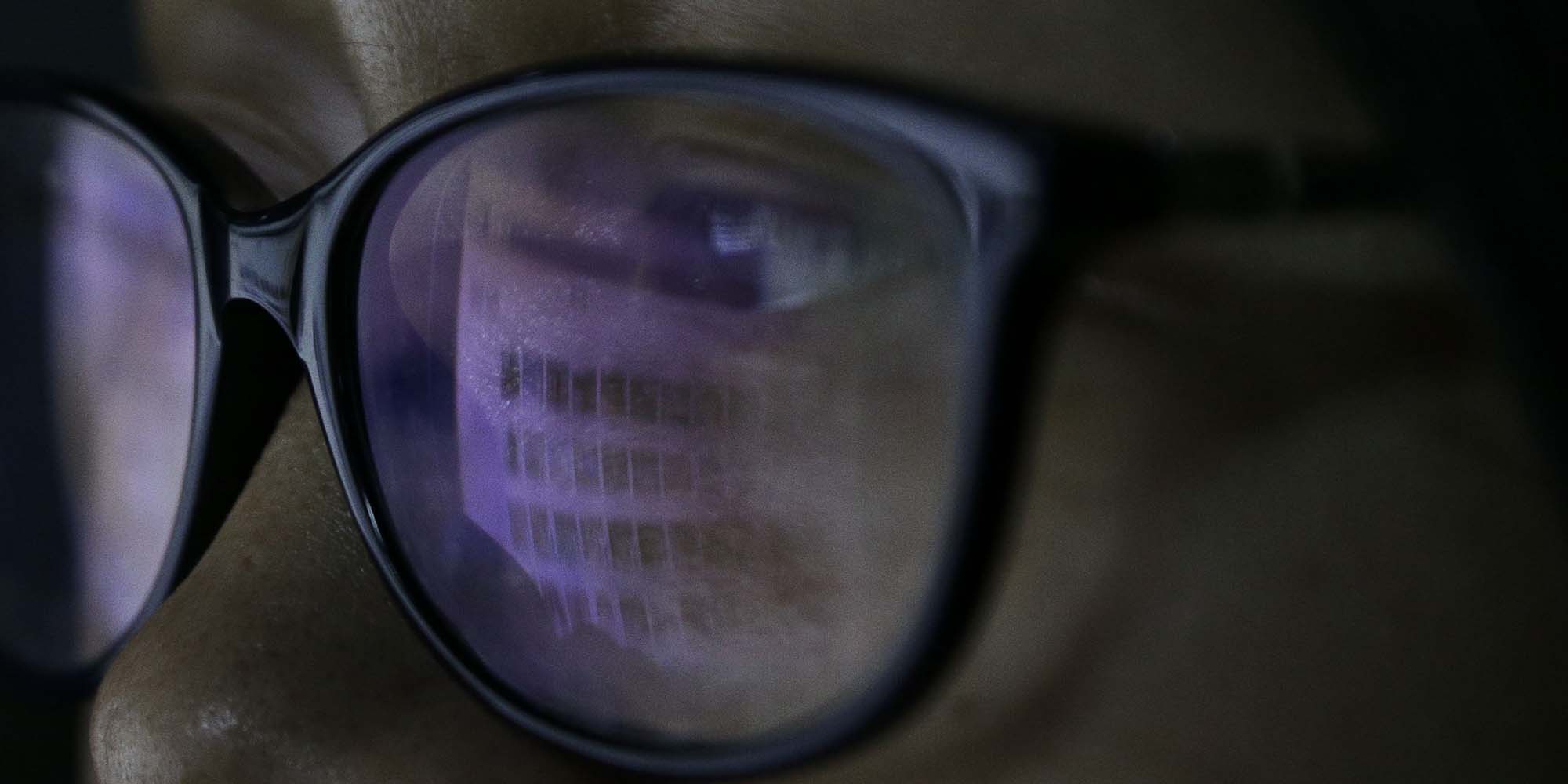

(Header image: Photos are reflected in the glasses of a porn identification officer in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, March 6, 2015. Li Zhanjun/Southern Metropolis Daily/VCG)