The Soundscape of Shanghai

The air of Shanghai is saturated with an immeasurable number of sounds: the braying of street vendors, the pumping anthems of dancing grannies, the ice cream truck jingle of the city sweeper, the rumble of a passing car, the chirping of birds in a park, the wind passing through a narrow alleyway.

Yet rich as it is, Shanghai’s soundscape is largely lost on those who inhabit or visit the city. Like metropolises the world over, Shanghai is best-known for its sights: colonial architecture along the banks of the Huangpu River, the Oriental Pearl Tower, the neon signage of West Nanjing Road, and the labyrinthine longtang lanes of old brick houses.

In June, reporters for the urban research section of Sixth Tone’s sister publication, The Paper, in conjunction with the Shanghai-based Ray Art Center, sought to redress this imbalance. Lasting five months, the “City Roaming” project captured an extensive number of sonic snapshots from around the city, some of which have been repackaged here with original Sixth Tone video footage.

The banks of Shanghai’s Suzhou Creek, a tributary of the Huangpu River, is the perfect place to close your over-stimulated eyes and let the sounds of the city wash over you.

The wail of passing mopeds echoes harshly through the cavernous remains of once-prosperous factories that line the meandering waterway, while the 1946 tango “Along Suzhou Creek” sounds from the speakers of a public museum. Downriver, a blind beggar crosses a bridge as a heartbroken voice croons from a portable music player in his hand. We can hear the clunks of coins falling into his tin, followed by a word of thanks. Men working on the restoration of the area’s old buildings complain that their paint isn’t sticking, as music blares from their cellphones. Perhaps for the superior acoustics, perhaps for the absence of bumbling tourists, an old man has come here to practice the clarinet.

Follow the creek down to the Huangpu River, and you reach The Bund, one of Shanghai’s most symbolic vistas. Today, it is a place that locals rarely visit, more a destination for tourists passing through the city. Among the hurried voices and “Isn’t that beautiful?” mantras of the tour guides, you’ll be hard-pressed to find someone speaking Shanghainese. All the same, “The East Is Red” — ringing out on the bells of the Customs House — screams “Shanghai” to anyone who hears it.

Cross the Huangpu River and enter the depths of Lujiazui’s towering skyscrapers, and you are at once swept up by the rhythm of the financial district. The clattering sounds of the metro station turnstiles clash with the cries of a courier delivering chicken-rice lunches to those with no time to leave the office. The amplified spiels of sightseeing-bus tour guides pierce through the soundscape much more effectively than the shouts of their counterparts on the other side of the river.

Vision may be the most direct and convenient means by which to get to know a city. But it is also easily deceived. In contrast, there is a certain honesty to sound. A city government chasing ecological targets could build a local park overnight, but only once the greenery is accompanied by the sound of birds competing with the surrounding urban soundscape will the space feel real.

It may have its origins in concern for the natural environment, but the study of soundscapes has broadened to encompass the realm of social culture. Within the palette of sounds that populate Shanghai lies a picture of the city’s development — and the human lives it has swept up or left behind.

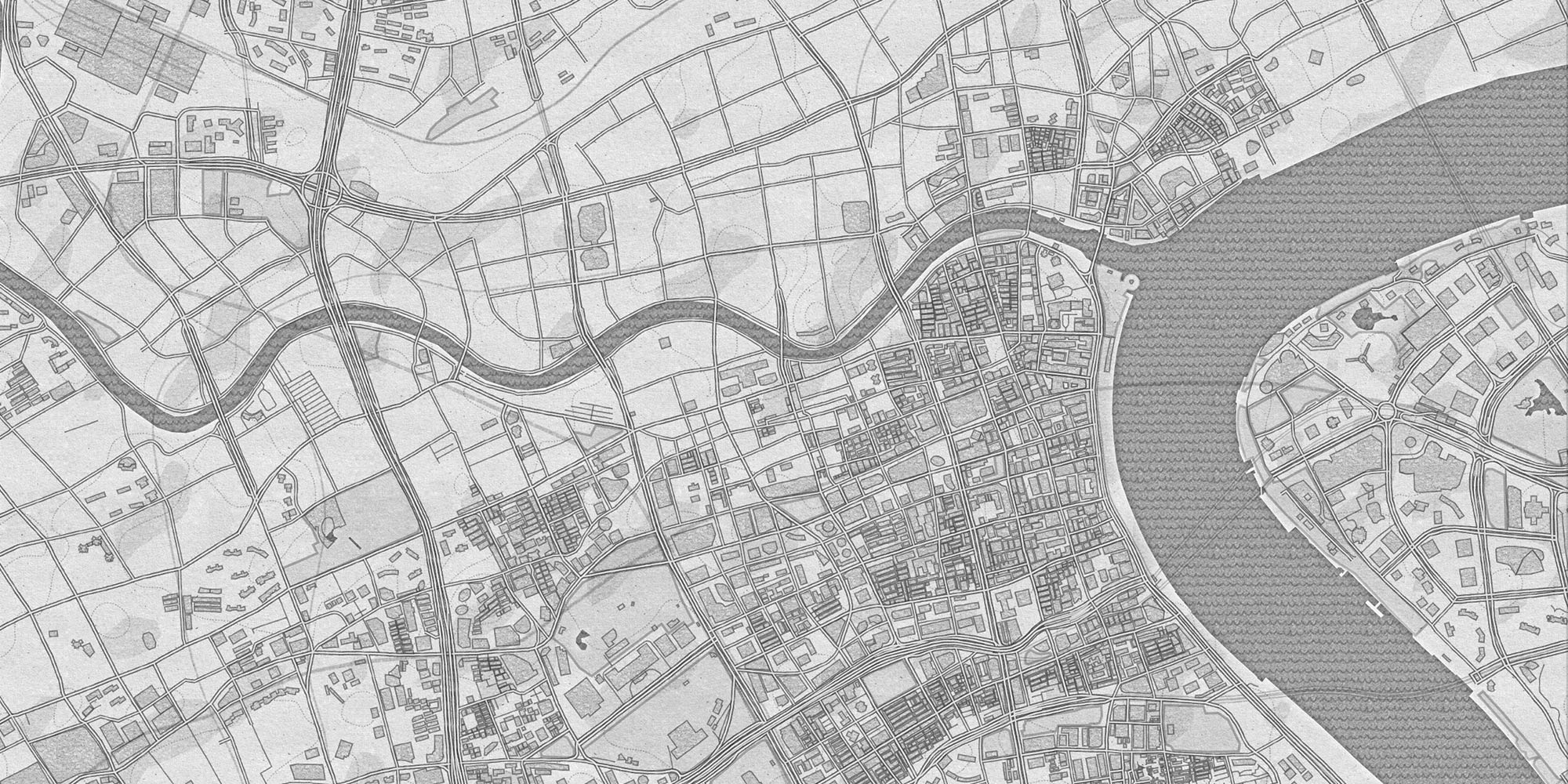

(Header image: A pencil-drawn map of central Shanghai. Mapbox)