Stinky Tofu King’s Business Curdles

For Zhao Baoxian, the day starts at four in the morning in his workshop, where the 55-year-old picks up the large blocks of tofu, or bean curd, that have spent days marinating in his secret recipe and cuts them into small pieces. He then loads the pieces into baskets stacked on the back of his motorcycle and rides to his store 5 kilometers away, just as the city begins to stir.

Shaoxing, in eastern China’s Zhejiang province, is famous for two things: It is the birthplace of Lu Xun, modern China’s most celebrated writer, and it is the home of stinky tofu, one of the country’s most beloved — and most pungent — delicacies. Shaoxing’s biggest tourist attraction is Lu Xun’s former residence, and several small tofu restaurants pepper its surroundings. On a late October morning, the air is cold and smelly.

The touristic center of Shaoxing — now a city of more than 4 million — was once a quintessential Chinese water town, and the white-walled, black-tiled buildings still remind tourists of that past, even if they aren’t necessarily as old as they look. The restaurants they house sell tofu varying in appearance, color, and taste, but their owners all claim to sell the most authentic version of the Shaoxing delicacy. On one thing, however, they all agree: Zhao’s store is definitely the most famous.

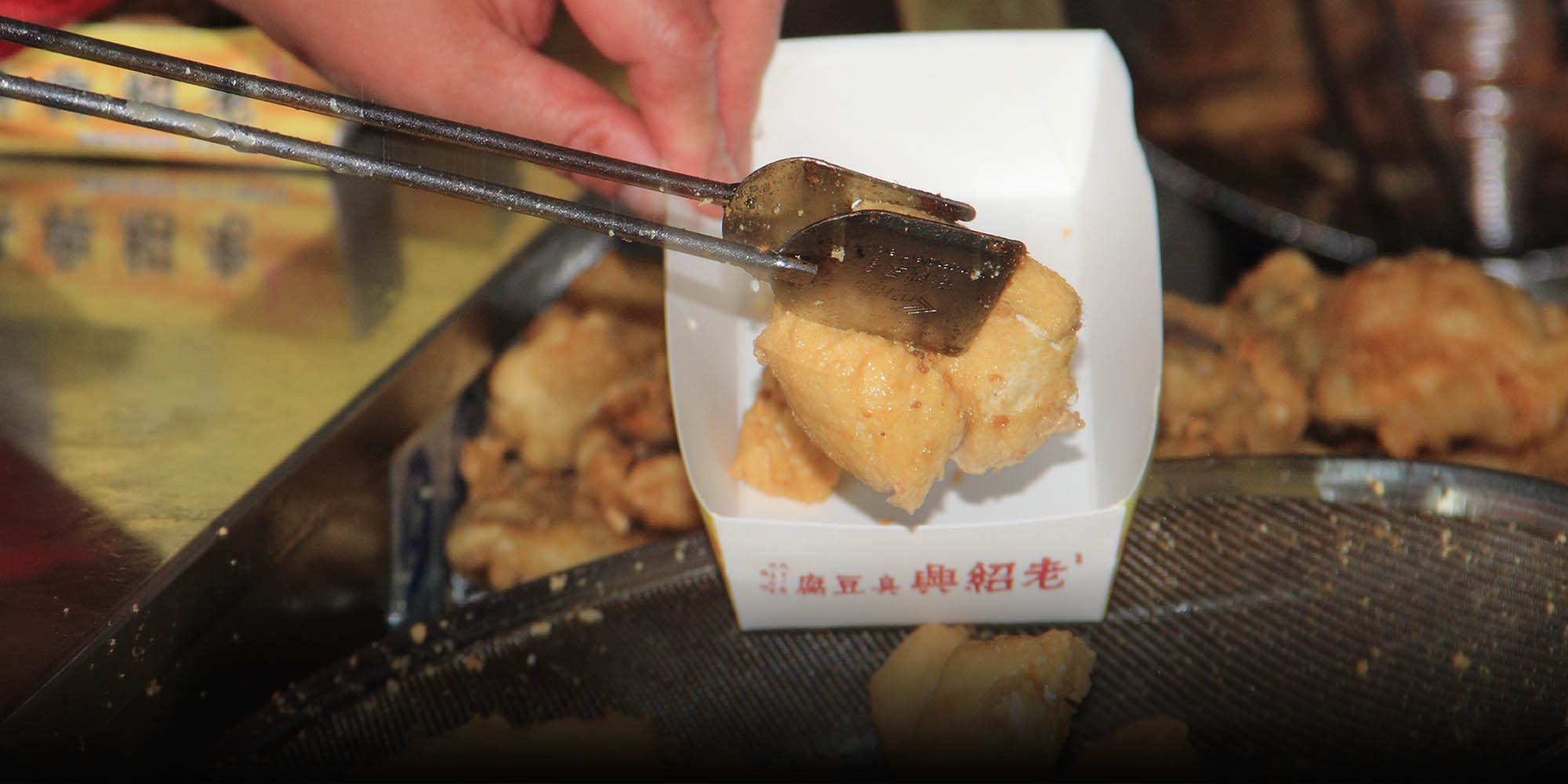

In 2003 the 15-square-meter shop, called “Yuexiang Old Wang,” was the first business to register a trademark for stinky tofu. Old Wang, the original proprietor, is now too old to run the business, and Zhao, his brother-in-law, has been in charge since 2005. Their stinky tofu even has a claim to national fame after its appearance on the wildly popular food documentary series “A Bite of China.”

After three minutes of deep frying, Zhao’s tofu is ready to be served, with a tender core, a crispy crust, and a drizzling of sauces, one sweet and one spicy. Cindy Meng joined the queue and received her 10-yuan ($1.50) serving after a 15-minute wait. “It’s really tasty, and it’s different from the stinky tofu at the other stores,” the 38-year-old tourist from Guangzhou told Sixth Tone.

However, such praise probably doesn’t set Zhao’s mind at ease. Asking his wife to take over the cooking, he steps outside and lights a cigarette. In September, he received a draft notification informing him that the market supervision bureau of Yuecheng District planned to confiscate illegal income to the tune of 87,000 yuan and further impose an administrative penalty of 430,000 yuan.

On March 11, Zhao’s workshop was identified as illegal, as it operates without a license, local media reported Friday. According to the authorities, the tofu made in the workshop is not only served in Zhao’s own store — which he is legally entitled to do — but also ordered by other restaurants — which isn’t allowed. In the absence of a food production and business license, the transaction with other restaurants violates the food safety law, and warrants a fine of five times the value of those transactions. Zhao, for his part, said the fine overstates the money he earned from selling to other restaurants.

Zhao was under the impression that his store’s food distribution license meant his tofu production was within the law, regardless of whom he sold to. The fact that authorities are now forcing him to pay a fine confuses him. “If we were supposed to have a license, why didn’t the related authorities tell me in the past years?” he said. “Instead, when I came to them, I only received the cold-shoulder treatment.”

“I also had a hygiene license valid from 2004 to 2008 for the workshop,” Zhao said, producing the document. He recalled that when he tried to renew the license after its validity ran out, he had difficulties finding the proper department to issue him a new one. “The health department told me to head to the quality supervision department, who then told me they were not in charge of this matter,” Zhao said.

According to the media report, it was not until 2014 that Shaoxing’s municipal market supervision management system was set up, after several departmental changes and mergers. Since then, the authorities have started a campaign to inspect the city’s food-producing workshops.

Local business owners and employees not willing to give their names told Sixth Tone they sympathized with Zhao’s case. The owner of a wine store said that recently, authorities had conducted strict, random inspections. “Basically, they will come to check the license every few days,” he said, adding that though he felt bad for Zhao, he still believed businesses without licenses should be fined.

The cook of a nearby restaurant told Sixth Tone that she felt the size of the penalty was unreasonable. “They should be men of conscience!” the 62-year-old said. “How much stinky tofu would an old man have to sell to pay such a penalty?”

Weng Jianchao, Zhao’s lawyer, told Sixth Tone he is insisting the penalty be canceled. “[Zhao’s] food production hasn’t caused any harm,” he said, adding that issuing the penalty will result in a brand crisis for the stinky tofu industry, and may even cause Shaoxing to lose some of its tradition and fame.

Along the bank of a small, nameless stream, Zhang Jianyu greets tourists with her hoarse voice and a cart carrying two propane tanks and pot of stinky tofu. “Come here! It’s the most authentic Shaoxing stinky tofu!” the 45-year-old hawker shouts to passersby. With her convincing pitch, Zhang says she sells at least 400 servings of stinky tofu every day, though she sometimes has to run from city management officials, or chengguan, who chase her away.

“Three generations of our family have sold tofu,” Zhang told Sixth Tone. Her business started with her grandfather, and she took the reins of the cart from her father 20 years ago. “The tofu is made by me, and even the coriander is planted at my home,” she said, pointing to a white-walled house across the stream.

Near Zhao’s store, a young couple in their 30s run a competing business. With a banner reading “Authentic Shaoxing Stinky Tofu” flying over the roof, the owner, a man surnamed Qi, told Sixth Tone that he came to Shaoxing seven years ago and decided to take over the store from an old lady — “a business opportunity,” he called it.

Zhao’s son, 30, is reluctant to take over his father’s business. “I’ve been making stinky tofu all my life, and I hate the smell when it gets all over my body,” he said. With the possibility of a penalty looming over the business, the son’s resistance to stinky tofu has only grown: He now spends his days baking cakes instead.

(Header image: A worker sells stinky tofu from a food stall in Shaoxing, Zhejiang province, April 30, 2015. Rui Chang/VCG)