Shanghai’s Struggle to Rehabilitate Rehab

Fourteen years ago, Ye Xiong walked out of a rehabilitation center for drug users on the outskirts of Shanghai and made a promise to herself: She would never come back. It was a promise she failed to keep — but this time around she’s back as a volunteer to speak about her past as a drug user. The rehabilitation facility where she spent more than two years of her life as a recovering heroin user now has a new name: the Shanghai Women’s Drug Rehabilitation Center.

In 2008, China’s government enacted laws to tackle the country’s growing drug abuse problems. Instead of sentencing users to periods of punitive manual labor, the legislation insisted compulsory drug rehabilitation should take a more progressive form. “My time there felt more like punishment for what I did,” said Ye, now 59. “For two-thirds of my time there, I was working to produce textile products like towels and blankets.”

In China, drug abuse is on the rise. In 2015, authorities recorded 531,000 new drug users — including those involving drugs that are legalized in other parts of the world, like cannabis — a year-on-year increase of 14.6 percent. A total of 2.34 million Chinese remain addicted to drugs, according to government figures for 2015, although the real numbers are estimated to be four to five times higher, which would bring the total number of drug users across China to at least 10 million. The total number of drug users in Shanghai alone reached 81,269 by the end of last year, a year-on-year increase of 6.2 percent.

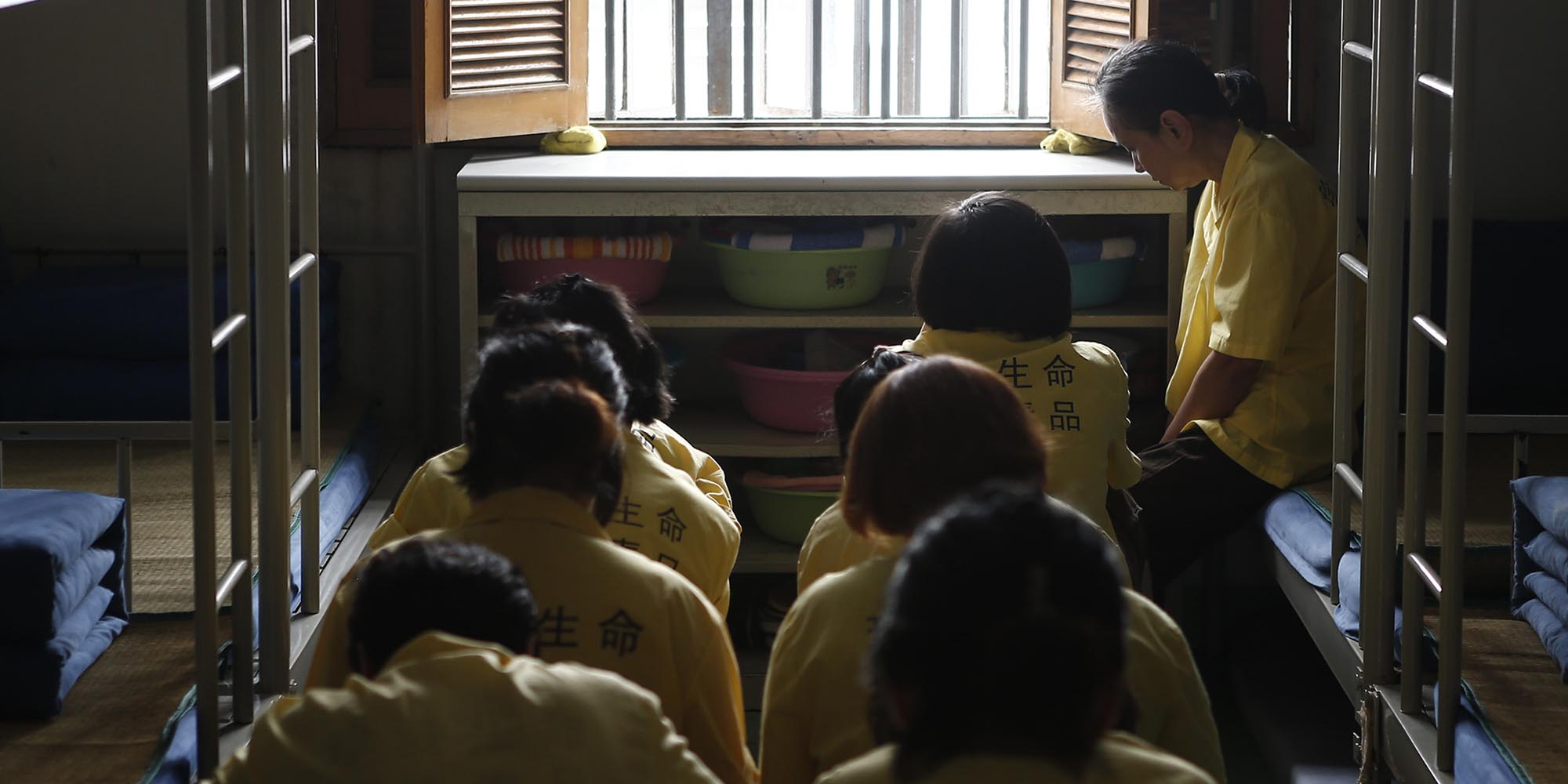

On the surface, the rehabilitation center has not lost its austere veneer. There are iron bars on the windows, and heavy metal doors shut inmates off from the outside world. But Ye still believes conditions have improved, and that the center’s focus is now on recovery, psychological support, and rehabilitation.

When a Sixth Tone reporter and a correspondent for a Dutch newspaper were given a guided tour through Shanghai’s Gaojing Drug Rehabilitation Center for male users they witnessed some of the repeat offenders eagerly exercising with jump ropes. There is a running track, a garden, and a gymnasium. The posters featuring motivational slogans are ubiquitous. “Resist harmful drugs and cherish the beautiful life,” one of them reads.

Most residents at Gaojing have been caught using an illegal substance at least once before. According to China’s “Provisions on Compulsory Isolated Drug Rehabilitation Work by Judicial Administrative Organs,” which went into effect in 2013, on their second offense, drug users spend three to six months in a police-run rehab center before they are transferred to Gaojing to complete their two-year rehabilitation.

Lü Chaohui, head of the Gaojing center, told Sixth Tone they try to integrate elements of tai chi, kung fu, even pop dance in the everyday physical exercises. “These methods were developed by our center, in cooperation with domestic hospitals and universities,” he explained, adding that 45 psychologists are currently on staff.

However, international civil rights organizations have criticized China’s approach to state-mandated drug rehabilitation, arguing that drug users should be treated as patients, and should not face compulsory detention without a trial.

According to the Gaojing center, 73 percent of former users relapse within the first 3 to 5 years after their release. In the U.S., for example, the average relapse rate recorded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2000 was between 40 and 60 percent. However, individual city rehab clinics in America regularly report much higher relapse figures.

Wang Xieying, a social worker from Changning District in Shanghai, told Sixth Tone that a drug user is considered to have had a successful recovery if they are able to submit clean urine samples for three years after being released from a treatment facility.

In 2012, the United Nations called for all compulsory drug rehabilitation centers across Asia to be shut down, saying not only that they were a human rights concern, as those detained were not granted due process, but also that there was “no evidence that these centers represent a favorable or effective environment for the treatment of drug dependence,” according to the joint statement.

In Shanghai, there have been tangible efforts to introduce community support to prevent drug users from relapsing.

In 2003, Ye became one of the country’s first community-based social workers dedicated to helping drug users. She had seen that people who were released from the center were offered no support and, not surprisingly, quickly relapsed. One man relapsed nine times, she said, and ended up spending around two decades of his life inside rehab facilities.

“The ultimate recovery of any user can only happen after they have been integrated back into society — that’s why community-based services are so crucially important,” said Ye, who is now one of around 1,000 social workers who help drug abusers. She also founded Sea Star, an organization comprised of 26 former drug users who now share their stories of addiction and recovery with others. “Many drug users assume they can never get off drugs for the rest of their lives, once addiction has taken root,” Ye said. “People like me are powerful examples — our experiences tell them it’s not ‘Mission: Impossible.’”

For Yu Shengren, whose name has been changed to protect his identity, the introduction of 40 social workers to his local district has changed the course of his recovery. A heroin user since 1995, Yu has spent more than six years at three different compulsory rehabilitation centers in and around Shanghai. He says that working with social workers and volunteers gave him a valuable support network.

“I thought of it as a self-fulfilling prophecy: that if everybody looked at me as a hopeless drug user, then that’s exactly what I would be,” he said. Stigmatized and treated as an outcast, even by his own family, Yu relapsed every time he left a treatment center. But the third time around, things at the center had changed.

Volunteers, whose titles can be literally translated as “anti-drug mommies,” were on hand, and they visited the center regularly. These retirees support the city’s social workers and establish relationships with users inside the facility that continue after the inmates are released. “She contacts me frequently, and we basically just talk about everyday life,” Yu said, referring to Zhang Mei, a retired woman in her 60s who served as his anti-drug mommy.

“We have to ensure that users’ contact with any drug-using friends is cut off,” said Zhu Weishui, director of Changning District’s drug control office, which employs 40 full-time social workers.

Xiao Xu, a 32-year-old sales manager at a local pharmaceutical company, told Sixth Tone that he tried, and failed, to quit drugs on his own. As a postgraduate of a medical school, Xu was aware of the damage drugs could do when he first took meth in 2013. But on meth he was able to play mahjong all night long, without ever feeling tired. Besides, he said, it helped boost his sex drive.

When Xu turned to his mother for help, the first option she found for treatment was a compulsory rehab center in their hometown in Zhejiang province. She rang the center, but the center’s own staff told her that her son shouldn’t go there. Only people caught by police ended up there, she was told, and on top of the two-year mandatory stay, her son would have a criminal record, making it difficult for him to find employment afterward. The better alternative, she was told, would be a voluntary, private treatment center, where patients’ privacy is protected. In 2010, there were 141 voluntary drug rehab centers across the country, according to the most recent available figures from the Ministry of Health.

Shanghai Sunshine Drug Relapse Prevention Medical Center is one of only a handful of centers in the metropolis. Established in 1998, the center told Sixth Tone that it had received more than 3,000 families.

While the government only funds compulsory centers, Qin Hongming, the founder of Sunshine Center, which promotes family-centered therapies, believes that voluntary drug rehab centers might be more successful. “The full recovery of a former drug user can only be realized when their families understand their conditions well enough and know how to support them,” Qin said.

In June, Xu started therapy sessions at the Sunshine Center. “Drugs have basically ruined my life,” he said. “I couldn’t focus on anything, and I lost interest in everything. I had to ask for leave from work because I couldn’t function.” For the first month of his therapy, Xu spent most of the time at home under the watch of his mother, going through physical detox and the accompanying withdrawal symptoms. But just as important as kicking the habit is teaching drug users how to go back to a life they last navigated while under the influence of drugs, and in which they are still known as drug users. Qin’s staff of eight physicians and psychologists spent a large amount of their time speaking to patients’ families.

“We are unable to alter the wider social environment, but we can optimize the environment in these individual families. The understanding and care from the people closest to them can fortify the patients’ determination,” said Qin, adding that according to the center’s own figures, close to 80 percent of patients stay clean for a year or longer.

Xu returned to work during the second month of his treatment. At the bus stop, he remembered the deals he made to buy meth. Online, his drug user friends would contact him. Xu struggled to stay clean. “Fortunately, professionals at the center had warned me beforehand and provided some solutions,” he said.

Thinking about taking drugs again was part of recovery, Xu had been told, and this didn’t mean that he had already failed in abstaining. For a year of treatment, Xu paid 50,000 yuan ($7,500). But he said he knows one year is not enough. “I believe abstaining from drugs will be a lifelong task for me,” he said, “and there’s no shortcut to achieving that.”

Additional reporting from Fu Danni.

(Header image: Drug users detained at a compulsory rehabilitation center gather in their dormitory in Shanghai, June 24, 2013. Yang Yi/Sixth Tone)