Rote Learning School Leaves Bad Memories

As a young teenager, Dong Ruoqi was able to recite the Bible as well as Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” all in English. She didn’t understand a single word, however, and wouldn’t have been able to introduce herself in the foreign language.

Apart from English classics, Dong, now 19, had also memorized Confucius’ ancient teachings and some Buddhist scripts, and even though those texts were written in Mandarin, her native language, she failed to grasp their meaning and never had them explained to her. “I was very depressed at that time. I thought about committing suicide,” Dong said with tears in her eyes.

Dong spent most of her teenage years in a small private school that had adopted the educational doctrine of Wang Caigui, a former philosophy professor at Taiwan’s National Central University who started a widely popular trend in education that came to be known as “Reciting Classics.” He rejected the national education system and 20 years ago started to tour the country giving passionate public speeches on education.

Young students, Wang argued, aren’t capable of understanding the meaning of texts and should not bother learning algebra or science. Instead, the key to a solid foundation for a child’s future lies in the memorization of classic works of literature. Interpreting and understanding these texts should not just be neglected, but forbidden outright until the age of 13.

Wang’s speeches have since been burned onto hundreds of thousands of DVDs and transferred onto USB sticks. Online, millions have seen him speak.

“Reading the classics is more useful than studying the useless content taught in our current education system,” Wang, who is now 67 years old, told Sixth Tone.

Frustrated with the stringent and highly competitive school system they knew from their youth, thousands of parents saw Wang’s approach as an alternative with potential. The rigid, exam-oriented education system that pinnacles in the gaokao, China’s notorious college entry exam, had robbed them of their own childhoods. Their children, they reasoned, shouldn’t have to suffer the same fate.

Middle-class parents like Dong’s mother have become some of the strongest critics of China’s education system, and more and more of them are opting out. Last year, consulting firm McKinsey & Company found that a total of 12,000 secondary schools — 10 percent of all secondary schools in China — are privately run, up 3 percent from 10 years prior.

For Dong and her mother, Reciting Classics was a way out. The new school, they believed, would make children happier and more fulfilled.

At first, the new school seemed like a walk in the park for the hardworking teen. Although she had to memorize texts from 6:30 every day, morning to evening, there was no homework or extracurricular activities.

Soon, however, Dong started to become critical of her teachers. “The texts I had memorized were just meaningless words,” she said. “In addition, all I knew was the world inside that campus. I didn’t know how to apply the texts in the real world.”

Dong developed into a confused, angry teen. The other students were having trouble as well — some even resorted to self-harm. Their teachers, meanwhile, were ill-equipped to help. Some Reciting Classics schools have as few as two students, while larger ones have as many as 200. Most teachers are parents who had no previous experience or training as teachers. But for Wang’s theory, that poses no concern, because all teachers need to do is read classics with the children, again and again, without any lecturing or any understanding of the teaching materials.

Although Dong grew increasingly frustrated over the reams of texts she had to memorize without ever questioning their meaning, her mother believed it was her daughter’s problem and wanted her child to remain in the fold. “I believed that [as parents] we should obey the rules of the school and the teachers’ classroom management,” Dong’s mother told Sixth Tone.

A parent who did not want to be named out of concern for her daughter’s well-being said that corporal punishment was the norm at some Reciting Classics schools. At her daughter’s school, children were required to read out loud, almost shouting. Those who did not read loudly enough would be beaten with a bamboo stick or wooden ruler.

Some schools even pointed out their strict education policies in their admissions requirements, explicitly stating that they used corporal punishment. But some parents are happy that their children are being strictly educated at the schools, believing that this approach can change bad habits.

Wang admitted that some teachers use corporal punishment to push students to study. “If they study hard, they will be changed by the classics, and their bad habits will go away,” Wang said. He defended the discipline policy by arguing that strict education could cultivate great talent, and thus should not be criticized so harshly.

Ke Xiaogang, a philosophy professor at Tongji University in Shanghai, told Sixth Tone that China’s current education system is pushing parents towards alternative paths, including Reciting Classics. Though parents seem to care a great deal for their children, Ke said, many know very little about what is really happening inside these alternative schools, and some are in fact irresponsible for letting schools take full control of their children’s education.

Years after the Reciting Classics schools opened, the first students who spent the majority of their school years in such traditional private schools are openly criticizing the system. They say that they face an uncertain and confusing future, making their parents question whether they chose the right path.

In an open letter to a professor at Shanghai’s Tongji University, Zheng Weisheng, who attended Reciting Classics schools from ages 10 to 18, wrote: “Reciting Classics has become more and more popular over the years, and there are more and more students like me. I embarked on this path early, but now, when I think about my future, I feel confused. Many of my classmates feel as anxious as I do.”

Zheng told Sixth Tone that he changed schools several times, from one remote mountain region to the next. Seclusion is key to the Reciting Classics education, as the outside world offers too many distractions from study. One of Zheng’s schools was staffed by a single teacher who oversaw a total of three students — and seven dogs. Whenever it rained or snowed, the electricity was cut off.

After eight years of memorizing classic texts from early morning until late at night, Zheng said he doesn’t know how to find a place in society. Going back to public school and taking the gaokao isn’t an option — “I have been gone for too long,” he said.

In hindsight, Zheng realizes that the system offered no long-term plan for his future. The only prospect the students ever had was getting accepted into Wenli School, which claims to be the Harvard of traditional Chinese private schools, in China’s eastern Zhejiang province.

From the closest town, Taishun, a total of 11 tunnels lead deep into the mountains where Wenli School is located. “We have been to many places in search of an ideal location, and at last we found this place,” said Cai Mengcao, a teacher at Wenli School, “It is the perfect place for our students to study, as it is isolated from the outside world.”

Once students enroll at the 30,000 yuan-per-year school ($4,500), they finally get to interpret the texts they have been reciting and memorizing for years. The entrance requirement, however, is somewhat bizarre: Students have to submit videos of themselves reciting 300,000 characters of classic text, without pausing, stuttering, or making a single mistake. Videos of up to 2 hours in length of students trying to fulfill the requirement have been posted online. Thousands of students compete each year for spots at Wenli School, rattling off the writings of Confucius or Lao–tzu without any emotion.

Huang Yulin, 25, is one of 33 students currently studying at Wenli School. He said he is happy that the meaning of the classics is finally being revealed.

Wang, who heads the school, believes that this type of education will bring forth the next Confucius-like sage. “Even if you cannot become a sage, you are heading toward the best possible outcome,” Wang told Sixth Tone. He still deeply believes in his teachings, and said that reciting classics is the only thing that can ensure a child’s future success.

Zheng, the student-turned-critic, disagrees. After attending Reciting Classics, he says his future remains uncertain. He is interested in studying international politics, but without a proper high school education, such a degree seems out of reach. One of his former schoolmates went to a university by passing a special entrance exam for talented calligraphers, but others are working low-skilled jobs or playing computer games all day long.

Now 19 years old, Zheng spent the last year trying to prepare for a college entrance exam for self-taught students. He regrets having ever attended Reciting Classics schools, or at the very least that he did not leave them sooner.

“Sometimes,” he said, “giving up is more difficult than carrying on.”

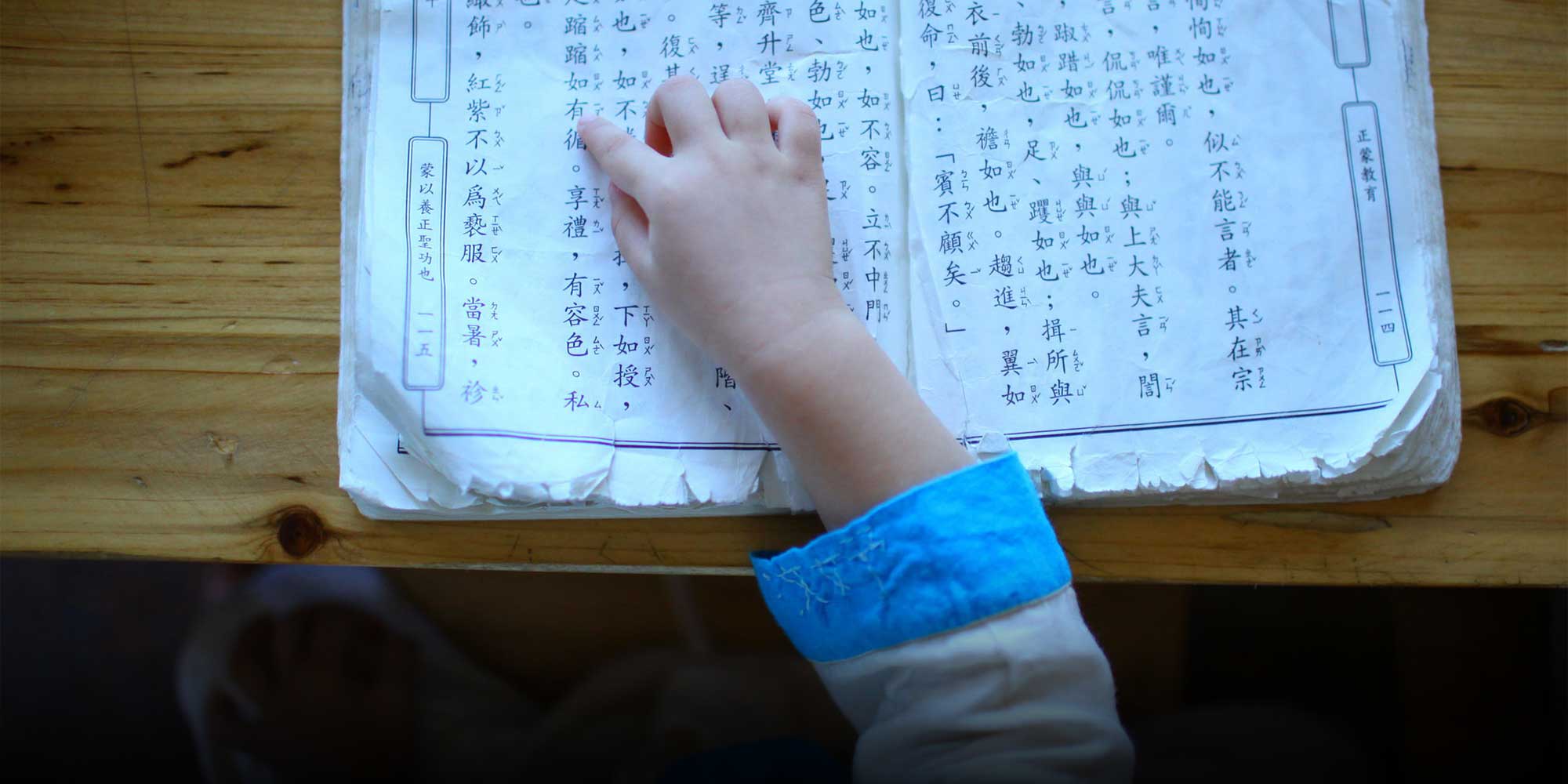

(Header image: A student points to a character in a tattered textbook at a Confucian private school in Haikou, Hainan province, Aug. 25, 2011. Mi Ke/VCG)