Video Start-Ups Seek to Break Free of Rigid Sports System

“Shoot!” A young boy, the son of a member of China’s national football team, kicks a ball and it hits the camera. He laughs, other people in the room laugh, and the video ends.

The nine-second video was posted to Miaohi, a new Vine-like video app that’s betting its future on short, intimate, behind-the-scenes moments of the lives of Chinese athletes. Miaohi is one of many startups that are trying to capitalize on sports celebrities and the popularity of short videos — what should be a recipe for success if it weren’t for the strict regulation on investment in the sports industry.

“China’s sports businesses are now at the 30th minute of a football match,” said Li Sheng, chief operating officer of Haiqiu, the 60-strong internet tech company behind Miaohi. From the company’s offices, located in the Zaha Hadid-designed Galaxy SOHO building to the east of Beijing’s city center, the 41-year-old former sports journalist expanded on his metaphor: Just as players use the beginning of a game to adjust their strategy in response to the competition, Haiqiu is tentatively finding its way as an increasing number of sports-based internet startups enter the fray.

Haiqiu was founded in February of this year by Sun Jihai, a footballer formerly with Manchester City Football Club who now plays in China’s second division, China League One. With an array of contracted A-list celebrity sports figures, including runners, footballers, and Olympic swimmers, the company wishes to build up an online community between fans and sports professionals that challenges conventional representations of sports stars in mainstream media.

Along the way, of course, they might make a buck or two. Following the ongoing decentralization of China’s sports infrastructure, related industries are finding themselves flush with investor money.

In May this year, China’s General Administration of Sport vowed that the value of the country’s sports industry would grow to more than 3 trillion yuan (about $450 billion) in 2020. In 2014, the year for which the most recent statistics are available, that figure stood at around 1.4 trillion yuan.

While regular users are free to sign up and share their own video content, the platform’s selling point is the more than 300 athletes who use the app to share snapshots of their lives in several-second bursts. Of those, some have entered into contractual relationships with Miaohi, the terms of which Li Sheng declined to elaborate on.

The app was launched in June, right before the Olympic Games that are currently underway. Many of Miaohi’s most watched videos show a side to the athletes’ lives in Rio that — albeit mundane — rarely makes it to mainstream coverage of the games.

Fencer Sun Wei, who was knocked out in the first round, tells the camera he is sad to leave the Olympics but is looking forward to eating some nice food back home. Swimmer Liu Xiang, yet to compete, tells her watchers it is currently 8:30 in the evening and that she has finished training. A pout of the lips and a cheeky smile fill up the rest of the short video.

The pull of sportspeople sharing their non-sporting moments on social media became particularly apparent this week when Olympic swimmer and meme-machine Fu Yuanhui — loved for her expressive and offbeat interview manner — attracted more than 10 million viewers and 320,000 yuan in virtual gifts during a broadcast on live-streaming app Ingkee, in which she answered questions and ate cupcakes.

Miaohi and Ingkee are not alone in capitalizing on sky-high interest in the sports industry and the increasing popularity of video-based social media platforms.

In the opposite corner of the Chinese capital, nestled in “China’s Silicon Valley” Zhongguancun, a company called Starchat is also attempting to bridge sports fever with mobile users’ increasing penchant for digestible video content. Beginning as a sports-based live-streaming service in April this year, the app now hosts recorded videos similar to Miaohi’s.

Li Xiaoning, CEO of Starchat and of no relation to Miaohi’s Li Sheng, believes the first-person perspective videos made by athletes provide a valuable antidote to the narrative of state media and its tendency to glorify the country’s athletes to an extent that normal people struggle to identify with them.

“We want to present the 10 seconds of the athletes before the match instead of the moments of glory broadcast by state television,” said 43-year-old Li. “We want to build a channel for sportspeople and fans where they can communicate directly.”

For viewers, that communication means either posting comments, which the athlete may choose to respond to, or sending virtual gifts that are purchased in-app with real money. A virtual airplane, for example, will set you back 500 yuan, while a simple Band-Aid will cost you 0.1 yuan.

Li sees this as a valuable stream of revenue for the young startup. But like Miaohi, Starchat also has its eyes on advertisements and sponsorships — product placement — to make money.

Li hopes that the platform’s star lineup will be a big pull for investors. But the relationship between China’s sports stars and endorsement is not without hurdles. Individual sportspeople competing for the country are bound to a team, and that affiliation frequently means being ascribed to fixed, state-sanctioned choice of sponsor.

Olympic swimmer Ning Zetao reportedly came close to missing his spot on the Chinese Olympic roster this year after he featured in an advert for dairy goliath Yili, a rival of the team’s official endorser Mengniu.

The issue rose again to prominence this week when viral swimmer Fu Yuanhui posted a photo on her Weibo microblog depicting her holding a bottle of mineral water, replete with a watermark of the water brand. Just a little over an hour later, she followed with a post in which she bemoaned her obligations as a national athlete to her team. “I didn’t want to go down the route of commercialization,” she wrote, before going on to blame her fans. “If it weren’t for you I wouldn’t have to post adverts.”

It’s a minefield that Li Sheng of Haiqiu is well aware of, likening the restrictions on sports stars’ financial development to a “bottleneck.” “There is a conflict between the commercialization of sporting celebrities and the state system,” he said. “Financial profit for these professional players is not necessarily in their own hands. Sporting management bodies and the General Administration of Sports also have a say.”

Miaohi’s approach, Li said, will be to cooperate wherever possible with the country’s sporting bodies, pointing to grassroots sports industries as an example. “The football training youth system and other public sports events are controlled by the authorities,” he said. “If we want to penetrate that area, I think contact and cooperation with the relevant departments are necessary.”

Starchat’s Li Xiaoning, on the other hand, thinks that too much contact with the authorities could be toxic for a young startup. “The cost to negotiating with the authorities is too high for startups,” he said, alluding not to a financial cost but restrictions on the freedoms of the platform to communicate directly and independently with its star athletes.

Starchat will avoid any in-depth communication with the authorities, Li said, but will nevertheless avoid crossing any red lines. Though that might mean losing out on financial gain, he said the priority now was not to amass money or gain resources but to ensure the existence of a platform on which athletes can maintain a personal degree of interaction with fans.

But this is new ground, and even Li has his own reservations about his strategy of choice, especially given the increasingly crowded competition. “For startups, you never know if you are running a 400- or 3,000-meter race,” he said.

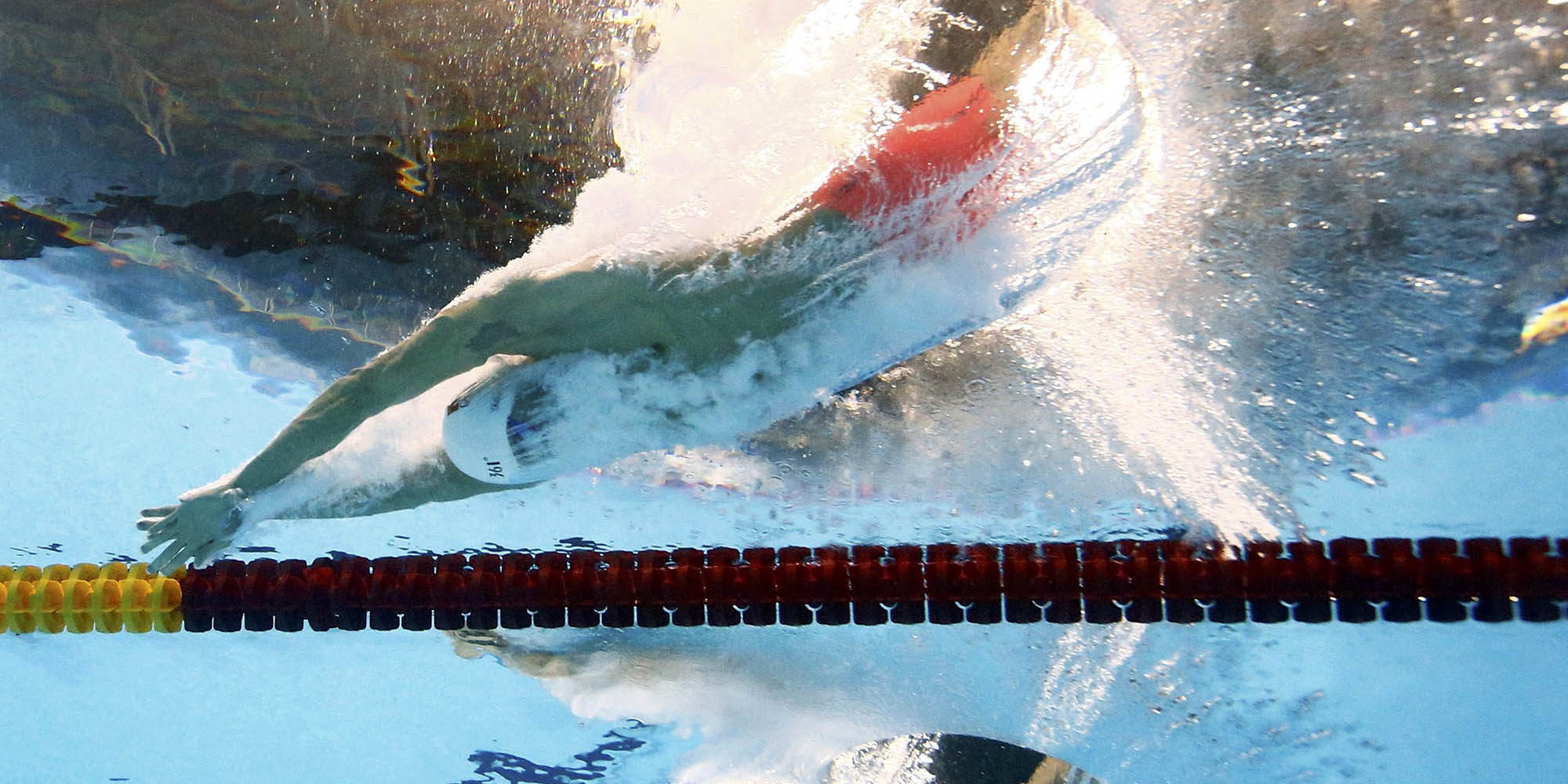

(Header image: Swimmer Sun Yang competes in the men’s 200-meter freestyle at the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Aug. 7, 2016. Michael Dalder/Reuters)