Drinkers Draw Together to Dry Out

In a small rented room in Shanghai, Sun Wu, 40, announces to those seated: “My surname is Sun. I’m an alcoholic. I’ve been sober for five years and seven months.” His words win applause and respect from the five others present because he’s the veteran teetotaler of the group, as well as the meeting’s organizer.

No one in the room knows each other’s real names, ages, birthplaces, or anything else about their daily lives. All that they have in common is their experience with alcohol abuse and dependence, and their will to quit drinking. “An alcoholic can be anyone — a lawyer, a scriptwriter, a teacher,” Sun tells Sixth Tone. “You can’t tell from their appearance, but it’s a serious illness.”

Though the prevalence of alcohol dependence in China is not as high as in other countries — 2.4 percent in 2010, according to the WHO, compared to 4.7 percent in the U.S. — the size of China’s population means that there are 2.3 times as many people affected by the illness as in the U.S.

Alcohol consumption is also growing. According to a study in The Lancet, although China has a high proportion of alcohol abstainers — 71 percent of women and 42 percent of men, in 2010 — the country has also seen a substantial rise in drinking over the last few decades. Per capita alcohol consumption rose from 4.9 liters from 2003 to 2005, to 6.7 liters from 2008 to 2010. But while several policies aim to reduce smoking in China, lawmakers and media give little attention to alcohol.

“I was born an alcoholic,” Sun says. He’s been hooked since his first taste of alcohol, when he was in eighth grade. China has no laws stopping minors from purchasing alcohol and no rules mandating health warnings on liquor labels. In 1994, before their high school entrance exam, Sun and his friends decided to commemorate their brotherhood by dripping their blood into a bowl of baijiu — a potent clear spirit, distilled from grain — paying homage to the kung fu stories that they revered.

Sun downed the bowl of liquor in one gulp. He then went on an alcohol-fueled rampage through the classrooms, toppling desks and smashing windows. The police caught him and fined him 300 yuan ($45), and his school expelled him without a diploma.

With no real ambition or direction, Sun started drinking more, relying on a bottle of baijiu a day to keep him going. According to the 10th and current edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), alcohol dependence refers to a chronic disorder “characterized by a pathological pattern of alcohol use that causes a serious impairment in social or occupational functioning.” To his boss, Sun was a troublemaker who not only drank all the time, but also became irritable and violent toward his colleagues when drunk. “I’m an asshole,” Sun confesses. “For more than 10 years, my life shuttled back and forth between finding a job and getting fired, all because of alcohol.”

The rift between Sun and his family grew deeper. None of them realized that he was suffering from an illness; they just blamed him for being irresponsible. When Sun’s wife was giving birth to their only child on June 19, 2004, doctors and nurses at Shanghai Songjiang Sijing Hospital searched everywhere for him. Eventually they found him, blackout drunk, at a temple in the hospital’s backyard, surrounded by empty bottles and completely oblivious to the fact that he had just become a father.

It wasn’t until 2009 that Sun’s parents realized the seriousness of his alcohol dependence. Their solution was to lock him in a room. Sun was isolated, terrified, and in unbearable pain. He experienced vomiting, seizures, tremors, and nightmares every night. “I saw the gods, the demons. I even saw evil people trying to kill me and chop me with a sword,” he recalls.

According to Huang Jian, an expert in alcohol-related diseases at Peking University Sixth Hospital, one of the country’s best mental health hospitals, such symptoms suggest the most severe form of withdrawal, which can be life-threatening if medical assistance isn’t given. Li Bing, director of clinical psychology at Peking Sixth, worries that most people don’t seek medical advice when trying to quit drinking. In rural areas, people will even favor superstitious methods, such as drinking homemade eel and carp liquor, or performing Taoist exorcisms involving tea made from the ashes of paper talismans.

What causes the problem is a lack of both public understanding and official regulation on alcoholism. Li says even the health ministry isn’t paying much attention to the harm of alcohol. Although China has well-developed policies and controls on drunk driving, there are few restrictions on the advertising, sale, and purchase of liquor. The health ministry did not immediately respond to a request for comment from Sixth Tone on Friday.

In the most recent version of the Chinese dietary guidelines published on May 13, 2016, the health ministry suggests that the daily intake of pure alcohol for adults should be no more than 25 grams for males and 15 grams for females. But doctors say these guidelines have no real impact on the public because they don’t appear on labels or in places where liquor is sold.

Drinking is an important feature of many Chinese social gatherings, and strong liquor such as baijiu plays an especially integral part. While alcohol dependence can impact anyone, Chinese men are 45 times more likely to be alcohol-dependent than women, according to WHO figures from 2010. The perception of a man as brave and courageous can depend on how much he can drink, and drinking toast after toast with one’s superiors is often a path to promotion. Sun admits that while he revels in the feeling of being drunk, what really pushes him to drink more and more is his peers’ applause and encouragement.

Social pressure and psychological barriers can be as significant as the physical symptoms of withdrawal. Even when someone acknowledges the harm alcohol is doing in their life, alcoholism expert Huang says they will often still find reasons to drink, whether it’s social pressures or the demands of work. Although some may be able to outlast the period of withdrawal reactions, they still struggle with the psychological addiction.

Few consider alcohol dependence to be an illness that requires medical attention. “Chinese people realize that drinking liquor will have an impact on their health, but they don’t understand that it can transition into dependence,” Huang says. Li says that most of the patients she sees are older, and after decades of serious drinking, they have little chance of overcoming their dependence. In such cases, she and the other doctors are limited to treating the physical issues caused by long-term alcohol abuse.

As a doctor, Li is always trying to find more effective ways to help her patients. In 2000, she got in touch with Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) in Minneapolis. She decided to introduce the program in China and invited her patients to attend the first meeting at her hospital.

Although AA has a long history internationally since its establishment in the U.S. in 1935, the program has confronted difficulties in strongly secular China. Atheist patients are skeptical toward the religious undertones of the 12-step program: seven of the steps mention God, “a Power greater than ourselves,” or a “spiritual awakening.” One woman, whose brother became addicted to alcohol while working for a beer manufacturer, tells Sixth Tone she hasn’t succeeded in persuading her brother to attend AA meetings because he’s reluctant to join what he sees as a religious group.

The overall concept of support groups also isn’t very familiar or popular in China. “Chinese believe that treating an illness is a doctor’s job, that it should be cured by medicine,” Huang says. “They don’t think talking to each other can help solve the problem.” But despite patients’ doubts, Li is persistent and confident when it comes to the AA method.

Currently, there are four AA events each week in Beijing, and patients hold the events themselves outside the hospitals. AA has set up local branches in other cities, too. In 2010, one member surnamed Dai gave a speech at a mental health center in Xuzhou, in the eastern province of Jiangsu. The doctor there told Sun he should consider attending. After drinking heavily for nearly 20 years, Sun had no career, no savings, and was on the edge of divorce. He decided he had nothing to lose.

Sun still remembers his excitement when he heard that the first step was to admit defeat. It reminded him of his crushed dream of becoming a martial arts coach. He decided to move to Shanghai to focus on attending meetings regularly and trying to save his marriage.

But while the AA group in Beijing enjoys hospital support, in Shanghai the hospitals and government were uninterested. Sun and another member, Cai Liangyi, are trying to recruit doctors to support their cause. Cai says, “If doctors recommend AA, we can expand our influence.” He hopes to find a hospital that will agree to host meetings and allow AA to speak to patients, as happens in other cities.

In the meantime, Sun’s enthusiasm is driving the group’s development. He pays out of pocket to print materials, and he’s created a forum on MSN-like communication tool QQ. His group now has more than 1,700 members.

All names of Alcoholics Anonymous members are pseudonyms.

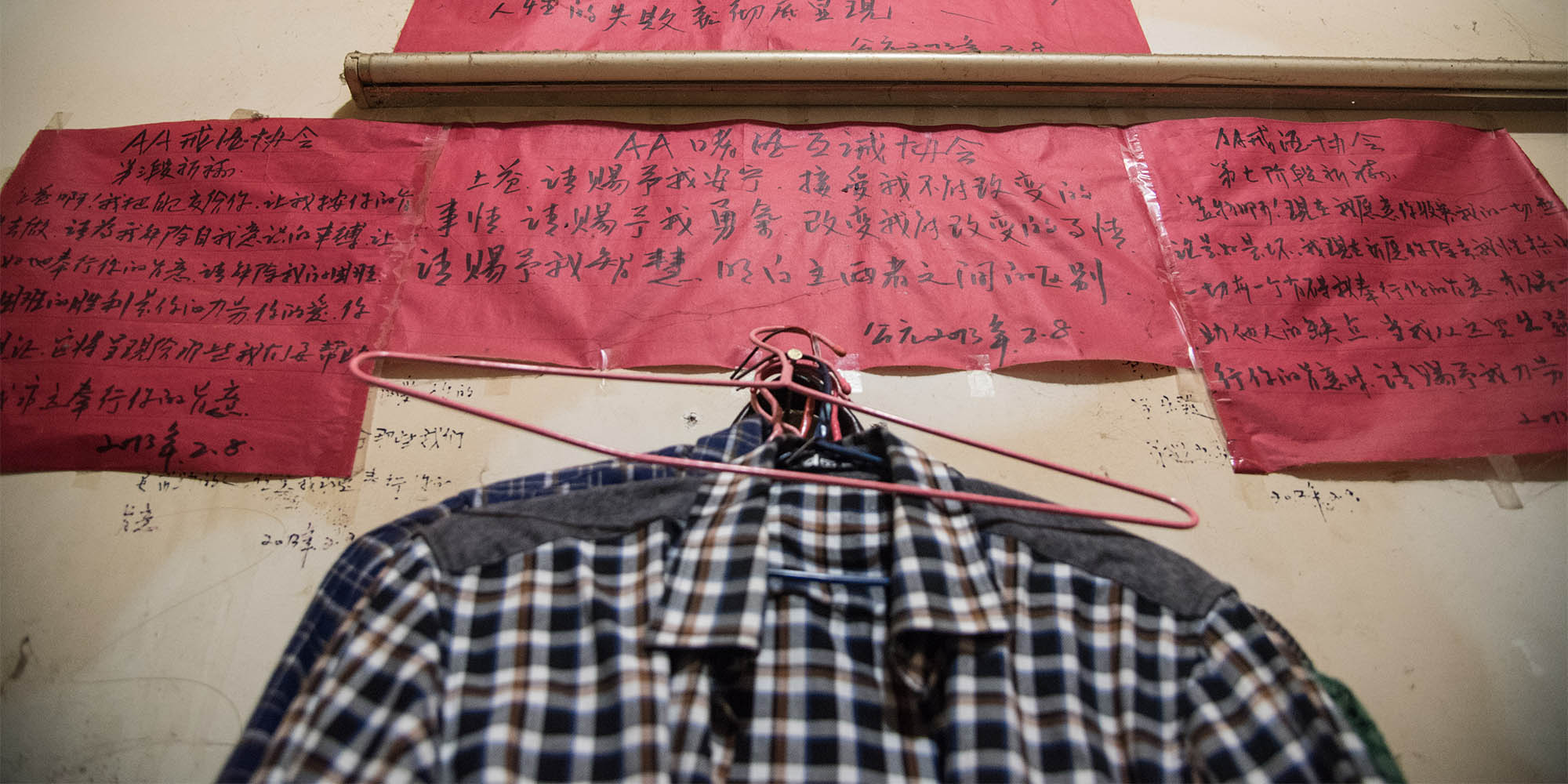

(Header image: Core doctrines of Alcoholics Anonymous are displayed on handwritten posters on the wall of Sun Wu’s home, Shanghai, June 29, 2016. Zhou Yinan/Sixth Tone)