Crammer vs. Crammer: Notes from a Civil Service Crash Course

Editor's note: Getting through the national civil service exam in China is often described as “going ashore” — one leaves behind the volatile “sea” and sets foot onto stable “land.” In 2021, over 1.5 million people registered for the exam. Of them, approximately one in 61 will get through.

It’s not just fresh graduates who are attracted to the civil services. Most people employed “outside the system” — non-public sector workers — fill coaching classes every evening hoping to secure a government job. Many refer to such jobs as “iron rice bowls” for the financial security they provide, and hope to pass the exam before they hit the age ceiling of 35.

Liu Xiaoyun from the northern Shanxi province sat through a test prep course for older students. She chose to write under a pseudonym because she took the exam without telling her friends or family.

This is her story.

“The key to good governance is ensuring the people’s well-being. The key to ensuring the people’s well-being is understanding their suffering...”

These lines were part of the classic prose that a group of students in their early 30s recited at 10 p.m. earlier this year in Shuozhou in the northern Shanxi province. They had gathered in the city at a hotel, one floor of which had been converted to house makeshift classrooms for civil service exam cram courses.

Adapted from an adage attributed to the 16th century Ming dynasty statesman Zhang Juzheng, this famous phrase, also quoted by Chinese President Xi Jinping, is often used in the essay section of the civil service exam. I sat reciting the lines with my hands over my ears, eyes closed.

Ten minutes later, our essay teacher, Mr. Bai, picked up the microphone and said: “Next topic.”

We moved on to a question from the 2019 Shanxi provincial civil service exam: “Summarize the following 800-word essay about a successful practice adopted by a particular county.” Mr. Bai explained how best to tackle this question: list out the verbs, organize and summarize, plan the length of each key point, and then write out the answer.

By then, it was nearly 11 p.m., and with no sign of class ending, I had to cancel my taxi bookings several times. When Mr. Bai finally said, “Let’s call it a day,” I grabbed my bag and rushed out.

After four hours of being bombarded with information, I could finally go home and get some rest. My classmates followed me out one after another, each looking exhausted.

That’s how we spent most evenings: studying hard and then working through the day half-asleep. The cram course was split into two components. The first consisted of two months of night classes, while the second involved more than 60 students spending seven days and nights holed up in hotels that doubled as classrooms.

In the second stage, every day started with a different teacher discussing a topic in the morning, followed by a mock test in the afternoon, and then we’d recap and listen to lectures in the evening. When we tuned into online lectures, I joined students in dozens of cities across China all cramming in similar training centers.

Safety net

In 2020, my mother fell ill and my family began pressuring me to get married. That’s when I quit my job in the southern city of Shenzhen, Guangdong province, and decided to go back to my hometown of Taiyuan, the capital of Shanxi province. More than a month later, I traveled to Shuozhou, also in Shanxi, where my boyfriend lives. My boss in Shenzhen told me that I could return any time but I chose not to.

At the time, I was nearly 30 years old and had no means of buying a house in such an expensive city. Hoping to settle down, I decided to find work here in Shanxi.

For the first three months, I worked six days a week from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. as a planner at a health product company. Most employees there were married and often spoke about family issues — I felt like the odd one out.

What’s more, after various deductions, my salary totaled to less than 3,500 yuan, which wasn’t even a third of what I earned in Shenzhen. Once, I was even fined for being late when it snowed heavily. That’s when I decided to quit and start working online from home.

However, my family constantly worried about me. They believed I should get a “real” job, especially since my boyfriend’s family all worked in the public sector. They told me that I could do whatever I wanted after I’d entered the system myself.

To underscore the point, my family mentioned the science fiction writer Liu Cixin who wrote his famous book “The Three-Body Problem” while working at a state-owned power plant. They also told me that in a year or two, I’d be married and might even have a baby. They’d say, if I didn't join the system, who’d pay for my maternity leave?

After that, my boyfriend took me to a coaching center in Shuozhou that helped people prepare for the civil service exam. As I stepped out of the elevator, I saw a red banner with the words: “A year of hard work, a lifetime of happiness.” The corridor walls were plastered with forms listing the dates for exams in teaching, jobs for civilians in the military, and other positions.

My boyfriend pointed to the forms and simply said, “Just pick one.” I chose the civil service exam.

The tuition fee was 42,800 yuan, but you’d get a full refund if you didn’t pass the exam. I thought it was too expensive. But my boyfriend ran the numbers: 40,000 yuan in exchange for financial security for the rest of my life was still worth it. He said that I was smart and that I might even ace the exam on my first try.

I asked the coaching center saleswoman if a cheaper course was available. There was: an evening program that cost 25,800 yuan over 58 days. I asked who the course was designed for. “Middle-aged people who work,” the saleswoman replied.

Though she said “middle-aged,” what she really meant was those already employed, as opposed to students still in or fresh out of college. Like me, they were closer to the age of 35 — the cut-off limit to take the civil service exam.

Back to school

I joined the class on Jan. 1, 2021. It was taught at a budget hotel six kilometers from my home in Shuozhou.

Since it was in a hotel, I imagined classes would involve everyone sitting on a bed watching TV. But when I arrived, I found the whole second floor had been converted for use as classrooms. Each classroom measured around 10 square meters and had five or six desks, a projector, and a whiteboard.

A student liaison officer issued me 10 heavy textbooks. Though there were just two parts to the exam — the administrative aptitude test and the essay — there was a book for each topic covered.

I took the books and sat in a corner of the classroom, overcome with a sense of irony. After graduation, many of my classmates from university in Guangdong passed such exams to work at public institutions. But I went to Shenzhen on my own, where I earned a little more than those back home. When we got together, I’d always pay the bill if I saw that they were a little short. Back then, I never imagined I’d eventually try and follow them down the same path.

My thoughts were interrupted by the arrival of our math teacher. The first class was on division and covered quick calculation methods similar to what I’d been taught in elementary school. But it had been so long since I studied such things that I didn’t understand a word of what the teacher was saying. The other students around me looked just as puzzled.

The teacher nevertheless plowed on, even remarking that our progress was too slow. His demeanor took me straight back to high school, and I began sweating as old fears about math returned. Half an hour later, I was still at a complete loss, and my mind began to wander.

Three hours later, the first class ended and we were already a third of the way through the thick textbook. I’d completely given up on the idea of actually learning anything — at this age, doing so was just asking for trouble.

During the 15-minute break, everyone looked unenthusiastic but we didn’t dare ask the teacher questions, fearing we’d be humiliated.

I made up my mind not to worry about studying but rather just make some friends instead. After that, I began to relax a little.

Iron rice bowl

Only on the third day did all 12 students attend class together. Throughout the cram course, some students were often late, coming to class half an hour after it started at 6:30 p.m. Others were regularly absent altogether.

On most evenings, I sat in class fiddling with my pen, playing on my cellphone, or just staring into space. I spent ages practicing questions, only to find more than half were incorrect. A week later, math class was finally over. I only scored 50 points out of 100 on the quiz, but I felt pretty satisfied.

Next came logic class, and things started to improve. During the break, I began talking with other women in my class, and for me, that was like a small ray of light on the dark road to the exam.

One of them, Wei Hong, sat in front of me. She had the Chinese character for “filial piety” pinned to her right arm, indicating she was mourning the loss of a loved one. In math class, she looked serious as she followed the teacher, always writing and calculating.

She was 31 with a five-year-old child and worked for a local company that was about to go public. My boyfriend said it was a good company with a strict recruitment policy.

When I asked why she wanted to take the civil service exam, she just waved and said: “I don’t have weekends off and the overtime is endless. I'm always on edge.” Her company required employees to make housing fund contributions themselves, and her monthly mortgage repayments left her under a lot of pressure.

Despite having worked there for five or six years, Wei’s salary was still 5,000 yuan, and she received no benefits during her maternity leave, getting only an extra 300 yuan per month after she returned to work.

A classmate of Wei’s in Taiyuan who became a civil servant was granted marriage and maternity leave among other benefits. Though her salary was about the same as Wei’s, her mortgage was only around 200 yuan per month after deducting her and her husband’s housing fund contributions. She also drives a car that costs more than 300,000 yuan, while Wei can barely afford a single extracurricular class for her daughter.

A few months ago, Wei’s father died after she spent a significant amount of money on his treatment. Only allowed to take three days of leave to mourn, she saw the ugly truth in working for private companies. “You still don't understand the benefits of being in the (civil service) system yet,” Wei said. “Women in particular need to have a stable job.”

I tried to comfort her over the loss of her father, but she surprised me by waving her hand again, saying: “It only took six months for my father to go from being diagnosed with liver cancer to passing away. All kinds of reimbursements weren’t enough — that’s why I made the decision to eat from the public bowl.”

The age limit

After logic came my favorite part of the course — speech class. The teacher was witty, and the students became chattier during and after class.

During this time, I got to know a married couple who sat diagonally across from me. The husband, Li Xun, worked in Beijing after university. With no hope of buying a house there, he returned to Shanxi province and originally wanted to settle down in Taiyuan.

After considering his parents, however, he eventually decided to return to his hometown of Shuozhou. He and his wife Wang Xia bought a house and got married last year. Li found a job at an internet company and Wang worked as a copywriter. Their income was only a quarter of what they had earned in the capital.

On a snowy night, the couple gave me a lift home. As we chatted, I asked why they wanted to join the civil service. Looking a little embarrassed, Wang said she quit her job when she got pregnant, but feeling restless, she decided to take the exam with her husband. If she passed, she’d only need to work four days a week and would have more time to take care of their child.

Incidentally, Li had already taken the exam twice but his attempts paled in comparison with a classmate of his in Guangdong who took nine different exams in two years, flying all over and signing up wherever an exam was advertised. Li wasn’t sure how much money his friend had spent on his endeavor, but the friend finally “went ashore” last year.

In speech class, we remarked on the persistence of Li’s friend, but the teacher wasn’t very impressed. He said that a former student of his took the exam every year right up until the age of 35, finally succeeding on his last attempt.

“On average, it takes two years to go ashore,” the teacher said. We heard that our coaching center had sent this teacher to take the real exam, and that he’d scored a considerable 150-160 out of 200. Asked why he didn’t become a civil servant himself, he simply shrugged and joked that the average salary of 4,000 yuan wasn’t enough to support his “multiple girlfriends.” We all laughed.

Not long after, the student liaison officer messaged us out of the blue telling us not to attend class. A week later, when we were asked to move to a new location, Wei Hong told me why: the classrooms on the second floor had been shut down allegedly because a competitor had reported the school for holding gatherings in violation of pandemic prevention measures.

The new classroom was also in a hotel — a large room complete with beds, sofas, a whiteboard, and a television. The desks were packed tightly together.

Since we’d fallen behind schedule, class hours were extended, with lessons now running 7 p.m. to 11 p.m. During classes, the hotpot restaurant downstairs was always busy, filling the classroom with noise and wafts of food from below. One day, the teacher joked that if we wanted to become civil servants, we had to learn to resist temptation.

As Chinese New Year approached, only five or six students came to class each day and no one was in the mood to study. Even the teacher said he was tempted to doze off in class. As such, he never gave us homework because we just didn’t have the time to do it.

Making a difference

The day before Chinese New Year, only me and another woman called Yanan attended class. Yanan was always the last to leave, and went home on the last night bus for high school seniors who were studying late for the national college entrance exam. The fare was only 1 yuan.

The bus stopped near my house, so I decided to join her. She told me that she came from a neighboring county and started registering for various exams immediately after junior year in college. She majored in secretarial administration, where competition was very fierce and she never succeeded. She now worked as a temp at a subdistrict office, but her family wanted her to find a stable job.

“I’m too slow in answering the questions. Last year in the national exam, I had more than 50 questions left,” she told me. When I asked her about her hobbies, she just shook her head.

She told me that when all her classmates took the civil service exam, her family urged her to do the same. However, she had little money and had to take out loans to afford coaching classes. That’s why she waited an extra half an hour before going home — to save a little money.

I tried to reassure her and said that she was still young and had much more time than others. “I hope so,” she replied.

At home for the Chinese New Year, I didn’t even mention to my parents that I was preparing for the civil service exam. After a 10-day break, I returned to the coaching center only to realize that I’d forgotten most of what I had learned.

Back in class, we got a new teacher to teach the essay class, and who was apparently highly regarded throughout Shanxi for helping many students improve their scores. Incidentally, his class was more about copy-editing than writing. What’s more, he allotted some time in every class for us to recite sample composition sentences.

After finishing explaining a prompt about real-life problems, he underscored the need for practicality. “You may have all kinds of dreams, but no matter what post you’re taking the exam for, everyone who passes has the chance to make a difference,” he said. “Some of you will become administrators and service providers for the city one day. All I ask is that you do your best for the people.”

As I listened, I couldn’t help but feel moved.

Yearning to go ashore

On the last day of the two-month course, Wei Hong suggested eating hotpot at the restaurant downstairs to celebrate. One student, Liu Qiang, decided against joining us, saying he had to hurry home. He had a 3-year-old child and lived more than 40 km away from the school.

He attended class every two or three days, but his mind often wandered and he’d ask the teacher where we were in the book every few minutes. He already worked for a public institution but was taking the exam to improve his salary, and hadn’t passed the previous year.

Wang Xia also opted not to go, saying she didn’t eat spicy food. As such, the class of 12 “middle-aged” students went their separate ways.

For the final stretch before the exam, we were divided into different classes according to the positions we’d registered for.

Nearby, I heard a couple of people who recognized one another. They struck up a conversation and discovered that they’d both taken the exam two years ago. Everyone spoke about where it was easier to take the exam, with many people traveling in from surrounding cities, chatting away in their local dialects.

The final day was supposed to be for rest, and the school had organized for a teacher to try and predict the questions we’d get in the exam. The teacher spoke astutely about tricks such as the benefits of keeping your brain and muscles in a state of tension; the high probability of the answer to the last question being option “D”; and recommended that we each buy a geometry ruler set to directly measure out the answers for questions with graphs.

On the day of the exam, my boyfriend and I walked past a temple for the god of exams. He suggested I go in and pray, but I shook my hand in refusal.

But in the end, I didn’t pass the exam.

Later, I contacted some of my old classmates. Wang Xia said her baby was due and that she was also preparing for a separate test as part of the public institution exam. Liu Qiang had finally given up — the commute was too far and he didn’t want to prepare for the exam next year. Wei Hong didn’t pass either and decided to retake the exam again next year.

For those seven days and nights in the cram school, I’ll always remember the classrooms filled with the sound of pages being turned. There were endless problems to solve and more key points than one could ever be expected to remember.

As everyone studied hard, inspirational chants played in the background during the few minutes between classes, the same refrain repeating: “I want to go ashore.”

Liu Qiang, Wang Xia, and Li Xun are pseudonyms.

A version of this article originally appeared in White Night Workshop. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and published with permission.

Translator: David Ball; Editors: Xue Yongle and Apurva.

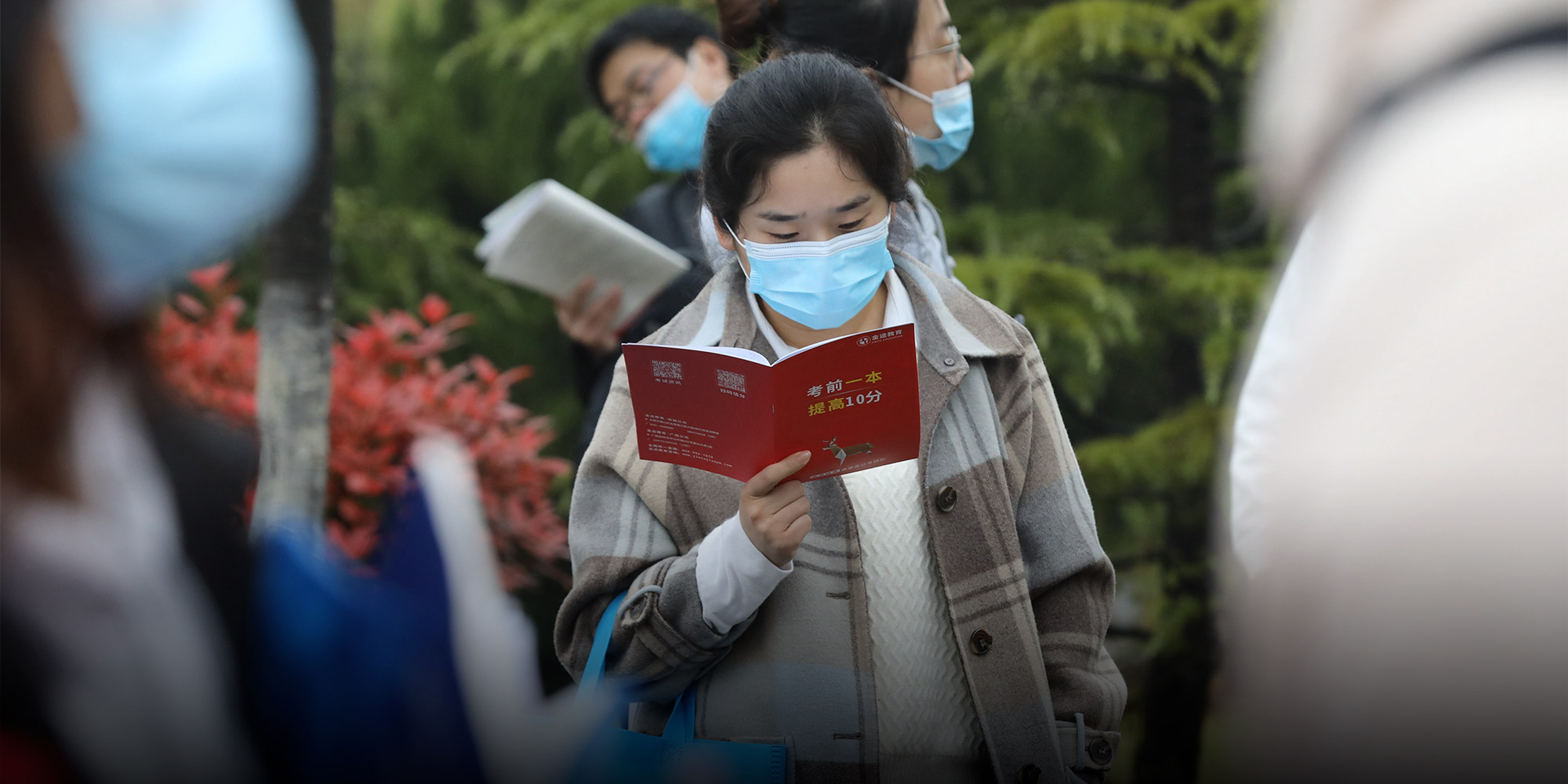

(Header image: A woman looks at her prep materials before entering a national civil service exam site in Hefei, Anhui province, March 27, 2021. Chen Sanhu/People Visual)